Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History reserve the copyright of this article but give permission for parts to be reproduced or published provided Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History are credited in full.

Introduction

In 1987, Ellen Jones, at the age of 89, wrote an article in the Forest of Dean Review called When Charlie Mason led the Miners, describing her experiences of the occupation of Westbury Workhouse during the 1926 miners’ lockout in the Forest of Dean. The occupation was in response to the cutting of relief to the families of locked-out miners in August 1926, leaving them with no means of support. Ellen wrote:

The miners’ leader was Charlie Mason of Brierley, whose daughter is Winifred Foley, the author of A Child in the Forest. I don’t remember if he encouraged us or if we group of women and children of our own free will, went to the Poor Law Institution at Westbury to try and get help for our men.

Some of us went very bravely – I with my two little girls and Jim, a baby in arms. While there we tried to make the best of it. One jolly woman would say. “Never mind girls – cheer up – I can smell bacon and eggs cooking for breakfast.” But no such luck! Just porridge!

The staff did their best for us down there, but we couldn’t cope for long, so we all decided to return home. On the weary walk to Cinderford, we met our husbands coming down to bring us a bit of tea and sugar. The miners’ leader met me and asked if I would take my children into Cinderford Town Hall by the back way, and when I did so, I was met with a roomful of people cheering and clapping, I felt quite a heroine!

This article explores the occupations, protests, and delegations linked to the provision of Poor Law relief for destitute miners and their families in the Forest of Dean. It examines the period beginning with the severe coal trade depression in late 1920, which led to a sharp rise in unemployment, and culminated in the 1926 miners’ lockout.

The Boards of Guardians, who administered each Poor Law Union, held the statutory responsibility to provide relief to the destitute in the form of accommodation in a workhouse or outdoor relief in cash, vouchers or a loan. In the nineteenth century, the destitute could include strikers and their dependents, but after 1900, the law forbade the giving of relief to strikers or locked-out workers, but continued to allow the award of relief to their dependents.

The post-World War One economic depression and industrial strife, which followed, created significant financial strain on the Poor Law system, leading some Poor Law Unions to face bankruptcy due to the overwhelming demand for relief. This article highlights the challenges faced by the Poor Law system during this period of economic hardship and social unrest, as well as the evolving legal restrictions on who could receive public assistance.

The matter of relief became highly controversial during the 1921 and 1926 miners’ lockouts because widespread destitution in the coalfields threatened solidarity. During the protracted struggle of 1926, the determination of miners to resist the temptation to return to work inevitably depended upon their success in feeding themselves and their families. Consequently, the granting or withholding of relief to the families of locked-out men could alter the balance of power between the contending parties in the dispute.

This sometimes led to conflict between members of the Boards of Guardians within each Poor Law union because some were sympathetic to the labour movement and others were hostile. Boards of Guardians, where the majority were keen to support destitute miners and their families, often ran into conflict with the ratepayers who financed the relief and the government, which was keen to end the lockouts.

In some areas, there were allegations that public funds were being used to finance strikes, while in others it was alleged that relief was being deliberately withdrawn to force the men back to work. The administration of poor law relief, therefore, increasingly became a political question as boards of guardians granted or withheld relief based on their views on the merits of the disputes and whether financial help should be provided for the miners and their families.

In the Forest of Dean, this conflict reflected the class dynamics among the main participants. Working-class Guardians like Ellen Hicks, Tom Liddington, Charles Luker, Albert Brookes, Charlie Mason, William Ayland, Harry Morse, Tim Brain and Abraham Booth argued for an interpretation of the Poor Law which could allow them to provide more financial aid to destitute members of their community. On the other hand, Guardians like Lady Mather Jackson and George Rowlinson argued for an interpretation of the Poor Law which reflected their hostility to the mining community.

The decision of the Westbury Board of Guardians in the Forest of Dean to be one of the first Boards in the country to refuse relief to destitute miners’ wives and children in the summer of 1926 during the lockout was highly controversial and was possibly even against the Ministry of Health guidelines. In response, miners’ wives and children occupied the workhouse in protest. The only other Boards of Guardians to take such extreme action in the summer of 1926 were Bolton and Lichfield.

In contrast, the dependents of miners from the majority of Poor Law Unions were provided with relief until the lockout was over in December 1926. The actions of the Westbury Board led to accusations that some of its Guardians were victimising the miners and supporting the colliery owners. This had a significant impact on the course of the lockout in the Forest, where it achieved its aim of driving many miners back to work.

To place the debates in their historical context, it is necessary to provide some background information on the Poor Law itself, the role of the Guardians, the significance of the legal rulings, the changing ways in which the Poor Law was administered and the crisis facing Guardians with rising unemployment and strikes in the 1920s.

The Poor Law Act of 1834

Although Poor Law Unions in one form or another had existed since the late seventeenth century, a new form of Poor Law Union was set up under the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which radically overhauled the system of providing support to the poor.

The Poor Law Act of 1834 was based upon the assumption that relief to the poor should be such that no person receiving relief would be in a more favourable position than the very lowest-paid worker. The principle was that of ‘deterrence’, and a strict distinction was made between the so-called ‘undeserving poor’, usually the able-bodied who were able to work and the ‘deserving poor’, usually sick, disabled or elderly.

The authorities considered that work was generally available to all those willing to seek it and the failure to find work represented a moral failure on the part of the individual rather than a structural problem with the economy or high unemployment. The principle behind the Act was that relief be only offered to ‘the genuinely destitute’ while ‘unemployed malingerers’ would be forced back into the labour market.

Poor Law Unions

Under the Poor Law Act, a national Poor Law Commission was established to oversee the grouping of local parishes into Poor Law Unions, which were financed by local rates. Each Union was centred on a town where a workhouse was situated or planned to be built, and usually covered about a ten-mile radius. There could be 30-40 parishes in each Union, and these sometimes extended across the county boundaries. The new Poor Law was meant to ensure that the poor were housed in workhouses where they were clothed and fed and by the 1860s, all Unions had workhouses. Able-bodied single men would usually be denied outdoor relief, but if the Guardians considered them ‘genuinely destitute’, they could be offered the option of entering the workhouse.

Therefore, workhouse inmates sometimes could include the able-bodied as well as the disabled, the mentally ill, the old, the sick and children who would receive some schooling. However, the conditions in workhouses were designed to deter any but the truly destitute from applying for relief. All workhouse paupers had to carry out work which involved boring, repetitive tasks such as cleaning, picking oakum, breaking stones, cutting timber, etc.[1] Consequently, the working classes hated and feared the workhouse and the stigma associated with pauperism.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the limited space available in workhouses meant that outdoor relief sometimes continued to be a cheaper alternative. Despite efforts to ban outdoor relief, the Guardians continued to offer it as a more cost-effective method of dealing with pauperism.

Board of Guardians

In 1919, central supervision of the Poor Law system was given to the Ministry of Health. However, day-to-day administration at the local level remained the responsibility of elected Boards of Guardians, with the financial burden of relief being shouldered not by the Exchequer but by local ratepayers.

Each Poor Law Union was run by a Board of Guardians which included ex officio members and those elected by ratepayers from their constituent parishes. The Guardians were expected to finance their administration from public funds and local rates. Each civil parish in the Union was represented by at least one Guardian, with those with larger populations or special circumstances having two or more. In the period up to 1894, Guardians were subject to annual elections and could only be male property owners. The main duties of the Board of Guardians were overseeing relief to the poor, assessing applications for relief and setting up and maintaining a workhouse.

The Board of Guardians appointed permanent officers, which included the master and/or matron who were responsible for running the workhouse on a day-to-day basis and the relieving officer who was responsible for evaluating the cases of people applying for relief and allocating funds or authorising entry to the workhouse. There could also be a medical officer, a clerk to the Guardians, a treasurer, a chaplain, and various other officers as deemed necessary.

Over the years, under various Acts, the Board of Guardians became responsible for other duties such as civil registration, sanitation, vaccination, school attendance, and the maintenance of infants separated from their parents.

In 1886, in response to the problem of unemployment, a circular to the Boards of Guardians from the government minister, Joseph Chamberlain, stated that there was a moral responsibility on Boards to provide work for the able-bodied unemployed during times of severe industrial depression. This led to the practice of opening Stone Yards or providing other tedious work. This system was hated by the poor because it usually meant the unemployed working long hours at back-breaking work for a mere pittance.

The Local Government Act 1894

Up to 1894, local parish councillors were elected by ratepayers in a system of weighted voting, with those owning more property having multiple votes. For instance, a cottager had just one vote while a farmer might have six or if he owned his farm, twelve. On the passing of the Local Government Act (1894), the multiple-vote system was abolished and a system of urban and rural districts with elected councils was created.

To be eligible for election or to vote, a person must be on the electoral register and have resided in the district for twelve months before the election. Women, non-ratepayers and those in receipt of Poor Law relief were permitted to vote and to be nominated as councillors. Separate Poor Law elections were limited to urban district councils, while councillors from the newly established rural district councils elected Guardians from among themselves. The term of office of a Guardian was increased to three years. The Boards were permitted to co-opt a chairman, vice-chairman and up to two additional members from outside their own body. The Local Government Act of 1894 provided opportunities for the working class and female candidates to be elected onto the Boards of Guardians and elections were closely fought and increasingly politicised.

Forest of Dean Poor Law Unions

In the years leading up to the early nineteenth century, large parts of the extra-parochial Crown land in the Forest of Dean had been encroached upon by families building rudimentary cabins. However, after the 1831 riots, any long-established squatters who had encroached on Crown land were allowed to remain in their properties and many were given freehold status. As a result, in 1842, the extra-parochial area of the Forest was divided for Poor Law Act purposes into two townships, East Dean and West Dean, in Gloucestershire.

Following the Local Government Act 1894, the township of West Dean became a civil parish in the West Dean Rural District, which also included the civil parishes of English Bicknor, Newland, and Staunton. The paupers in the West Dean Rural District were cared for by the Monmouth Board of Guardians and housed in the Monmouth Workhouse. The Monmouth Guardians were elected from about 30 Parishes in Monmouthshire, the West Dean Rural District Council and the Coleford Urban District.

Likewise, in 1894, East Dean became a civil parish in the East Dean Rural District, which included the 10 other Gloucestershire civil parishes and was grouped into the Westbury-on-Severn Poor Law Union.[2] The paupers in the East Dean Rural District were cared for by the Westbury Board of Guardians and housed in the Westbury Workhouse. The Board of Guardians were elected from East Dean Rural District Council and the residents of the Urban Districts of Awre, Newnham, and Westbury (despite being classified as urban, these districts were mainly rural).

In the case of the Westbury Board, all the Guardians were elected from parishes in Gloucestershire, but some of these were from communities surrounding the mining areas whose primary industry was agriculture. There were approximately 35 Guardians on the Westbury Board, although not all of them could attend every meeting.

In addition to the two main Poor Law Unions impacting the Forest of Dean, there were the Chepstow and Ross Unions. The Chepstow Board of Guardians were responsible for the workhouse in Chepstow, which was in Monmouthshire but covered several parishes in the West of the Forest of Dean, including Hewesfield, St Briavels, Aylburton, Woolaston and Lydney Rural District, as well as the 35 parishes in and around Chepstow. Similarly, the Ross Board of Guardians were responsible for the workhouse in Ross, which was in Herefordshire but covered the Ruardean parish in the north of the Forest of Dean as well as the 28 parishes in and around Ross.

The various local authority bodies were responsible for collecting the rates and passing on a percentage to their Poor Law Unions. However, the wealth of each Poor Law Union differed considerably depending on the rateable value of the properties. The largest town in the Westbury Poor Law Union was Cinderford, where 80 per cent of the male adult population worked in the mines and where the housing stock was poor with low rateable value. Cinderford was part of East Dean Rural District. The highest proportion of the rates was paid by the colliery companies that owned the many mines surrounding the town. The amount of rates the colliery owners paid was based on their annual production and so, during periods of low production or strikes, the rateable value would fall even further.

The significant conclusion that can be drawn from the organisation of Poor Law Relief in the Forest of Dean is that for Monmouth, Ross and Chepstow Poor Law Unions, most of the Guardians were elected from parishes outside of the Forest of Dean mining areas. Consequently, these four Boards were dominated by members who were elected from rural areas and usually chaired by Tory members of the establishment, sometimes from aristocratic backgrounds. Most of these Guardians would have little understanding of or sympathy with the concerns of the Forest of Dean mining community.

In the case of Westbury, most of the Guardians were made up of farmers, employers, shopkeepers and business people and some of them were from the rural parishes surrounding the mining area, which was concentrated around the town of Cinderford.

Liberals and the Guardians

In 1892, Charles Dilke was returned to parliament as a Liberal member for the Forest of Dean. Dilke became a popular MP and an independent thinker, ready to defy the party whip on labour issues in support of the Forest miners. He soon built up a close relationship with members of the mining community and their organisations. This helped to consolidate the Liberal consensus within the mining community in the Forest to Dean. Dominant Liberals within the mining community at this time included:

- Sidney Elsom, President of the Forest of Dean Free Miners Association.

- George Rowlinson, the agent for the Forest of Dean Miners Association (FDMA)

- Martin Perkins, a miner, and the President of the FDMA.[3]

- Richard Baker, a miner and a long-term activist within the FDMA.

All these men were supporters of the more radical wing of the Liberal Party. They worked closely with Dilke and other Liberals to challenge the influence of the Tory Party and their aristocratic representatives on local authority bodies, including the Boards of Guardians and sought to represent the interests of the working classes. Rowlinson was initially elected to the Westbury Board in 1887.

In April 1893, Sidney Elsom was elected to the Monmouth Board of Guardians representing West Dean, polling the highest vote (767 votes) and beating local colliery owner Thomas Deakin (597 votes).[4] He went on to be elected chairman of the Board in 1902, a position he held until just before he died in 1919. Elsom was fond of attacking the aristocracy:

There might have been some who labelled the miners, and men like them, as the residuum, the dregs, the scum but the most striking distinction between ourselves and our ‘noble’ alumniators is this – we have to toil day after day, year after year, work hard, live hard, and still remain poor, while they, as a rule, spend a life of idleness.[5]

Elsom’s election represented a shift in the political landscape in the Forest and provided an opportunity for ‘working men’ to have a voice. William Ayland, who was a haulier and general labourer, was elected in 1893, representing Westbury Urban District Council on the Westbury Board along with several other ‘working men’.[6] The Gloucester Journal obituary of Ayland in 1934 argues:

He was a guardian of the poor and not of the Poor Law. His intimate knowledge of the entire population of poor folk would influence this. Nobody got any relief unless they applied, but doubtless many applications were due to William’s prompting.[7]

In 1893, Perkins, an East Dean Rural District councillor, was elected to the Westbury Board of Guardians, remaining in that role until 1895. Other working-class members who were successful in being elected to the Westbury Board in 1893 were Richard Baker, John Watkins, John Beddis and Fred MacAvoy. In 1895, George Rowlinson was elected as a councillor to East Dean Rural District Council and then to the Westbury Board of Guardians. Rowlinson continued in his role as a Board member, becoming Vice-chair in 1917 and chair in 1920.

These men were very much in the minority on the Board and would encounter deep vested interests when attempting to make any changes or challenge the authority of the ruling elites. The clerk, who worked for the Westbury Board, was Maurice Carter. Roger Deeks has pointed out that:

Carter was the son of a solicitor and nephew of Richard Carter, Mayor of Gloucester. His family had a long involvement in the execution of the Poor Law. He came to Newnham on Severn to practise law when he was 22 years of age, in 1848. Two years later, he was appointed Clerk to the Westbury on Severn Board of Guardians, responsible for the Poor Law and managing the Westbury workhouse, a post he held until 1903. In parallel, he was appointed Clerk to the Newnham Justices in 1863, a post he held for 42 years, and in 1868, the post of Coroner he held for 39 years. Carter had a hugely influential position over life and death in the Forest of Dean, particularly for the old, sick, disabled and unemployed.[8]

Merthyr Tydfil Judgment

As a result of a legal ruling made in 1900, called the Merthyr Tydfil Judgment, Guardians were not allowed to grant relief to destitute, able-bodied men (strikers, locked-out workers or the unemployed) if work was available to them.[9]

The ruling followed a protest by one of the largest ratepayers in Merthyr, the Powell-Dyffryn Company, complaining that during the South Wales Miners’ strike of 1898, the Merthyr Guardians granted relief to strikers. The judgment of the Court of Appeal in Attorney-General v. Merthyr Tydfil Guardians (1900) set the precedent:

Where the applicant for relief is able-bodied and physically capable of work, the grant of relief to him is unlawful if work is available for him, or he is thrown on the Guardians through his own act or consent, and penalties are provided by law in case of failure to support dependents, though the Guardians may lawfully relieve such dependents if they are in fact destitute.

As a result of the ruling, striking or locked-out miners were now considered by the authorities not to be destitute because they were deemed to have refused work. However, the ruling stated Guardians were required to relieve the wives, children and widowed mothers of the striking men if they were destitute, but not the men themselves.

The allocation of relief to the wives and children of men involved in an industrial dispute meant the relief would also be shared with the man. Since the Boards offered different amounts of relief, the degree to which the families of locked-out miners were supported varied from district to district. However, the ruling severely impacted the well-being of single unemployed men.

The ruling over whether strikers, locked-out workers or the unemployed were refusing work available was interpreted differently by different Boards. The ruling allowed the relief of a man involved in an industrial dispute if they became so reduced by want and destitution that they were incapable of work, in which case they could be admitted to the workhouse. If this were the case, a doctor may be asked to provide a medical certificate. However, incapacity to work was interpreted differently by different Boards and doctors.

The Labour Party

From about 1908, branches of socialist organisations such as the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the British Socialist Party were formed in the Forest of Dean and started to challenge the influence of the Liberal Party, arguing for Labour candidates in local and national elections.

In 1912, Ellen Hicks, a member of the ILP, was elected as a Monmouth Poor Law Guardian for the Coleford Urban District Council. In 1917, Tom Liddington, also a member of the ILP, was elected to represent Coleford on the Monmouth Board of Guardians.[10]

During the First World War, a small number of younger men had gained positions on the FDMA Executive. They argued against the policies of moderation and conciliation pursued by Rowlinson, who, in the period before the war, opposed attempts by the FDMA to affiliate with the Labour Party. Rowlinson was finally voted out of office by the Forest of Dean miners in early 1918 over his hostility to the Labour Party, his support for the conscription of miners and his failure to support his members during industrial disputes.[11] He was replaced by Herbert Booth, a young socialist miner from Nottinghamshire. Rowlinson was hostile to the newly formed Labour Party and the new Executive of the FDMA, which was made up of younger men.

At the end of May 1918, James Wignall, an official of the Dockers Union from Swansea, was adopted as the Forest of Dean Labour candidate at a meeting attended by over 70 delegates and with the full support of the FDMA. In November 1918, Wignall defeated the Liberal candidate, Sir Harry Webb and became the first Forest of Dean Labour MP.

In about 1920, Charles Luker was elected as a Labour member on West Dean Rural District Council and then onto the Monmouth Board of Guardians. Luker worked at Princess Royal colliery and was on the FDMA Executive.[12] This meant that by 1921 there were three socialists on the Monmouth Board from the Forest of Dean: Luker, Hicks and Liddington.

In 1919, Frank Ashmead, an ex-miner with a history of long-term activism within the FDMA and now working for the cooperative bakery, was elected to the Westbury Board.[13] In 1920, Rowlinson was elected chair of the Westbury Board but sat as a Liberal and later as an independent, still refusing to join the Labour Party and becoming increasingly alienated from the mining community.

World War One exacerbated the divergence of class interests in British society and eroded the prevailing pre-war liberal notions of a classless society and a commonality of interest among those who sought to represent the interests of the working class. In 1919 and 1920, an upsurge in working-class militancy spread across the nation.

However, at the end of 1920, there were clear signs of a crisis ahead as the average price of export coal fell from £4 to about £2 a ton and unemployment in the coal industry rose to 20 per cent.[14] The crisis spread to other industries, and in 1921, Britain entered a period of severe economic depression. The unemployment rate among all workers climbed to 23.4% by May 1921, reaching a figure of 2,171,000 by June 1921.[15] From there, it never fully recovered, remaining over 10% in almost every month of the 1920s.

The collapse of the post-war boom reflected Britain’s decline as the ‘Workshop of the World’. The industries on which Britain’s export trade was based suffered the most and so the steam coal regions, which exported their coal, were hit hard.[16] This created an uneven distribution of mass unemployment and had two consequences. One was the sharp geographical polarisation of employment patterns. The other significant feature was the very high level of long-term (i.e. more than six months) unemployment.

As a result, in the 1920s, the Poor Law Unions entered a state of crisis as the demands on the Guardians increased with a corresponding increase in the pressure on the rating system to finance its obligations and this led to conflict between the interests of the poor and those of the wealthier ratepayers. The problem arose because of the unprecedented rise in the numbers of those receiving Poor Relief due to unemployment, poverty and industrial unrest, particularly in the coal mining districts. Between 1914 and 1922, the number relieved in England and Wales was as follows:[17]

| Date | Number Relieved |

| August 1914 | 619,000 |

| November 1918 | 450,000 |

| July 1921: | 1,363,121 |

| March 1922 | 1,490,996 |

| September 1922 | 2,500,000 |

In addition, up to 1920, relief was rarely given to able-bodied men, but after 1920, the traditional safeguards against providing unconditional relief to the unemployed by insisting on a place in the workhouse and/or being engaged in menial work collapsed. The flood of applications received by the Guardians in the 1920s was not from traditional paupers, the sick or disabled, but from able-bodied unemployed men with families to support.

The stigma attached to pauperism began to collapse and increasing numbers of destitute unemployed men and women sought relief from the Guardians. As the number claiming relief rose, it became apparent that all of these could not all be housed in the workhouses. In addition, for some, it was also no longer politically acceptable to refuse outdoor relief to the unemployed, particularly as many were World War One veterans. Consequently, it became much more common to support families with outdoor relief. In 1920, there were never less than a million recipients of outdoor relief, and of these, one in four were able-bodied.

At the same time, the 1920s saw significant changes in the composition of local Boards in numerous industrial towns and cities. Traditionally dominated by representatives of the property-owning classes, some Boards experienced a shift in their composition as the influence of the labour movement grew. In many cases, representatives of the property-owning classes lost, or nearly lost, their predominance.

Labour movement-dominated Boards had a majority of Labour Party members, some of whom were also trade union members or officials and often sympathetic to workers on strike. Boards of Guardians, where Labour members held a majority, typically managed their duties toward the poor with sympathy and even generosity within the confines of the law, but sometimes overlooked the interests of local ratepayers.

However, the Guardians were still expected to operate within guidelines laid down by the Ministry of Health, but how each Board responded to the crisis varied considerably from district to district. Some boards, particularly those with a labour movement majority, abandoned any attempt to set in place menial work for the able-bodied unemployed and argued that the burden of unemployment should be borne nationally and not thrust upon poor districts with high levels of unemployment and lower income from rates.

The Insurance Act of 1920

To understand the dilemma of the Poor Law Unions in the 1920s, it is necessary to look at the degree to which the system of insurance for the unemployed had developed by this time, and how this had changed social attitudes towards the able-bodied poor.

From November 1920, the new Unemployment Insurance Act covered 12 million workers and provided unemployment benefits to some of those without work. Under the Act, an employee paid 4 pennies (d) a week, the employer paid 4d and the State paid 2d. In return, the unemployed insured man could receive 15 shillings (s) a week (2s 6d a day) and the unemployed insured woman 12s a week for fifteen weeks a year. However, there were stringent conditions:

- The claimant was only entitled to one week of payment for every six weeks of contributions. This meant that claimants could run out of benefit entitlement.

- The claimant was required to be out of work for more than three days, but this was later increased to six days. This meant it was difficult for part-time or temporary workers to meet the qualifying period.

- If these conditions were not met, the unemployed could ask the Guardians for means-tested relief and given the high level of unemployment among both insured and uninsured workers, this became increasingly common.

The role of unemployment benefits was originally intended to supplement the resources of workers during brief spells out of work. They were not designed to support the chronically unemployed. Soon after unemployment insurance coverage was extended, mass unemployment set in. When the 1920 Unemployment Insurance Act came into effect, the unemployment rate was 3.7% in the insured industries; barely six months later, in June 1921, it was 22.4%.[18]

The Depression of 1921 set the tone for the inter-war years, when the average rate of unemployment was 14 per cent of the insured workforce.[19] The persistence of high levels of chronic unemployment undermined the basic principle behind the 1920 Act, which assumed that claimants received unemployment benefits as a right but for a limited period, having previously paid contributions towards their benefits.

The Poplar Rates Rebellion

The inequalities of the rating system of local government finance became starkly apparent in the 1920s with the rise of mass unemployment, particularly in mining areas. Those councils with the highest unemployment usually had the lowest rateable values. Consequently, they were under pressure to raise the rates in response to increasing social distress. This was a key issue underlying the struggles of some Labour councils, which brought them into legal conflict with the government in this period, most famously in the London borough of Poplar in 1921.

The Poplar Rates rebellion in East London in 1921 was a product of the increasing economic pressure on local authorities and Boards of Guardians in poor communities with high unemployment, leading to high local rates to fund services and the Poor Law. In early 1921, the Labour-controlled council and the Guardians in Poplar agreed to avoid cutting services or increasing rates by refusing to collect and pay the ‘precept rate’ that was required to give to the London County Council and other cross-London bodies. The councillors knew this was illegal but believed that defying an unfair funding system was better than cutting much-needed services, including relief for the unemployed, or increasing rates to unaffordable levels.

On 29 July 1921, five thousand people marched from Poplar to support their rebel councillors at the High Court on the Strand. The judge told the councillors that they must pay the precepts or go to prison indefinitely for contempt of court. The councillors refused to collect the precepts, and at the start of September 1921, the sheriff arrested thirty of them, taking five women councillors to Holloway Prison and twenty-five men to Brixton Prison.

The councillors continued their campaign and even held official council meetings in prison. Supporters held daily demonstrations while Stepney and Bethnal Green councils also voted to refuse to pay the precepts. In mid-October, the government conceded, arranged for the councillors’ release, and quickly passed a law reforming London’s local government funding, making rich boroughs contribute more, and sharing the cost of maintaining the poor.

The Poplar rebellion had very clearly demonstrated that there were no effective legal remedies to force local councils to obey the law. It was difficult for the government to simply take over the running of such councils, and the only recourse was to surcharge the councillors individually to try and force them to back down, and failing that, to send them to prison. In Poplar, this only made martyrs of the councillors and amplified the significance of their protest, to the discomfort of both the government and the national leadership of the Labour Party.

In some Poor Law Unions where Guardians from the labour movement were in the majority, the granting of unconditional and relatively generous relief to the unemployed during this period was motivated by more than a natural desire to defend the living standards of working-class families. There emerged a general strategy aimed at forcing central government to accept responsibility for the relief of the unemployed. Militant and ideologically motivated defiance of central government policy in matters of Poor Law administration spread to neighbouring East End Unions and then into the mining districts, where labour movement members often dominated the Boards of Guardians.

The Poplar Rates Protest gave rise to what became known as ‘Poplarism’ – a polemical epithet used by Conservatives to refer to high-spending, left-wing Poor Law Guardians in the 1920s. Poplarism represented a small but significant change in the balance of institutional power at the local level which would have a significant impact on whole communities during the 1921 and 1926 miners’ lockouts.

1921 Lockout

In 1921, the response from the government and the owners to the depression in the coal trade was to allow ruthless competition to take its toll. They argued they had no alternative but to resolve the economic crisis in the coal industry by radically reducing labour costs, which, in the Forest of Dean, translated into wage cuts of up to 50 per cent. The miners refused to go to work under these new terms and downed tools. As a result, on 31 March 1921, one million British miners were locked out of their pits, including many war veterans and over 6,000 miners from the Forest of Dean.[20]

Most mining families had little savings, particularly as many had only been working part-time for several months due to the depression, and so within a week, some families had run out of money and food. In many mining districts, local mining associations advised their members to claim outdoor relief, and consequently, in most districts, relief was awarded to miners’ families (wives, children and mothers) with the sanction of the Ministry of Health.

The relief was usually offered in the form of a loan to the dependents of locked-out miners and typical amounts were 15s for a wife and 3s for each child. Issuing relief as a loan rather than a grant was one way the Guardians could reduce their expenditure. Some of the Boards, in particular those which had a majority of Guardians who were members of the labour movement, paid out more.

However, in the Forest of Dean, the FDMA was at a disadvantage because it felt there was little hope that the local Boards of Guardians, which were dominated by Tory members, would be sympathetic to hundreds of miners and their families claiming outdoor relief. Consequently, the FDMA arranged for food vouchers to be issued as loans from the local Cooperative Societies and traders. But, before the vouchers could be issued, some families turned to the Guardians and asked for relief.

Monmouth

However, since the strike pay had run out after three weeks and there was a delay in issuing the vouchers, some colliers, including some who were ex-soldiers, and their families presented themselves for relief at the meeting of the Monmouth Board of Guardians on 29 April, arguing they were on the point of starvation. One of the Guardians, T.W. King, said:

If this is a land fit for heroes to live in, are we going to put men in the workhouse after they went out and fought for us?[20a]

Fortunately for the applicants with families, two of the Guardians, Charles Luker, a locked-out miner, and Tom Liddington, a Labour councillor, argued for a temporary loan. As a result, several families were lent 15s per wife and 2s 6d for each child to help them out until they were issued with traders’ coupons. However, the voucher system had an unintended effect: once vouchers were issued, the Guardians could argue that families were no longer destitute and therefore not their responsibility.

On 21 May, the clerk of Monmouth Board of Guardians informed the Ministry of Health that the Board had granted relief in 12 cases to the wives and children of locked-out miners in the form of food vouchers and a loan to the amount of 15s for a wife and 2s 6d for a child. [20b]There are no other recorded cases of domiciliary relief being offered to the families of miners by the Monmouth Board during the 1921 lockout. At the next meeting of the Monmouth Board on 27 May, Mr Alford of Coleford said:

that but for the coupon system, they would have had a hundred miners that day from the Dean Forest area of the union applying to the guardians for relief.[20c]

A letter from the clerk to Mathers dated 28 May stated:

Several applications for relief from able-bodied men came before the Board, but relief was practically refused unless the men themselves came into the workhouse, and as far as I could gather yesterday, none of them would accept this and therefore no out-relief was given. [20d]

Westbury

Up to 1921, the chair of the Westbury Board was Sir Russell Kerr, a local aristocrat and staunch Conservative. In March 1921, Kerr resigned and was replaced by George Rowlinson, the ex-FDMA agent, who sat as an independent. William Ayland and Frank Ashmead were now Labour members. Other Labour members were Tim Brain and Abraham Booth.

Brain was employed as a deputy at Cannop Colliery (which is a colliery official charged with the supervision of safety, the ventilation of the workings, the inspection of timber work, etc). He was elected as a Labour councillor on East Dean District Council in 1919 and, at the same time, he was elected as a member of the Westbury Board of Guardians. In 1922, he was elected as a County Councillor for Drybrook when he was described by the Dean Forest Mercury as belonging to “the extreme section of the Labour Party”.[24] .

Booth worked as an insurance agent for a Friendly Society and was the son of a coal miner from Yorkshire. His daughter was married to a coal miner from Cinderford. In 1919, he was elected as a Labour member of East Dean Rural District Council and then onto the Westbury Board of Guardians. The remaining 30-odd members were mainly from middle or upper-class backgrounds.

There is no record of the Westbury, Chepstow or Ross Boards issuing relief to the families of locked-out miners during the 1921 lockout.

Unemployment

The lockout ended after 12 weeks when, on Monday 27 June, the MFGB advised the men to return to work and accept the reduction in pay. Some had to wait several weeks before they could return, while repairs were carried out to pits damaged by flooding and rock falls. On Monday 4 July, at one Labour Exchange alone, Lydbrook in the Forest of Dean, over 300 men registered as unemployed, with more registering the following day.[25] However, the government announced that men who were unemployed because of damage to their pits due to the lockout could not receive unemployment benefits.

At a meeting of the Westbury Board of Guardians on 28 June 1921, Mr Long, the Relieving Officer, reported that he had recently been before the Auditor, who had impressed upon him that no relief could legally be given to families where the collier husband was out of work because of the lockout.[26]

The FDMA agent Herbert Booth spent much of his time over the summer months supporting his members in their attempt to make benefit claims.[27] In the summer of 1921, there were 50,000 unemployed miners in South Wales out of a total of 250,000. Many Forest of Dean miners who were working in South Wales returned home, swelling the ranks of the unemployed in the Forest. Despite this, the population of the Forest of Dean fell after 1921 as people moved away to get work in other areas.[28]

The Forest of Dean miners also had to face another consequence of the lockout, which had left the FDMA massively in debt, owing over £27,000 in credit coupons to local retailers. This was exacerbated by a loss of membership from about 7000 to 1500.

Outdoor Relief

An additional burden on the unemployed resulted from the government’s decision to extend the qualifying time before providing unemployment benefits from three to six days. The only alternative for people who were not entitled to unemployment benefits was means-tested outdoor relief, under the Poor Law. Claiming Poor Law relief would have been very humiliating for unemployed miners, some of whom were World War One veterans. In any case, relief could still be refused by the relieving officer, who could claim the rules stated they could not offer relief to those who were unemployed because of the damage to their pits due to the lockout. In one case at Westbury, Booth pleaded with the Guardians to provide boots for children so they could attend school, but this was also refused. However, the Monmouth Board of Guardians agreed to offer relief to those in extreme distress as a loan.[29]

As the depression deepened, some miners were permanently laid off, and others were offered only two or three days of work a week. Harry Toomer described the system:

You had to listen for the hooter every night and every pit had its hooter and everybody knew their own pit’s sound of hooter. And if there was no work the next day, they would give loud blasts on the hooter for minutes on end – no work tomorrow … that was called a play day.[30]

If they were out of work for more than six days, they were able to claim benefits. However, a miner who worked, for instance, only six days in six weeks may not have been entitled to a single penny of benefit, simply because he could not show the necessary waiting period of six days of unemployment.[31]

Others who were unemployed had exhausted their benefit under the rules of the Act, which only allowed one week of payment for every six weeks of contributions. Other unemployed applicants were refused benefits because they were not considered to be genuinely seeking work, not formerly insurable or otherwise not able to comply with the conditions for receiving benefits. Some presented themselves at Westbury and Monmouth Boards of Guardians asking for relief, but, as a rule, the most the Guardians could offer was a one-off temporary loan.[32]

Unemployment among insured workers in the Forest of Dean, 1920-1921 and the total population in 1921

| Date | Cinderford Area | Coleford Area | Lydney Area | Newnham Area | Total | |

| September 1920[33] | Total for Cinderford, Coleford and Lydney | 29 | ||||

| January 1921[34] | 107 | 66 | 264 | 26 | 463 | |

| November 1921[35] | 2233 | 473 | 999 | 142 | 3847 | |

| Total Population in 1921[36] | 20,494 | 17,431 | 9,842 | 4,029 | 51,796 | |

The figures mainly refer to those in receipt of unemployment benefits and, therefore, are insured workers who have met the qualifying conditions. Some of these may have been working part-time but still were able to claim benefits.[37] The figures do not include most women (uninsured), children, the elderly, the disabled, striking miners, miners unemployed because of an industrial dispute and uninsured unemployed workers. Unemployment among miners was comparatively low in August and September because, when the miners returned to work after the lockout, coal was needed to replenish stocks. However, the demand for coal was only temporary and, as the depression deepened, unemployment grew until 1924, when there was a temporary rise in demand for coal.

The Guardians struggled to cope with the demand for relief. The chair of the Monmouth Board, aristocrat Lady Mather Jackson, had little idea of the distress existing in the Forest of Dean. Mather-Jackson was the wife of Sir Henry Mather-Jackson, 3rd Baronet, who held extensive business interests in mining and railway infrastructure.[38]

However, some Board members were shocked at the state of destitution of some of the miners claiming relief. Most believed they should not let women and children starve. Although some, such as William Burdess, the under manager at Princess Royal colliery, were less sympathetic and relief was sometimes refused to miners who had been involved in the lockout. Among the twenty-five Guardians on the Monmouth Board were Forest of Dean Labour Party representatives Charles Luker, Tom Liddington and Ellen Hicks, who spoke up on behalf of the miners by arguing for a system of loans.

Photo of William Burdess (Credit Dean Heritage Centre)

At Westbury, Rowlinson argued that the Board received no money from the central government and all the money available had to be raised from the local rates. However, other Guardians in other districts had successfully applied for loans from the Ministry of Health or arranged overdrafts with their bank. At Westbury, the Board agreed to only offer relief for two weeks at a time and as a loan for those in extreme distress. Otherwise, applicants could be offered a place in the workhouse.

In November 1921, a Guardian on the Westbury Board argued that it would be unfair to offer relief to the unemployed while many local miners were working two or three days of work a week and earning only 25s a week. In response, a miner who had just returned from South Wales (see the table below) responded:

There are thousands who are living in a state of privation, although they are at work, and if they would give me only two or three shifts a week at the colliery, I shall have to share their fate. As it is, I am absolutely destitute, without the assistance I have had, I am not going to see my wife and children starve. They can put me behind bars before that shall happen, and that is a terrible thing for a man to say who has always led a straight life and who has references from South Wales of many years standing.[39] He went on to explain that he was planning to walk back to South Wales to pursue his claim for unemployment benefits.

Some cases heard before the Monmouth and Westbury Board in September 1921.

| Board of Guardians | Applicant | Dependents | Unemployment Benefit | Decision |

| Monmouth.[40] | Unemployed miner. | Wife and six children. | Claim for unemployment benefit rejected. | A loan of 25s a week. |

| Monmouth.[41] | Miner earning 30s a week part-time. | Wife and six children. | Claim for unemployment benefit rejected. | A loan of 6s a week. |

| Westbury.[42] | Unemployed miner. | Wife and six children. | In receipt of 15s a week unemployment benefit. | A loan of 20s a week. |

| Westbury.[43] | Destitute single man who worked at Lightmoor before the lockout. | None. | Claim for unemployment benefit rejected. | Offered a place in the workhouse. |

| Westbury.[44] | Unemployed miner from South Wales with family living in the Forest. | Wife and two children. | Claim for unemployment benefit rejected. | A loan of 25s a week. |

The Coleford and West Dean Unemployed Committee

In September 1921, a committee of the unemployed was formed in West Dean to provide solidarity and support for those forced into poverty. The Coleford and West Dean Unemployed Committee’s main objectives were to support the unemployed in obtaining unemployment benefits or relief at the Board of Guardians and to lobby the authorities for work schemes for the unemployed with rates of pay based on trade Union conditions of work.

Two of the main organisers of the committee were Tom Liddington and William Hoare, a miner from Bream. Hoare was among the most vocal in the campaigns against poverty and unemployment, as the broader community rallied around to provide support.[45]

Similar unemployed committees had sprung up throughout the country, and many were affiliated to the National Unemployed Workers Movement, which was set up by the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). On Tuesday 13 September 1921, a demonstration of 3000 men, women and children marched with banners from the Market Square to the workhouse in Gloucester, demanding work or maintenance. As a result, Gloucester Council, with the aid of a grant from central government, provided relief work, such as stone breaking and road works, for about 400 men. They were offered a basic maintenance allowance of 15s for a single adult, 30s for married couples, 5s for each of the first four children and 2s. 6d. for each remaining child.[46]

In September, the police baton-charged marches of the unemployed in Bristol and other major cities and this was repeated at Trafalgar Square in October, resulting in the death of one of the demonstrators.[47]

On Saturday 1 October, a public meeting was organised by the Coleford and West Dean Unemployed Committee in Coleford. The main speakers were Tom Liddington, Reverend John Putterill and Charles Drake. Putterill was ordained as a deacon and now worked as a curate at Coleford. He had worked in the East End of London and, unusually for an Anglican curate, he was a supporter of the communist cause. His speech mixed religious metaphors with communist idealism:

The capitalist system depended on unemployment and those who owned made slaves of those that did not. The position of the workers of this country was that of the Israelites in Egypt – they were absolute slaves – and if they wanted their freedom, they would fight for it.

Charles Drake, a long-standing Liberal councillor on Coleford Urban Council, put forward the following resolution, which was passed unanimously:

This meeting of the unemployed men in Coleford and West Dean calls upon the local authority to bring pressure to bear on the government to introduce schemes of a socially useful character to meet the needs of the situation, the costs to be defrayed by grants from the National Exchequer and not to fall upon local rates.[48]

The following Thursday, 6 October, a delegation of unemployed miners and quarry workers lobbied the West Dean Rural District Council to introduce work schemes for the unemployed. William Hoare, the chairman of the deputation, said the unemployed of the district would prefer relief in the form of work and wages rather than depend on unemployment benefit of 15s a week or relief from the Guardians, which could lead them into semi-starvation. The council responded positively and committed itself to endeavouring to do everything in its power to gain government funding for work schemes.

On Friday 14 October, Hoare led another deputation of unemployed miners from West Dean to place demands in front of the Monmouth Board of Guardians, which was chaired by Lady Mather Jackson. The deputation had to walk from Coleford and, as a result, was late. At first, the Board were reluctant to see them but the Labour Party members of the Board, Liddington, Luker and Hicks, argued that it would be a wasted journey for hungry men if they were refused an opportunity to present their case. Hicks who lived in Coleford informed the meeting that she had:

Seen men walking about hungry. There are men in the district who do have not enough to eat.[49]

Liddington said the men could not wait for another month for the next meeting and in the end, the Board agreed to hear the deputation’s representatives. Hoare spoke on behalf of the men, arguing they needed adequate maintenance until the government could implement its work schemes and said:

Are you aware that while the grass is growing the horse is starving? … they had been forced to come there to seek maintenance till such time as schemes were put into operation. They were unemployed through no fault of their own – they considered the present situation was due to the utter breakdown of the capitalist system.[50]

Hoare said maintenance should be a living wage and they said they would take any work provided it was paid at trade union rates.[51] The Board members responded by arguing that the wage rates would be set nationally and would be considerably below trade union rates. Some of the miners said they would rather starve than ask for relief. In the end, the Board passed a motion urging the government to fund a scheme repairing roads and developing waterworks in the West Dean area. They added that relief would be awarded at the usual rate and according to merit. A member of the deputation ended the discussion by saying, “We want work, we don’t want doles”. As a result of the deputation, the Board of Guardians passed the following resolution:

That the Monmouth Board of Guardians calls the attention of the Government to the serious amount of unemployment existing in the West Dean and Coleford Districts of this Union, and urge the opening up of works of Public Utility, such as a Joint Water Scheme, and the making of roads for the West Dean Rural, and Coleford Urban District Councils.

It was further resolved that copies of this Resolution be sent to the Prime Minister, the Ministry of Health, and the Local Members of Parliament.

On 15 November, Wignall joined a deputation from East and West Dean District Councils and Coleford Urban Council in a visit to London to lobby the relevant government departments to establish work schemes.[52] On 9 December 1921, the Dean Forest Mercury reported that Sir Percival Marling had complained about the sight of unemployed ex-servicemen hanging around the towns and villages of Gloucestershire. He suggested that the government should introduce work schemes for the unemployed to get them off the street.[53] Discussions on a variety of schemes for the unemployed in the Forest of Dean took place over the next two years, but none were implemented at this time.

The Government Responds

During 1921 and 1922, it became apparent that many men had not achieved the necessary entitlement to claim unemployment benefit, causing more destitution. Relief money was raised through the rates and the lockout meant that the collection of rates was hampered by the level of poverty in the community. Consequently, as the demand for relief grew, more Boards of Guardians had to apply to banks for loans. In November 1921, the Ministry of Health set up a committee to consider applications for loans from those Boards of Guardians that were so overwhelmed by applications for relief that they were unable to perform their statutory duties.

In addition, successive governments in the 1920s were obliged to introduce Extended or Transitional Benefits to allow insured workers who had exhausted their right to unemployment benefit to continue drawing benefits. The political imperative was that insured workers (often male, skilled and unionised) could not be reduced to pauperism without incurring the threat of political unrest. There were over twenty amendments to the insurance scheme to this effect in the 1920s, such that at any time after 1921, over half those drawing benefits were not qualified under the 1920 Act.

For instance, in April 1922, the government introduced an Act to allow for the payment of uncovenanted benefits for an extra period of up to five weeks at a time for those who did not qualify. The Act also introduced the concept of a gap, which meant that the unemployed would be without benefits for a gap of five weeks before being provided with benefits for another five weeks. However, this still meant that many of the unemployed were required to apply to the Guardians for relief every five weeks. The gap policy was in operation until July 1923.

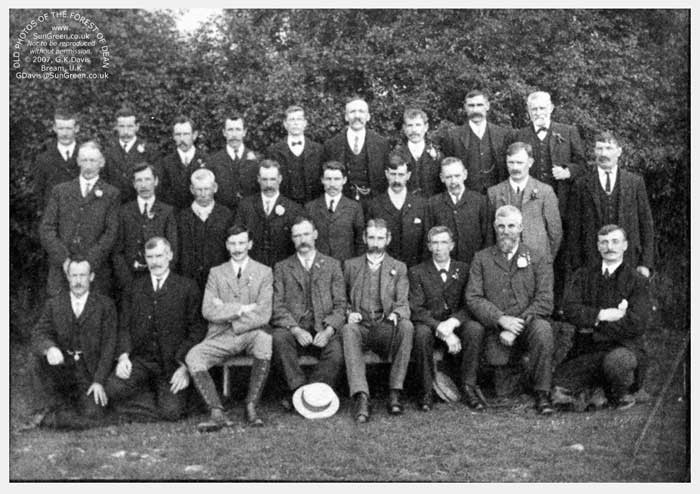

John Williams

In March 1922, Herbert Booth handed in his notice as the agent for the FDMA and was replaced by John Williams, a 34-year-old miner from the Garw Valley in South Wales. Williams’s first task was to set about rebuilding the FDMA after the defeat of 1921. In 1924, the depression in the coal trade slackened, and by 1925, Williams had rebuilt the FDMA from about 1300 members to nearly one hundred per cent membership of 6500 by 1925.

In December 1922, Williams organised a reception for about 30 miners who were part of a contingent of unemployed miners returning from London. They had walked from South Wales to London on a hunger March which was organised by the National Unemployed Workers Committee. Williams helped to arrange for them to stay at the Westbury workhouse overnight, where they were given supper and breakfast before proceeding homeward the following day.[54]

Despite the depression in the coal trade easing in 1924, there were still many miners out of work and some were forced to appeal to the Guardians for help. During a discussion at the meeting of the Monmouth Board of Guardians in early December 1925, Mr C. Lipsoomb argued that the unemployed should be forced to move to districts where there was work. Mather-Jackson said:

they should encourage young men who wanted to go abroad to work, but she did not think any of them would like to compel men to go abroad.[55]

Thomas Neems, an unemployed labourer from the Forest of Dean, responded:

I am on the dole myself. It is not nice to be accused that you are not willing to work. There were, he added, some men among all classes who would not work. He urged the development of the land in the Forest of Dean.[56]

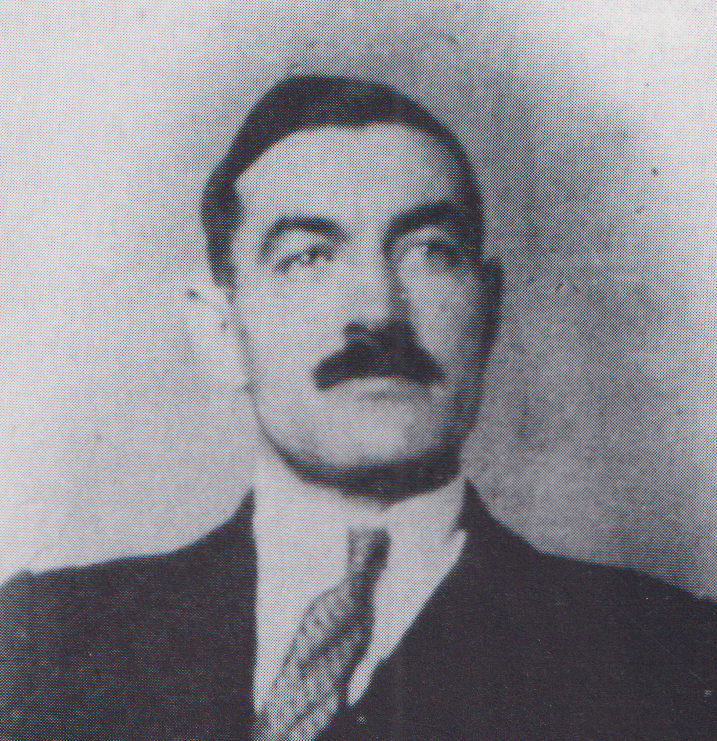

Mason and Brain

In 1922, Charles Mason joined Tim Brain on East Dean District Council when he was also elected to represent Drybrook as Labour councillor.[57] Mason worked at Cannop colliery as a collier and was an active member of the FDMA representing Cannop on the FDMA Executive Committee. Brain still worked at Cannop in a supervisory role as a deputy.

East Dean District Council was chaired by George Rowlinson and Mason and Brain became good close friends and political allies. Their focus was on fighting for the rights of the poorer people in their community. In April 1923, the Dean Forest Mercury reported that:

A motion was brought forward that the Council consider the question of wages that unskilled labourers are paid by the Council, the mover being Mr. C. E. Mason with Mr. T. J. Brain seconding. An amendment referring the matter to the Finance Committee was, however, passed. It was stated that the present wage was 36s per week.

In 1923, they were both elected to the Westbury Board of Guardians. Mason and Brain immediately came into conflict with some of the older members of the Board. They were keen to represent the interests of the residents but often got a hostile response from the chairman, George Rowlinson. On 12 November 1924, the Gloucestershire Echo reported:

Mr. C. E. Mason, at a meeting Tuesday of the Westbury-on-Severn Guardians, reported that some of the old man had confided in him that for more than a month both meat and bread were deficient as to quantity and quality, whilst vegetables – potatoes chiefly – had been scarce. Mr Mason suggested the complaint deserves an inquiry. Three old men—one on crutches—came before the board, and bore out Mr, Mason’s statement. The Chairman (Mr G. H. Rowlinson) and several guardians said that such a serious complaint could not be allowed to pass unchallenged, and at the Chairman’s suggestion the house committee was instructed to hold an inquiry The Chairman said that he had himself dined off the ordinary menu, which ought to satisfy anyone.

Stone Yards

By the beginning of 1926, the depression in the coal trade had deepened again and unemployment increased. One consequence of this was that some Boards of Guardians in mining districts were in debt to the government because of loans from the Ministry of Health, causing some Poor Law Unions to become close to bankruptcy.

However, Boards of Guardians responded in different ways to the huge increase in unemployment. On 26 February 1926, the Monmouth Board of Guardians set up a committee to provide work for the able-bodied unemployed men and on 16 March 1926, the Guardians made arrangements to negotiate with Monmouth Council to set up a stone breaking yard.

It was not long before destitute, unemployed, able-bodied men were put to work in the Monmouth stone yard. The rates of pay were 7s 6d a week for a man and 7s 6d a week for a wife and 2s for a child. The boring and physically demanding work of breaking stone by hand was paid at 2s per ton up to the full amount of relief. Alternative work was offered for the less able, which included sawing wood or gardening at 4s 6d a day. Any other income would be considered and deductions made, and 75% would be paid in kind.

However, some Boards of Guardians in working-class areas continued to earn the Ministry of Health’s disapproval by refusing to introduce stone breaking yards while granting unconditional outdoor relief to the unemployed and adopting what was regarded as over-generous scales of relief.

The number of labour movement-dominated Boards during the 1920s never exceeded 50 out of 620, but their actions had an impact elsewhere. [58] The Forest of Dean Boards provided only a minimum amount of relief and were reluctant to get into debt. Significantly, the action of the more militant Board members in mining districts in the North East and South Wales would inspire some Labour Party members on the Forest of Dean Boards to argue for more generous relief during the 1926 lockout.

The 1926 Lockout

On 1 May 1926, having refused to accept an increase in hours and a reduction in pay, one million miners across Britain were locked out again. This included nearly 6500 miners from the Forest of Dean. The FDMA was still in debt and could not provide strike pay. The cooperative societies and traders were reluctant to provide credit because many were still owed money by the FDMA, so it was not long before some families became destitute.

Nationally, the increase in Outdoor Relief rose between September 1925 and September 1926 from 123 per 10,000 of the population to 452 per 10,000 which was equivalent to 1,757,124 people.[59]

On 5 May, the Ministry of Health sent out a circular (703) which confirmed that under the Merthyr ruling, no relief was available to able-bodied single men unless they were destitute and physically incapable of work, in which case they could only be offered a bed in the workhouse. The Merthyr ruling stated that the dependents of striking miners, such as wives, children under fourteen and widowed mothers, could be helped if they were in severe need. Circular 703 also added that the Guardians should not be concerned with the merits of the dispute.

The ruling was particularly problematic for single men who often lived in lodgings or with family members, and so became dependent on the families with whom they lived, adding an extra burden to those households. Single men who were solitary migrants from other parts of the country and lived on their own were particularly vulnerable. This meant that many single miners who had emigrated to South Wales returned to the Forest to be supported by their families.

The government was aware that any relief for wives and children could be shared with their locked-out men, so they were determined to limit the amount of relief available. Circular 703 made recommendations as to the maximum amount of relief that the Boards of Guardians should give. Legally, the government had no power to do more than recommend. The suggestion was that relief should not exceed 12s for a wife and 4s for each child.

“Children” is generally taken to mean children under fourteen and any child who had left school and had gone to work or sought work was not allowed relief. However, the MFGB argued that since 14 to 18-year-olds were denied the opportunity to have full union membership and the attendant right to a voice in industrial policy, they did not participate in the decision to go on strike and so should be eligible for relief. The Ministry of Health refused to accept this argument and so the pit boys were denied relief.

The Ministry of Health argued that any money coming into the house from other sources, such as an older son or daughter or a pension, could be deducted from the weekly allowance and relief was denied to those who had savings. It was recommended that families of miners who owned or were buying their property with a mortgage should also be disqualified from relief on the basis that they could sell or remortgage their properties. No additional allowance was recommended to cover rent.

Each Board and each Board member responded to this advice differently. In general, those Boards where the labour movement was not in control followed the guidelines. Where the labour movement was in control an endeavour was made to give more adequate relief. However, to do this it was often necessary to ask the Ministry of Health for a loan or permission to borrow from a bank. The problem for the Boards was that they could only borrow with the Minister’s sanction and on the conditions which the Minister laid down. Since those that had to borrow were those with the largest mining population, the Minister was able to require reductions in their relief scales as a condition for loans.

During May, hundreds of families from the Forest applied for relief and some was paid out to wives and children of miners in food vouchers or cash and initially only for two weeks. The Labour Party members on the Boards were in a minority, but over the next few months did their best to challenge the legality and morality of the decisions made by the majority of the Guardians, who were mainly from upper or middle-class backgrounds. Most of these Guardians had spent many years sitting on committees and were well-versed in using legalistic arguments and bureaucratic manoeuvres to undermine those Labour Party members who were less knowledgeable or experienced.

Feeding the Children

The Forest mining community set about the task of feeding the families. Some children were sent away to friends and relatives, while some miners’ wives and daughters left the Forest to earn money as servants in the big cities. Soup kitchens were organised in every village and there were local distress funds that accepted contributions from those at work. The women in the community were at the forefront and kept busy every day preparing and cooking food.

The Central Relief Committee in Cinderford operated from the town hall. The delegates on the committee were made up of representatives from across the community and liaised closely with representatives of the local religious organisations. Money was collected from the churches and chapels and the wider community and it was agreed to avoid soliciting donations from the shopkeepers, who also were under financial stress.[60] The Gloucestershire Federation of Labour Parties also arranged to make collections throughout the county for miners from the Forest Dean and Bristol.[61]

Legislation introduced in 1921 conferred discretionary powers on local education authorities to provide school meals to children who, through lack of food, were unable to take full advantage of the education provided. Charles Luker and Jim Jones, who were both Labour Party members of the County Council Education Committee, were instrumental in persuading the Committee to contribute 5d a child towards financing a daily school dinner for the children of miners.[62]

The committee of the Forest of Dean School Managers took on the task of liaising with the headmasters of the schools. School Managers Committee member, Jim Jones, said they should endeavour to provide two meals a day. However, George Rowlinson, who was the chairman, said one good meal at midday would suffice.[63] In contrast, many education committees in other mining districts provided funding for breakfast and dinner. By the end of the lockout, the County Council had provided £484,163 of funding at a rate of 2.3d a day for the children of miners in the Forest of Dean and Kingswood. Some other County Councils provided more funding than this.[64]

Westbury Union

In 1926, Labour Party members on the Westbury Board included Frank Ashmead, Abraham Booth, Tim Brain, Harry Morse and Charlie Mason, all elected from East Dean District Council. Mason was now a locked-out miner. Brain was still employed as a deputy at Cannop Colliery where he continued to work during the lockout to prevent flooding and to maintain the pit. Morse, also a locked-out miner, worked at New Fancy colliery. He lived in Blakeney and was elected as a Labour Councillor on East Dean District Council in 1925 and then onto the Westbury Board.

Most of the remaining members of the Westbury Board were senior members of the establishment. Most owned their businesses as shopkeepers, tradesmen or farmers and nearly all were employers. Two were members of the aristocracy. They were vehemently opposed to the action of the miners in refusing to accept a reduction in wages and an increase in hours.

The chairman, George Rowlinson, had fallen out with the FDMA and the mining community and sat as an Independent; he was sometimes hostile to the miners. Ashmead was an ex-miner who had worked closely with Rowlinson when he was the agent for the FDMA and, out of loyalty, he often backed Rowlinson up in the meetings. Rowlinson also had the backing of fellow district councillor Richard Westaway, a grocer from Cinderford.

On Friday 7 May, there was a long queue of miners outside the office of the Westbury relieving officer for the Cinderford area, who was registering applications for relief. Consequently, by mid-May, the Westbury Board had received over 700 applications from the families of miners. On 11 May, an emergency meeting of the Westbury Board met to discuss how to deal with the requests for relief.

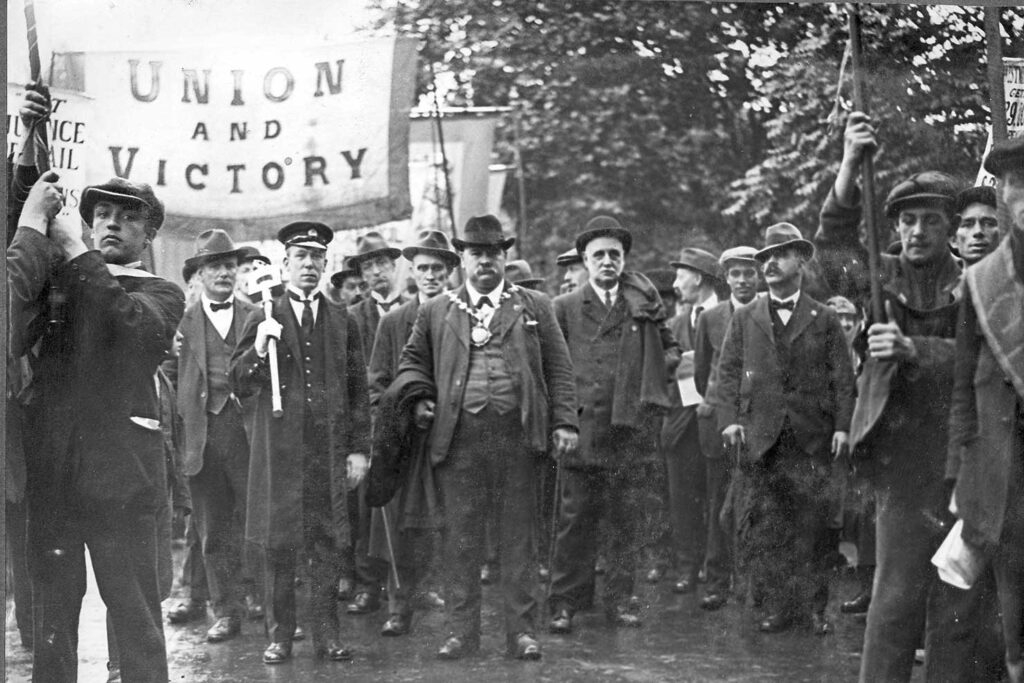

In response, John Williams and the FDMA organised a demonstration to argue the case for relief. As a result, a large contingent of East Dean miners and their families walked or cycled to Westbury-on-Severn to lobby the Westbury Board meeting. At the beginning of the meeting, the Board agreed that they would receive a deputation from the demonstration to hear their case when they had finished their discussions.

During the discussions, Rowlinson said it might take a week to deal with all the applications and each case would be considered on its merit. After a long discussion, it was agreed that relief could only be offered to women and children and a weekly allowance of 10s for a miner’s wife, 4s for a first child and 2s 6d for other children up to a limit of 25s was decided upon. The relief would not be a loan and they would receive the allowance of 25 per cent in cash and 75 per cent in vouchers to be exchanged in local stores. The relief would be granted for only two weeks, after which the cases would be reviewed. Mason volunteered to join eight other Guardians on a relief committee to meet in Cinderford to consider further applications for relief and to grant relief according to the above scales.

These allowances were below the rates suggested by the Ministry of Health. In contrast, some Boards of Guardians awarded rates above the recommended levels. These Boards included Chester-Le-Street, Gateshead, Lanchester and Sedgefield in the North East, Rotherham and Hemsworth in Yorkshire and Bedwellty, Llanelli and Pontypridd in South Wales.

Throughout the meeting, there was some tension between some of the Board members, particularly between Rowlinson and Mason, who did his best to argue in the interests of destitute families and single men. At one point, Mason challenged Rowlinson’s claim that the law said that destitute single miners could not be admitted to the workhouse. There had been disagreements between these two men in the past, such as the time Maon made complaints about the amount and quality of the food.

The attitude of some of the Guardians appeared to be that the money belonged to them as ratepayers and they were donating it to the mining families out of charity. During the discussion, Mason made the point that the miners were part of the community too and paid rates and so were entitled to benefits as of right in time of need. Daniel Walkley, who ran a transport business in Cinderford, and J. S. Bate, an estate agent from Blaisdon, claimed that their duty was to the ratepayers and that the young single miners could not be destitute because work was available to them. The Dean Forest Mercury reported Mason’s reply:

Where? …As the youngest member of the Board, he understood his duty quite well and was not going to Mr Walkey to learn it. He was representing the public, and a most essential part of the public. The miners were in the public area. He took it that young men also put money into the fund for administering the Poor Law.[65]

Mason went on to argue that the Board’s duty was to consider the destitution of members of the community in assessing whether relief should be provided. He added that the Ministry of Health had stated that the Guardians should not take sides in industrial conflicts, which it appeared as if they were doing.

Williams and Thomas Etheridge, the full-time financial secretary of the FDMA, were then invited into the meeting as representatives of the delegation.[66] They presented a case for relief for all miners, particularly the single men, arguing that it would be humiliating for them to enter the workhouse. He added that another vulnerable group was made up of those who owned their houses or were paying a mortgage, as they were in danger of losing their property if they could not keep up payments. He asked for relief to be paid wholly in cash to prevent exploitation by tradesmen.[67]

When addressing the crowd of miners and their families outside after the meeting, Williams reported that the Board had decided that the cases of able-bodied single men would not be entertained but if completely destitute, they may be allowed a bed in the workhouse. He reported that the cases of house owners would be considered on merit and any money received from the MFGB or elsewhere would be deducted from the allowance. As a result, the FDMA decided to refrain from allocating any funds from the MFGB or other donations to those families receiving Poor Law relief. The relief would be paid out at Wesley Hall in Cinderford on Saturday mornings. Williams added:

I want to acknowledge we owe the Board of Guardians something for the courtesy they have shown us this morning.[68]

In the evening, a large meeting was held at Cinderford Town Hall and chaired by Jim Jones, who started the evening by singing a song. Williams reported on the events at Westbury in the morning. He added that if many destitute single men could not get any relief, then they should turn up on mass at the workhouse and demand to be admitted. He thought it would be unlikely that the workhouse would have enough beds to deal with a large number of applicants. He reported that the FDMA was going to ask Jones and Luker if they could make a case to the County Council for two meals a day for children rather than one.[69]

A further source of help emerged when, at a meeting on 23 May, Williams announced that £260,000 had been sent by Russian miners towards an MFGB distress fund, of which £1,500 had been allocated to the FDMA.

Monmouth Union

In 1926, the following guardians on the Monmouth Board were Forest of Dean Labour Party members or sympathetic to Labour: Charles Luker (Labour Party agent and ex miner), Ellen Hicks, E. Alice Taylor, Albert Brookes (locked-out miner) and J Willetts (locked-out miner).

An emergency meeting of the Monmouth Board was held on Wednesday 12 May. The Board was chaired by Lady Mather-Jackson, who confirmed a similar rate to Westbury: a weekly allowance of 10s for a miner’s wife and 3s for a child, but in the form of a loan up to a maximum of 25s per week.

Wilkes, the relieving officer for the Monmouth Board, said that he had already dealt with 200 cases at an average cost of one pound per case, paid out in vouchers at the above rate. He added that on Tuesday 4 May, the applicants came to Yorkley and he told them he could not relieve the able-bodied men. After collecting more food vouchers from Monmouth on Friday, he complained that:

When I got home at 5 o’clock I was besieged … On Saturday night I could not do anything with them. The police came down and since then I have been under police protection.[70]

F W Neems, who was among the fifteen members from the Forest of Dean, argued that: