This is a story some of you may have come across before. I have included some further information about some of the characters involved and provided some background that may or may not be relevant and is a bit of a mish-mash of information. Any thoughts or further information on the story would be appreciated.

In 1587 a Newland tanner, Edward Whitson, transported a cargo of calfskins by a boat owned by John Gethin from Brockweir in the Wye Valley to a French ship in the Kings Road (near Avonmouth) in the Bristol Channel provoking a violent confrontation with Bristol merchants who claimed a monopoly on the export of calfskins. The merchants were led by Thomas James who was born in Woolaston in the Forest of Dean. The confrontation resulted in the murder of Gethin by James. According to William Adams writing in 1623:

“This year in July 1587 near about St James fair Mr Thomas James and many other merchants of Bristol, having obtained letters patents from our Queene for the sole transportation of calf-skins, and having intelligence that a woodbush of Brockwere was loaden with calfskins by Edward Whitson of Newland in the county of Glowcester, tanner, to be shipped aboard a French ship called the Esperanso in Kingrode, without compounding with the merchants for the same transporting or of paying any other custom: whereupon Mr James, Thomas White, John Brimsdone, merchants, and others to the number of 13 went from hence in the searcher’s pinnace, having one musket, half pikes, and some other offensive weapons, to meet the said woodbush and to make seisure and forfeit of the said goods prohibited. The forest men were bold, and suspecting blows might happen, ye said Edward Whitson, with Walter Ely and others to the number of 11, had well fitted themselves with bows and arrows, pikes, targets and privy coats, stronger than our men for offence and defence. They met in Kingrode, resisted and shot arrows at the pinnace, whereof Mr Thomas White and others were hurt: but our men being hurt and so moved in their own defence, a musket was shot off (supposed) from Mr James, which killed John Gethen, master and owner of the boat, for which the 2 sheriffs troubled him and seized upon his goods and others’ that were with Mr James. But Mr James himself was indicted and arraigned at the Marshalsie in Sowthworke, and when no man gave evidence against him he was released as not guilty; but it cost him much besides his trouble. Thomas Kedgwin wrote otherwise, but I knew the business better than he.”

The Society of Merchants Venturers was established by a 1552 Royal Charter from Edward VI granting the society a monopoly on Bristol’s sea trade. The society interpreted this as a granting of a monopoly on all trade within the Bristol Channel. However, the granting of this Charter ran counter to customary rights held ‘since time memorial’ by traders in the Forest of Dean who regularly sent their goods by sea to Ireland and France. The 1552 Royal Charter represented a breach of customary norms by the emerging mercantile class represented by the Merchant Venturers in claiming ownership of resources that had traditionally been held in common. In doing so they ran into violent conflict with a community from Brockweir in the Forest of Dean whose strongly held belief in custom and practice meant that they would defend their interests with the use of arms.

Thomas James (1555-1619)

Thomas James was also a member of the local Forest of Dean gentry. His father, Edward, migrated from Brecon to Woolaston on his marriage to Margaret Catchmay-Warren. Margaret’s father was William Warren from Hewelsfield Court near Brockweir. Her mother was the daughter of Mariana Catchmay who was the daughter Sir Thomas Catchmay who owned the Bigsweir Estate just up the Wye from Brockweir.

As a young man, Thomas James migrated to Bristol and served an apprenticeship as a merchant where he engaged in trade with the Spanish with whom he fell out and was later accused of corruption. He married Anne Gough in 1578 and had fifteen children.

Ann Gough was the daughter of William Gough (1535 -1626) and closely linked to the ownership of Hewelsfield Court. After the death of William Warren in 1573 Hewelsfield Court passed to George Gough, who had married William’s daughter Mary (Margaret’s sister) who then held it as a widow.

Their son another William Gough succeeded to their Hewelsfield estate, and it later passed to his son Richard Gough who left it to his daughters Alice, wife of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, and Eleanor, wife of Sir William Catchmay.

Henry Gough, who was probably Ann’s brother, was another member of this extended family who migrated to Bristol and became a merchant venturer. He was elected Sheriff of Bristol 1585-86. Gentry families were often closely connected and intermarried!

Thomas James became a very successful businessman and a leading member of the Merchant Venturers. Thomas James acquired over 400 acres of land and property in the Forest of Dean in Woolaston and Tidenham area close to Brockweir.

Trade with Spain

Thomas James gained a considerable amount of his wealth from trade with Spain. The merchant venturers were primarily interested in power and money and were not concerned with the interests of the developing nation state. Consequently, they did not allow war with Spain to interfere with their trade. Dr Richard Stone, Lecturer in the History Department at the University of Bristol has discovered that in Bristol:

Data from the port books and wharfage books show that in spite of England being at war with Spain 1563-1608, there was no decline in trade, which rose from £12k in 1563 to £34k in 1600. Some of that can be attributed to licensed privateering, up to a third in 1595-5, but most of it was ordinary trading, which was illegal but evidently profitable. Computer analysis by region of Bristol’s trade in 1600-1 shows imports from, but no exports to, Spain. That suggests that Bristol ship owners or captains were making false declarations for customs purposes. Bristol merchants probably had closer relationships with Spain than with London. Similar analysis of Bristol’s exports to France 1600-1 show most going to La Rochelle but also to Bayonne and St Jean de Luz, close to the Spanish border. In 1594-5 most exports went to Brest and La Rochelle. Bristol’s trade with St Jean de Luz was particularly active during wartime, notably 1600-1 and1624-5

On the import side, analysis by commodity of trade 1594-5 shows goods coming in from St Jean de Luz, in fact coming from Spain. Analysis by origin of imports 1594-5 shows a cluster of places of origin around Seville, eg Cadiz. Seville was prospering because of the influx of silver from the new world: it would be understandable for Bristol merchants to want to cash in. Data for 1600-1 show Seville sending goods to Bristol. The inference is that Bristol merchants were declaring that they were trading with ports in France eg Toulon, but were in fact trading with Spain. In 1575 shipping from Spain was dominated by English ships. In 1600 English ships were engaged mostly in privateering or were transferring to neutral destinations. The conclusion is that merchants all over Europe were co-operating to make trade happen, irrespective of war.

The Forest of Dean

When William Camden’s Britannia, was first published in 1586 it reinforced the reputation of the Forest of Dean as a ‘dark and terrible place’. Camden wrote that the Forest of Dean:

“was a wonderful thicke forrest, and in former ages so darke and terrible by reason of crooked and winding, as also the grisly shade therein, that it rendered the inhabitants barbarous and emboldened them to commit many outrages. In the reign of Henry VI they so annoyed the banks of the Severn with their robberies, that there was an Act of Parliament (8 Henry VI) made on purpose to restrain them.”

Although some such attacks did take place Jason Griffiths points out that:

“the reference to an act of Parliament serves to re-enforce both the significance of the attacks and to set up a binary opposition between central government and this unruly region needing to be restrained, a recurring trope in Forest of Dean literature. In amongst the trees, the dark forest, starved of actual and metaphorical light, is engendered barbarity and lawlessness.”

The Forest of Dean had a highly distinctive social, political and economic history for several reasons The Normans kings designated it as an ancient royal forest to be used for hunting by the King. However, it also contained within its boundaries rich deposits of coal and iron ore which could be reached by the digging of shallow pits. In addition, there were large stands of oak suitable for construction. Therefore, it was only ‘a dark and terrible place’ to outsiders but a highly industrialised place with the economic and social life of its population regulated by its own local laws established through custom and practice over generations.

The inhabitants also had to abide by Forest law laid down by the Crown to protect the deer for hunting. During the sixteenth century, the royal forest administration harvested some of the timber for shipbuilding and made a small profit selling cordwood to smelt the locally mined ore and bark for tanning. However, by the second half of the sixteenth century, the forest had fallen into neglect by the authorities and the local inhabitants were permitted to exploit the forest almost at will.

As result, the inhabitants treated the Forest as their own, encroaching on Forest land building cabins, drawing sustenance from its woods and wasteland above the surface and minerals below, in particular coal and iron ore. Timber was used in coal mines and for building and wood for making charcoal. Since veins of ore were close to the surface, workable pits could be dug by as few as two or three men, with virtually no capital outlay. The miners were members of a close-knit community that had its own court for the settlement of all mining disputes and by custom and practice claimed unrestricted rights to mine coal and iron ore in all lands within the forest bounds. Ore mined extensively in the area around Bream and Coleford would have been transported past Orepool in Sling to St Briavels or Stowe and to Brockweir and then up the River Wye to the Severn.

Grazing and Wood

The right to common, pannage and estovers was also claimed by the people of the Forest of Dean for centuries and the local population ran animals to graze in the woods. The tenants’ right to common pasture in the royal demesne of the Forest was exercised mainly in the detached areas that adjoined their parish.

The area between Brockweir, Hewelsfield and St. Briavels was bounded by a great tract of extraparochial land called Hudnalls. In 1608 it covered 1,205 acres and comprised the land later distinguished separately by the names Hudnalls and St. Briavels common with the north and west parts of the land later called Hewelsfield common. Although encroached upon, the extra-parochial areas remained part of the royal demesne of the Forest until the 19th century.

Brockweir was part of the Parish of Hewelsfield which also contained the village of Hewelsfield further inland from the Wye. The tenants from the parishes of Heweslfielsd and St Briavels claimed an ancient right to cut and take wood at will from the Hudnalls. They ascribed this right to a grant by Miles of Gloucester, earl of Hereford, recorded in 1282 when they were said to be destroying the woodland. A Perambulation of the Forest of Dean 1281-2, appertaining to the Boundary of the Bers (Berse) one of the Bailiwicks.” It reads:

“The Wood of Hodenhales is a royal forest of the King and is cut down by the men of St. Briavels. These men claim the right of taking wood thence for themselves freely and have always taken it from there.”

It was interpreted as more extensive than the estovers claimed by the tenants in other parishes adjoining the Forest. Hudnalls probably supplied some of the regular trade in wood from that part of the Wye Valley from Brockweir to Bristol for coopers and other craftsmen. An ancient ceremony involved the distribution of bread and cheese to the poor in St. Briavels church at Whitsun and by tradition, it was instituted in connexion with a grant of a right of taking wood in Hudnalls.

Noblemen, Knights and Gentry

The Forest in inhabitants also included the local gentry who owned land surrounding the statutory Forest. In addition, noblemen who were royal favourites were granted leases to farm parts of the Forest. These included Sir William Herbert, first Earl of Pembroke, Sir William Wintour, Richard Breame, and William Guise. In doing so they sometimes came into conflict with the inhabitants of the Forest and local gentry, particularly if they were taking more wood than was agreed in the lease as was often the case.

Among the local gentry were the owners of the Bigsweir estate which lay on the Gloucestershire side of the weir and was originally owned by the Bishops of Hereford. The freehold to the estate passed to Thomas Catchmay in 1445. It remained the main house and estate of the Catchmay family for several centuries. Thomas Catchmay already held other lands. John Catchmay was living at Bigsweir in 1509 and Thomas Catchmay in 1555. By 1608 the Bigsweir estate was held by George Catchmay who then employed at least eight servants. Thomas Catchmay (born 1445) was Thomas James’ great grandfather on his mother’s side of his family.

The man who hired Gethin and owned the calfskins was Edward Whitson (1540-1629), a member of a gentry family from Newland. In 1610 he was recoded as being a church warden at Newland church. Members of his extended family included the brothers John Whitson (1557-1629) and Christopher Whitson (1545-1605), sons of William Whitson both born in Clearwell, the village next to Newland.

In his book John Whitson and the Merchant Community of Bristol published by Bristol Historical Association in 1970, Patrick McGrath describes Whitson’s career, fame and fortune.

In September 1570, when Whitson was about 14 or ·15 years old, he was bound as an apprentice as a merchant to Nicholas Cutt who was the fifth son of a wealthy merchant and alderman, John Cutt. The family had a house in Corn Street and had purchased the manor of Burnett in Somerset which was later to be acquired by Whitson himself. Nicholas Cutt had taken up the freedom of Bristol as a merchant in 1568 and the next year he married Bridget, the daughter of another rich alderman, Robert Saxey.

After the death of Nicholas Cutt, Whitson married Bridget and succeeded to the business which provided the basis to subsequent wealth. When Philip II laid an embargo on the English ships in 1585, Whitson fitted out the Mayflower to make reprisals. Her cruise was successful, but Whitson sold her to Thomas James. He became involved in the early voyages for the settlement of North America sending out Martin Pring. He became a member of the Merchant Venturers and major of Bristol in 1603 and 1615. He represented Bristol in four parliaments, in 1605, 1620, 1625, and February 1625–6. He married two more times into very rich families increasing his wealth and power but died from a fall from a horse in 1629. In December 1614 Whitson and four other leading Bristol Merchant Venturers were licensed to export 1,000 calfskins yearly for 40 years at preferential rates.

Tanning

Tanning is the process of treating skins and hides of animals to produce leather. Tanning hide into leather involves a process that permanently alters the protein structure of skin, making it more durable and less susceptible to decomposition, and also possibly colouring it. Before tanning, the skins are dehaired, degreased, desalted and soaked in water for six hours to two days. Traditionally, tanning used tannin, an acidic chemical compound from which the tanning process draws its name, derived from the bark of oak.

In 1608 the muster for Newland tithing (which comprised the Newland village area and the Redbrook area in the Wye valley) included 26 tradesmen and craftsmen. There were five tanners, most probably working in tanneries on Valley brook near Newland village, where they were conveniently placed for the Bristol, French and Irish trade using the Wye and for a supply of bark from the Forest woodlands.

A complex set of rights, customs and practices determined by custom and usage regulated industry and trade between the Foresters and others. Iron, cordwood, timber and calf skins were transported to Ireland and France via the River Severn and Wye and boatmen on the Wye had a close relationship with the miners and other Foresters. The river community in Brockweir was a close-knit community and was one of the centres of this trade. It is reasonable to assume that miners, woodmen, traders and boatmen from the Forest of Dean believed they had the unrestricted customary right to trade with whom and where they liked since time immemorial.

Brockweir

Brockweir lies on the bank of the Wye where the Brockweir and Mere brooks enter the river. Brockweir had some houses by the late 13th century and provided a substantial part of the Parish’s population by the mid-sixteenth century.

Medieval Brockweir was closely associated with nearby Tintern Abbey. Hewelsfield manor was retained by Tintern until the Dissolution when the abbey also had a grange at Brockweir, which probably comprised buildings and land adjoining in Woolaston parish where Thomas James was born. Manor and grange were granted with the other abbey estates in 1537 to Henry Somerset, earl of Worcester. The manorial rights of Hewelsfield passed to his descendants, the earls of Worcester and dukes of Beaufort. Little evidence for the early agricultural history of Hewelsfield has been found, but the original pattern of tenure, as in other manors created on the Forest fringes, was probably one of the small freeholds. The medieval manor of Hewelsfield had little agricultural land in demesne, though it did include some woodland.

In 1551 there were reported to be eighty communicants (church members) in the parish and in 1563 twenty households. At that period the small population was roughly divided between the two villages of Brockweir and Hewelsfield. The population was estimated at forty families in 1650 and two hundred people in forty houses in 1710.

Industrial and economic activity in the area was boosted in 1568 when the Company of Mineral and Battery Works established in 1565, built wireworks at Tintern which was just down the river from Brockweir. The products included cards for the woollen industry, nails, pins, knitting needles and fish hooks. The site was convenient because the Wye offered transportation to markets. At the end of the sixteenth-century gentry and noblemen started to take an interest in the iron business and George Catchmay acquired the lease of the Tintern wireworks with several other noblemen.

Lawless Elements

For centuries many inhabitants of Brockweir were employed in the trade of the river Wye including transport and boat building. In 1563 there were thirteen sailors registered in the parish of Hewelsfield. Brockweir was the highest point reached by a normal tide on the Wye and a key transhipment point. The products of Herefordshire, Monmouthshire and the Forest of Dean (principally iron and timber) were sent back to Bristol and beyond.

Brockweir, approached as much by water as by road, was an isolated community with an independent character. Only one narrow road led into the village, and goods were usually carried by donkeys or by water, with a ferry taking travellers to and from the Welsh bank of the Wye. It was a notoriously rowdy place full of dockers, sailors and bargemen. The minister appointed to its new Moravian church much later in 1832 described the life of its watermen as being centred on beerhouses, skittle alleys, and cockfighting and said that it had the reputation of a ‘city of refuge’ for lawless elements. Of course, this characterisation of ‘the lawless elements’ in Brockwier was the view of an outsider whose mission was to ‘save them’ and convert them to his religion.

John Gethin

John Gethin inherited his boat from his father, also John Gethin. J J Dicker describes Gethin as a prosperous man:

In in 1571 we find John Geathene the elder leaving by will his ‘best boat’ to his eldest son and his ‘second boat’ to his second son, with the proviso “my wife to have use of the boats to carry to Bristol the wood I have on Wye bank.” Geathene was a prosperous man for he left £10 each to his third son and two daughters (both named Joan). It is probable that John Geathene had been married twice and had a daughter Joan by each wife. This duplication of names was not infrequent in the middle ages.

As a relatively wealthy man, Gethin was probably a leading figure in the small community of Brockweir but dependent on local custom and practice to pursue his trade. Gethin and his men would also have been well-armed.

The Armed Hand

In reference to the military muster of 1522, David Rollison concludes that, at this point, the men of the Forest of Dean were amongst the most heavily armed and trained of all English districts. He concludes the following:

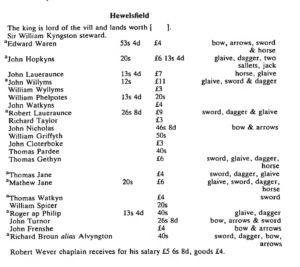

The weapons and armour presented by the Hundred included 112 swords, 121 daggers, 8 shields, 114 glaives, 31 sallets, 18 Forest Bills, 7 horse and harness, 13 horses only, 16 harness only, 4 almain rivets, 1 lance, 22 hauberks, 5 gorgets, 1 splint, 1 axe and 1 javelin. Of 621 men recorded in the returns, no fewer than 408 were in possession of a weapon and armour, including no fewer than 200 longbows …. The ‘able-bodied’ category included men who were fit for military service: we must assume that many older and less fit men were also capable of using their weapons at target practice and hunting.

The list above is the 1522 Muster for Hewelsfield which includes Brockweir. The name Thomas Gethyn appears in the muster and may have been a relative of John Gethin. In 1539 fourteen men were mustered under Hewelsfield and ten under Brockweir and the corresponding figures in 1546 were eleven and nine. Later the balance swung fairly heavily towards Brockweir.

Conclusion

In the years after this event, Thomas James became one of the most powerful figures among the mercantile elite in Bristol and built up a fleet of ships that he used as privateers to attack the Spanish. He contributed a ship to the Cadiz expedition of 1596 which captured, sacked, and burned the city. He was successively Sheriff in 1591, Alderman from 1604 until he died in 1619, twice Mayor in 1605 and 1614, Master of the Merchant Venturers in 1607 and 1615 and Member of Parliament for Bristol in 1604 – 1611 and 1614. During this period the Merchant Venturers consolidated their power and monopoly on trade in the Bristol area.

Meanwhile, James consolidated his property in the Forest. He was granted the rectory of Tidenham by the Crown in 1607 and in 1614 he held a freehold estate of 40 acres from Waldings manor. A mill and land in Woolaston, Hewelsfield, and St. Briavels conveyed to Thomas James by Edward Shere and others in 1583 included a watermill on the River Cone., Another branch of the James family owned an estate based on Stroat Farm.

Given his considerable power and influence in Bristol, it is no surprise that James was able to get away with murder. He died in 1619 as a very wealthy man. The Merchant Venturers that followed him continued to murder and plunder and became notorious for their involvement in the slave trade. However, given the local connections between the main characters involved in the murder is it possible that the conflict also had its roots in competing interests in the Forest of Dean as well as Bristol.

This perhaps was the first shot in a conflict between the Forest of Dean community and the Bristol mercantile elite. In the next century, Bristol merchants to developed financial alliances with various members of the local gentry and noblemen. This led to the increasing polarisation within the forest community between ‘improving’ gentry, industrialists and freeholders, on the one hand, and those who depended on less formal access to the resources of the locality as part of their subsistence and occupational strategies. The foresters resisted and there was rioting.

Finally, in the early nineteenth century, the Bristol Merchant Venturer Edward Protheroe was able to invest his huge wealth gained from the trade in enslaved Africans and effectively take complete control over large sections of the Forest of Dean resources by the development of his coal mines and rail networks.