John Williams was appointed as the full-time agent for the Forest of Dean Miners Association in 1922 and held this post until he retired in 1953. The article on this website, Class Struggle in the Garw Valley, covers his early life from 1888 -1922. The book We Will Eat Grass, soon to be published and available from this website, covers the period of his life in the Forest of Dean from 1922 to 1928.

Williams was much more than a politician and trade union activist. He was a family man and a lover of the arts and music. He also had a fondness for horse racing. His brother, Emlyn, was a gifted violinist and his daughter, Nest, studied piano at the Royal Academy of Music in London. He loved the cinema, and he used to take Nest with him whenever he could.

The text below gives an account of his retirement in 1953. This is followed by transcriptions of two interviews given by Williams to R. Page Arnot in 1961 and 1963; a personal statement of his experiences as the agent for the Forest of Dean miners from 1922 to 1953 sent to Arnot in 1961 and, finally, an account of his death and funeral in 1968

Retirement

On Friday 6 November 1953 the Dean Forest Mercury carried this announcement:

It is with regret that most of our readers will learn that with the retirement of Mr John Williams, the post of Miners’ Agent for the Forest of Dean will lapse. Forest miners have been lucky in that during nearly 70 years there have been but three holders of this key post in what is still our major industry Mr G H. Rowlinson, Mr Herbert Booth and Mr Williams. Mr Booth’s tenure of the office was comparatively short and Mr Rowlinson and Mr Williams each served for 31 years.

Both these gentlemen had a very hard struggle in their first, few years. When Mr Rowlinson was appointed in 1886, out of 5000 miners in the Forest only 50 belonged to the Union; when Mr Williams started in 1922 the position was better, but still, only one-third were in membership. In other respects, Mr Williams had an even rougher passage than his famous predecessor, for his period of office covered the black days of mining between the wars, including the lockout and general strike of 1926 and the depression of the early 1930s. He leaves his ship, however, in calmer waters, though with a much-depleted crew, now that the mines are nationalised and there is a ready sale for every ton of coal produced.

The retiring Miners’ Agent is a man of strong convictions and on that account has not always found it too easy to work with his Executive, particularly in the first few years after his appointment. No one, however, has ever doubted his sincerity or his desire to be of the utmost service to the men whom he represents and miners and the general public alike will join in wishing him health and happiness in his well-earned retirement.

On November 17, when he becomes 65 years of age, Mr John Williams of Cinderford, Miners Agent for the Forest of Dean since 1922, will retire. He leaves behind him a series of experiences gained in a very hard school that tell the story of working-class progress from penury to comparative plenty. His career has been, that of a missionary and it has had all the elements of struggle and frustration and achievement and adventure that make the story complete.

Since Mr Williams has been Miners’ Agent, he has seen the manpower of Forest of Dean coalfield fall from 7000 when he came to the present 3000. Because of those diminishing figures, no fresh appointment of a Miners’ agent will be made. Mrs W. J. Jewell, Mr Williams’s assistant will continue as Finance Officer and Compensation Secretary for this district and she will be closely associated with the secretaryship of the Forest of Executive of the National Union of Mineworkers.

The Forest of Dean was now a shrinking part of the South Wales district of the NUM, and so there was no replacement agent. However, Birt Hinton who worked at Cannop colliery now helped to take on responsibility for local matters as chair of the Forest of Dean branch of the NUM.

In the same edition, John Williams told the Dean Forest Mercury his thoughts on the future of the coal industry in the Forest of Dean:

that if rearmament ceased there would be a glut of coal for commercial purposes as was the case between 1921 and 1939. While we need coal, the nationalised industry is made to stand up to the losses which this district is suffering, but with a glut of coal and the high local costs of production, I doubt if the industry would be expected to stand it. But I believe that there is a prospect of the coalfield carrying on longer than is generally thought. The National Coal Board are making plans at Cannop colliery and Princess Royal in particular for more extensive operations and a more up-to-date system of mining than exists at present.

Retirement Dinner

On Saturday evening 7 November, Williams was Guest of Honour at a dinner at the Unlawater Hotel Newnham arranged by Mrs Jewell on behalf of the Forest of Dean Miners to celebrate his career and retirement. Guests included a large number of his fellow union members and also representatives from most sections of the industry who offered praise “for his wisdom, his ideology and his ability”. The Dean Forest Mercury reported:

Since he came to the Forest in the early twenties Mr Williams, the son of a miner in the Garw Valley of South Wales and himself a miner, has endured storms and struggles that rocked the industry in those distant days, and among the large gathering at the dinner were many who have been with him through it all and they rose to acknowledge a respected leader and to wish him a long and happy retirement.

Father Morrison offered grace and the proceedings were presided over by the chairman of the Forest Miners Executive, Mr B. B. Hinton, who said that it had been a pleasure to work with Mr Williams for the past 13 years, during seven of which he had been chairman and he was able to appreciate the ability with which the agent had worked for the Forest miners. He had done much to raise the conditions of the men from those which existed when he came 30 years ago. “He has been the Father of the Forest Executive”, said Mr Hinton “and if we carry on in the way he has already led us, I don’t think the Dean miners will suffer”.

Proposing a toast to Mr Williams, Mr Will Paynter, president of the South Wales Miners’ Federation said that Mr Williams had been an outstanding character in the miners’ movement for many years. In days of the most acute depression which affected the Forest of Dean as much as South Wales, he secured a job as secretary agent in the Forest coalfield. From that time forward he had been a leading personality not only in the affairs of the miners but generally in the social life of the Forest.

With Mr Williams’s retirement, Mr Paynter went on, he was satisfied that the work he had done and the work he could continue to do would leave its mark for all time on the Forest mining community.

Mr Paynter referred to the happy relations which had existed between the miners in South Wales and the Forest and said it was not their intention to replace Mr Williams with another Miners’ Agent because they had to face the fact that the Forest was a contracting coalfield; manpower was not what it had been when Mr Williams became Agent and they had now made arrangements, in conjunction with the Forest Executive, to maintain the closest contact and leadership between South Wales and the Forest miners’ organisation. They hoped that this new arrangement would function without decreasing the services which Mr Williams had given the coalfield or lowering the high standards he had set.

Paynter said Mr Williams was a leader who was capable of relating the small things which happened in working class life to the larger events – of being able to explain a wages dispute in relation to the general problems of our society, and of being able to give an answer to the wages dispute and the general problems that faced society.

“We have too few in the leadership of the Labour and Trade Union movement off this country”, Mr Paynter said. “who are capable of giving that perspective to events. I am glad to be able to demonstrate in this way tonight our affection for Mr Williams and to express the hope that he will have a long and happy retirement during which he will continue his association with this movement, for I believe he will recognise that this association will be essential to happiness in his retirement.”

Mr Williams replied with an early reference to the help his late wife had given him. “Forest miners will never know how much they owe to her,” he said. “She was counsel for the defence of miners’ rights while she lived and few knew of her work though many benefited from it”. Mr Williams went on to refer to the valuable reforms that had occurred in the movement in his recollection and the two most important, he considered, excluding nationalisation, were the establishment of the eight-hour day and the Minimum Wages Act of 1912. He spoke from personal experience of the long hours that miners often worked to make a living, but that situation ended with the operation of the eight-hour day.

The Minimum Wage Act had far-reaching ameliorating effects, he continued, before its operation colliers working in abnormal conditions received only what was stated on the price list. One of his oldest friends, Mr W. E Parsons, could tell of working at Crump Meadow as a stoker at 2s 6d a shift.

Mr Williams then turned to members of parliament and candidates for parliament he had known in the Forest of Dean, the first of them Mr James Wignall – the most loved of them all. But of all the members and candidates who had come to the Forest in the past 30 years, none could approach their present member, Mr Philips Price, as an intellectual and a scholar.

This present generation is different from his, added Mr Williams, if only because it contained a high percentage of very clever people; his generation produced a small number of great men, and he listed some of them. His generation was concerned largely with ideals and ideas, the present generation was concerned largely with facts. Facts were subordinated to ideas because ideas embraced facts and gave birth to them. There was an ideological struggle prevailing today, but he thought that many of the differences were artificial. If the differences which divided the world today were purely ideological things would not be so bad.

Mr D Evans vice-president of the South Wales Miners Federation added his tribute to Mr Williams, who, he said was born at a time when the movement turned out great men, but he doubted whether we had advanced very much since those days for the forward march of the movement had to be measured not by the steps it had taken but by the steps it could have taken. Today the movement was inclined to turn out men as sausages come out of a machine. Mr Williams’s generation faced realities as they saw them and expressed their conclusions fearlessly – and they were not thought less of doing so. Mr Williams had served the coalfield well during the past thirty years and now they wished him a happy retirement.

Mrs Jewell read messages from several personal friends and colleagues who were unable to attend and each sent a message of admiration and best wishes. These included Sir William Lawther (General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers), Mr Harold Forest, MP for Bedwelty, Mr W H Crews (Secretary of the South Wales area of the NUM), Mr S L Dorrington (Secretary of the Forest Overmen’s, Deputies and Shotfirers’ Association) and Dr W H Tandy of Coleford.

Mrs Jewell then made the “staff presentation” to Mr Williams of “her own gift of an extending lamp “for being such a wonderful boss for the past 13 years”. Expressing his thanks, Mr Williams said the Forest miners were fortunate that Mrs Jewell had been in their service and would continue to be in their service and was grateful to the South Wales Executive for making their excellent arrangement.

On behalf of the Forest Executive Mr Hinton presented Mr Williams with a cheque for £51 with the wish that he would buy himself a bed. Mr Williams thanked the Executive for their gracious kindness.

Tributes to Mr Williams then came from all parts of the room – The first from Mr M Price Philips MP who said he remembered Mr Williams as Miners’ Agent since his first official connection with the parliamentary constituency. He remembered how much Mr Williams had done to build the Trade Union Movement among the Forest miners.

He recalled that an old Mr Miles of Berry Hill had once told him of the first beginnings of the miners’ movement in the Forest in 1870, and Mr Williams had since consummated what he and his colleagues fought for while those on the political side of the movement had helped in their sphere. It was vital that the political side and the industrial side of the movement should work together.

Mr Williams had seen tragic times – the lockout of 1926 at a time when coal was a drug on the market and conditions were anything but favourable for miners to get what was their due. Today coal was as precious as gold and Mr Williams must now feel gratified and thankful for the progress that had been made.

Mr D. N. Lang, who has known Mr Williams in his capacity as a colliery manager and lately Area General Manager for the National Coal Board from which he recently retired, spoke of his admiration of the Miners’ Agent from the days when coal was lying about the collieries and could not be sold at 5s a ton and small coal at 9d a ton. They had always “agreed to differ” and now, on behalf of the colliery managers and the Group Manager (Mr J. R Tallis), Mr Lang presented Mr Williams with a cheque with the suggestion that he should use it to buy a pillow for the bed. Mr William expressed his gratitude.

A tribute to Mr Williams’s leadership in difficult times and as a strategist of unusual ability was paid by W D Jenkins formerly of the Executive and now Labour Officer of the NCB in the Forest. Similarly, and now as chairman of West Dean Rural District, Mr Albert Brookes spoke appreciatively of Mr Williams’s good work in the Forest and his ability to reason clearly which had enabled the Forest miners to benefit from his leadership.

A tribute to Mr Williams’s honesty of purpose to his work for the sick and maimed of the industry and for the Cinderford Miners’ ‘Welfare Hall as president was paid by Mr W. T. B. Nelmes, chairman of Cinderford Parish Council, who was for many years the secretary of the Hall Committee. Finally, Mr W E Oakey (manager of Eastern United colliery) spoke for the colliery managers in warm terms of a well-esteemed Miners’ Agent.

After the. speeches the room was cleared for dancing to Mr Arthur Pope’s orchestra with Mr and Mr L C Upton as MCs.

Williams continued to involve himself in the political, social and cultural life of the Forest of Dean. He remained chairman of Cinderford Miners’ Welfare Hall and was a regular visitor to the union offices on Belle Vue Road which remained open until the end of 1961.[1]

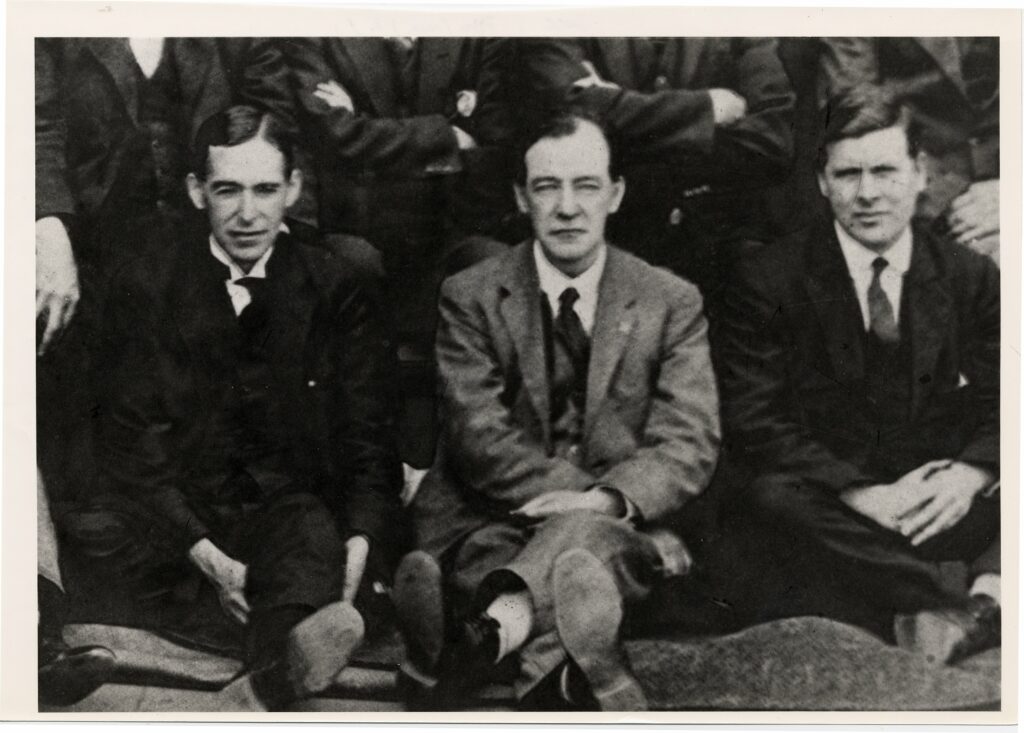

On 10 October 1961, Williams was interviewed by R Page Arnot at the miners’ union offices in Cinderford. Also present were Birt Hinton and Bryn Williams. (Credit Richard Burton Archives)

Jack Williams I visited at around noon and met not in his house at Cinderford, but at the offices soon to be closed, down in the same Belle Vue Road. He retired some eight years ago but was still a regular visitor to the Union office. He lives alone.

Jack Williams was torn in 1888 at Kenfig Hill, near the Garw Valley. His father was a miner; his grandfather had been a mechanic in the mines. He himself entered the mines on his birthday in November in either his 12th or 13th year and the is at which he began was the International.

His earliest recollection as a small child was of the hauliers strike of 1893. He saw the riot, was in a sense actually in the riot together with his father. The manager at Blaengarw whose name was Salathiel, had brought up the militia to protect two blacklegs. The Salathiel family was very widespread and were always to be found holding post offices. He had been with his father as one of the spectators until his father joined up and he remembered his father pushing away at one of the blacklegs.

After he entered the International, he had the experience of being in an explosion. He also worked in the Ocean Colliery and in the Garw Colliery. The occasion of the explosion was this. His father had been boring a hole with a rammer, for shot firing. It was “a flat shot”, that is, the fuse misfired. Now under the regulations, it was necessary to wait 24 hours, but as often happened, the rule was broken and the approach was made to the place when an explosion occurred and burned him severely. J.W. was for six weeks in a bath of linseed oil. He was aged 14 at the time. That was in the days when black powder was used for shot firing. He had begun in the pits at a wage of ls.6d, a day, working with Will Champion.

He remembered Tonypandy, of course, very well and had worked at various other pits in the Garw area so they used to hear about what was happening. The first conference at which he was present of M.F.G.B. was in 1915, Nottingham, when Vernon Hartshorn and James Winstone were Prominent. Big Wallhead, was also prominent. He had been Chairman of the Garw District. lt was there that Frank Hodges became Agent. A peculiar step was taken of asking Hodges and another candidate to address a public meeting. Hodges’ eloquence swept all before him, and though he was less competent than Tad Gill, he was given the agency. As far as J.W. there was some religious background. He thought that Hodges had been a Baptist.

He also remembered others of those days before and during the World War. Outstanding was Noah Ablett. The simplicity and wisdom of his arguments were very attractive. He was rather like Nye Bevan, without Bevan’s speed, but a deeper thinker. He had wisdom as well as swiftness.

Ablett was one of the most sincere men he had ever met. S.O. Davies he also remembered very well, but he, like Mainwaring, was a conciliator rather than parliamentary timber, who had been well used In some big research work. Arthur Horner, always “attractively vain”, J.W.. had worked with, but the man for whom he had the highest respect of all was Harty Pollitt.

J.W.. became a checkweigher in 1914. Here Bryn Williams, who accompanied me, said that he (BW) had become a checkweigher at the age of 17. The Lodge in which J.W. became checkweigher was Cilely (Rhondda). It was the first Lodge to have a 92 per cent membership after the 1926 Lockout.

It was in 1922 in May that J.W. first came to the Forest of Dean as Agent. From the 1874 Amalgamated Association of Miners’ conference record, I was then able to produce the name of Timothy Mountjoy. He agreed that Mountjoy was the earliest Agent in the Forest of Dean, followed by Rymer, followed by Rowlinson. Rowlinson: was succeeded by Booth, who was there only a short time because he could not face up to the problem. That problem was the existence of an enormous debt which had to be cleared off as well as every other sort of difficulty. The debt was £24,000. When J.W. came there were some 30 Lodges, with 8,000 manpower (there are now 2 Lodges).

The Executive Committee of the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association were corrupt, the owners were right inside every branch. Even after he had been an Agent for some time, he found that a pit committee had gone.to London at the behest of the managing director of a colliery and at the expense of the coal owners, to oppose part of the Mines Act. In 1922 there were six candidates, all from outside. No candidate from the Forest of Dean was allowed.

He remembered Herbert Smith very well dour man who had sometimes the capacity to make better speakers look, second rate. Tor Richards was in his opinion, “the ablest debater in the whole of the movement, a man wise and intelligent. Straker, he had a very high opinion of but not so high of Enoch Morrell.

He then recalled the days of the National Minority Movement, when he used to be very much together with Nat Watkins, Arthur Horner, Cook and Harry Pollitt. In Cook, he never did have any great confidence. Once he (J.W.) said to Harry Pollitt about Cook; sooner or later he will sell you out. This proved to be true. In 1926 in the middle of the struggle the negotiations with Rowntree and their group were really a betrayal of the minters’ interests. On the other hand, Cook could show courage. He faced up to the fascists, but he was not always completely scrupulous and this did not accord with the views of J.W.: “I was rather puritanical perhaps”. There is no question that Cook loved the notoriety which he had in the press and elsewhere. For the rest, he could recollect that the first resolution for one single union for the miners was moved by himself, or at any rate, from the Forest of Dean.

B Hinton„ who became secretary in 1953, was also present as well as Bryn Williams, at this interview.

On 23 November 1961, Williams sent a statement of his experiences as the agent for the Forest of Dean miners from 1922 – 1953 to Arnot. (Credit Richard Burton Archives)

A statement of conditions in the twenties and after drawn up by Jack Williams, miners’ agent in the coalfield from 12 May 1922 onwards for over thirty years and sent to me on 23 November 1961 from 52 Belle Vue Road, Cinderford Glos.

I commenced my duties as Miners’ Agent in the Forest of Dean on 12 May 1922. I doubt if I would have taken the job on if I had known what the conditions which existed here at that time. Mr Frank Hodges warned in a mild way that the affairs of the Union in this district were not good. I soon found out how bad things were here.

The coalfield employed about eight thousand miners. There were about one thousand three hundred miners in the union. One colliery employing close on about one thousand miners had only thirteen members in the union.

The Executive of the union had contracted a debt of twenty-four thousand pounds arising out of the 1921 strike. The miners were demoralised. They had no faith in many of the local leaders, and this was to a certain extent understandable as I shall show later on.

I found myself in a strange world. I came from a coalfield where the miners were active and militant. Here the coal owners exercised tremendous influence in the union. I could not understand this state of affairs, and as the months went by I became very depressed. The conditions under which the miners worked was truly appalling. The wages in this coalfield were the lowest in the country. I found men working at the pit-top for four shillings a day at one colliery.

At another colliery, I found that the 1912 Minimum Wage Act had been suspended by arrangement between the union pit committee and the management. The minimum wage under the 1912 Act of Parliament in this district at the time was 7s 71/2d a shift of colliers. Under the agreement mentioned above the owners were able to pay skilled colliers less than 7s 71/2d a shift.

Some years before the Union had contracted pit of the Workmen’s Compensation Act, and had agreed upon a scheme which was decidedly in favour of the Coal Owners. I had been here about nine months before I made a breakthrough, and this happened by accident. A workman came to see me about his compensation. During my talk with him, he let slip something else. He told me that the workmen at his colliery had not received a payment which was due to them. I said to him that we could compel the colliery company to pay this money, but he was not prepared to let me take this on.

I reported the matter at the next meeting of my Executive, and I asked to be allowed to make a claim on behalf of all the workmen at this colliery and to recover the amount due to the workmen. TO my astonishment I was told that I was not to make the claim, on the grounds that the Executive had agreed with the Colliery Company that the workmen had no case. I knew that this was wrong; because the National agreement specifically provided for this payment.

I could stand this state of affairs no longer, and decided to defy the Executive. I went to the Colliery and advised a meeting of the workmen to take action. They were gals to see me, and they authorised me to make a claim. This I did, but the answer of the Colliery Company was “No” to my demand. I went to the colliery again to meet the workmen, and I persuaded them to stop work until they were paid. There was no work the next day, and on the same day the colliery manager sent for me and I met him. He did his best to get me to compromise, but I stuck to my guns. H had to pay each workman over twelve months’ back pay. This settlement reflected very badly on my Executive. Most of them were pilloried by the members over their decision to support me. However, when I reported my success at the next meeting of my Executive, they passed a resolution condemning me for defying them. There was considerable dissatisfaction among ordinary members over this resolution.

I now set myself the task of getting rid of the scheme under which workmen were paid compensation for injuries sustained during their employment. My first difficulty was to convince the Executive that the workmen would be much better off under the Compensation Act. I got a bare majority to get on with the job. We met the owners to discuss the subject. The air was tense and bitter. The owners knew that nearly half the Executive were against going under the Act. One of my worst handicaps throughout was that the Owners always knew our next move. After stormy negotiations, the owners caved in. The injured workers were overjoyed with the increases in the rates of compensation which followed this settlement.

Similar action was taken to restore the working of the 1912 Minimum Wage Act at the Collieries where it had been suspended. By now the membership was increasing gradually. This area is traditionally a non-unionist area. Add to this the fact the Union was never popular then it will be seen what an uphill struggle it was here.

It was around about 1924 that I went through a dramatic experience. The Miners’ Federation negotiated a National Wage Settlement. This settlement covered every district in the country, but true to form the coal owners in this district refused to conform to the terms of the National Agreement. I realised I had the stiffest fight on.

I reported the position to the Miners’ Federation. It took our case up with the National Owners’ Association but got nowhere. In the end, my Executive was invited to London to meet a joint meeting of the National Coal Owners and the MFGB. The local coal owners had been invited as well. The National Coal Owners declared it was a matter for the local owners, and the local Union to settle among themselves. Mr Arthur Cook met us in an adjoining room and gave us the decision. This looked like the end of our campaign. The Wembley Exhibition was on at the time. After the decision was made known to us, the Local Owner invited my executive to go with them to the Exhibition and then to have dinner with them. Most of them wanted to accept the invitation, but rightly or wrongly I advised against it.

At the next meeting that this course involved I proposed that we should take strike action. I knew this course involved a tremendous risk. Even now about half the workmen were out of the union. Only two of us on the Executive were in favour of taking this action, but the issue was taken to the lodges, and a majority of them decided to support the strike action. Notices were handed to the owners. On the day the strike started the workmen at three of the largest coalfields refused to strike. We organised a demonstration to one of the collieries. The workmen at this colliery were ashamed to go to work the next day. The next morning, we organised another demonstration headed by the town band to another colliery. This took place between five and six in the morning. After two days all the collieries were idle. On the second day of the strike, I was sent for by the Managing Director of the most up to date colliery in the district. No negotiations took place at our meeting. He simply announced that he was going to pay the workmen at his colliery in accordance with the terms of the National Agreement.

I convened a mass meeting of the workmen, and when I stated that I had made a settlement the crowd cheered madly. Nothing has happened like it in the history of the district. I made similar settlements at every other colliery in the district inside a week. I was asked to make these settlements myself by the mass meeting. The Executive was excluded from the negotiations. As a result of this strike the workmen got fifty thousand pounds in back pay; and they continued to enjoy the financial benefits of the National Agreement until the 1926 national strike.

In the meanwhile, I had another job to do but this time it was a job which involved the workmen as well as the Coal Owners. One of the largest collieries in the district know as Eastern United Colliery worked a system know as the Butty System. It was a vicious and wholly corrupt affair. Under it one man could exploit several of his mates. It was a paradise for back scratchers, but a wicked hardship for most colliers. The system was simple but very successful for the Coal Owners. One collier would be put in charge of several others. The Butymen would be paid on a price list while the colliers working for him would only get the District Minimum. Not more than a dozen workmen were in the Union at this colliery. No workman dared mention the union at this colliery. Most of the Buttymen were undercover agents for the management, and the managing director was as tough as they make them. However, there was a revival of goodwill among those colliers who were being exploited by the Buttymen.

We arranged to call a meeting of the workmen to consider the problem of the Butty System. To my surprise, the workmen flooded to the meeting. A resolution was passed to ballot the workmen on the system, and Mr Wallace Jones was appointed the executive member to represent the colliery on the Executive.

We held the ballot, and we had an overwhelming vote in favour of abolishing the system. As a result of his activities in organising opposition to the Butty System, he was sacked. I got him work at another colliery belonging to the same company, and in the meantime, he was appointed Check weigher at his own colliery, and throughout he gave signal service to the union of this district. The credit for this success belongs mainly to Mr Wallace Jones.

The colliery was like a prison before. Things changed drastically, after this, and the membership increased rapidly, and I was able to improve the conditions under which the men worked. For example, the workmen had to work in bad air. There was hardly enough air to burn a candle. One candle would last a whole shift. This state of affairs shortened the lives of miners tremendously. I was glad to get the chance to put this right. I brought the terms of the Mines Act to bear on the situation, and as soon we got the foul air removed from all the coal face.

The year 1926 arrived and by now the district was well organised. The personnel of the Executive had changed. Younger men had been appointed to it, and I was greatly helped by them. The strike started well for us. The workmen responded splendidly to their obligations. A host of dramatic events took place during that prolonged and agonising strike.

I shall cite one or two, or two, special experiences which represented more or less whatever was taking place during the strike. After about four months the miners were getting angry/. A few men at most of the collieries were going back to work. It happened that I had been instructed to invite Arthur Horner to the district to address a few meetings. In the meantime, the Executive was asked to hold a mass meeting of all the miners in the district and to form a demonstration to go to Cannop Colliery to meet the blacklegs coming out of the pit. Arthur Horner was at hand and he addressed the meeting with me. However, I suggested that I did not wish him to take part in this demonstration because I knew from previous experiences that it would be difficult to control the crowd, and I realised that he was not long out of prison himself.

The meeting was held at a centre called the Speech House. The colliery to which the demonstration was going was about one mile away. The crowd was very agitated, and I did everything I could to sober things up. I resigned myself to the idea that I would be arrested. The higher-ups in the police had been trying to get me for some time, and I was convinced that this was it.

We reached the colliery which was in the middle of the woods. There were several approaches to it. I looked for some members of the Executive so as to post them at the various approaches to the colliery, but some of them had disappeared.

The demonstration should have stopped outside the colliery premises, but instead, the crowd flocked onto the pit top and surrounded it. I went with them. I would like to say something that was noble and romantic about that demonstration. The last thing they wanted was to get me into trouble. Scores begged me not to go with them. They wanted to do the job themselves. The demonstration had arrived at the pit top about twenty minutes before the Blacklegs came up the pit. I was about to address the crowd when a police inspector approached me and said to me.

“This is an unlawful assembly, Mr Williams.” I said, “Yes it is.” I did not attempt to argue the point with him, I knew he was right. All I said was that I would do my best to keep the situation under control. While the Inspector was talking to me there was a prolonged hush. I then stepped onto a piece of timber and addressed the workmen. I told them that we had already broken the law, and I was personally responsible for what had happened. I asked them if they would agree to an idea I had put before them. I asked them if they would agree to let me, myself approach each blackleg as he came towards the main road leading from the colliery. They agreed to this idea but were disappointed as many wanted to set about the blacklegs.

As the first blackleg came forward I approached him and remonstrated with him. The same procedure was followed with each of them. There was a frightening silence, prevailing throughout.

After the last Blackleg had passed by, I announced the answers I had received from each of the Blacklegs. Most of the answers I received were favourable, and these were cheered loudly, and prolonged, but the unfavourable answers were booed much more loudly and bitterly.

I know expected to hear from the police about this unlawful assembly which had taken place. I gathered there had been a conference of the police on the affair, and though there could be no doubt that unlawful assembly could easily be proved, no action was taken.

However, this was the beginning of the end of the strike in the Forest of Dean. Nearly every day now I was called to most of the collieries to deal with men returning to work. The workmen had been out of work for over four months. They had not received a penny strike pay out of our funds. We had no funds. The only payment received by the workmen of this district was one payment out of what was described as “Russian Money”.

By the end of five months all the workmen in two collieries had gone back to work and a considerable number at the other collieries as well. Some of the workmen had no food to take to work, and were without any until pay-day. I managed to keep two large collieries idle to the end of the strike. The situation was a nightmare for me, and when it was all over, I had to start from the beginning again to organise the district.

In the thirties I moved a resolution at a National Conference asking the Executive to make an application for an increase in wages. Mr Joe Jones, the President told the Conference that it was not a suitable time to make the application. I pressed this demand home at subsequent conferences, and in the end, Joe Jones gave an undertaking that the Executive would look into the matter. An application was made and we got nine pence a day flat rate. It was the first increase in wages the miners had received since 1924.

The second world war came, and nothing very eventful took place in the Mining Industry until the war ended. Soon afterwards the mines were nationalised.

I would like to state that I was a member of the Miners Minority Movement throughout, and I received considerable help from Harry Pollitt, Nat Watkins and Arthur Horner.

I moved the first resolution at our National Conference to convert the old Miners’ Federation of Great Britain into one Union. This was done by the Minority Movement through my district which was associated with the Minority Movement/ I had no seconder for the motion. I moved the same resolution the following year. In the end the National Executive took over and formed the NUM.

I hope I am not too modest in mentioning something I did in 1923 or early 1924. The National Conference was discussing wages at Blackpool. I moved a resolution suggesting that we should ask the government for a subsidy to enable the industry to give the miners a badly needed increase in wages.

The officials scoffed at me, and the delegates ridiculed me, but one member of the National Executive was in favour of my idea, the revered Mr. Straker. The National Executive was under pressure from the districts on the question of increasing wages. After the conference the Executive was stuck.

A strike was risky, and so for Mr Straker told the Executive Committee that he thought there was something to be said for the idea. Roughly nine months from the date of the National Conference at Blackpool the industry received a subsidy of twenty million pounds.

I am sure that I fought the first case in which a claim was made to get compensation for Silicosis. The South Wales Miners Federation was the pioneer in getting Silicosis schedules under the Compensation Act. They spent thousands of pounds on the task. I put in a claim for compensation for a workman, on the day the schedule came into force.

Interview with John (Jack) Williams on 25 July 1963 by R. Page Arnot and Dai Francis. (Credit Richard Burton Archives)

On Friday the 19 July, I was driven by Dai Francis, via Newport (where we had a traffic hold up of half an hour) by Chepstow and up the bank of the Severn to the Forest of Dean. There we found Jack Williams, now aged 75. He was rather flustered at not having immediately recognised Dai Francis. But Dai raised him from his dolour by speaking in Welsh. Jack had not used the language for over forty years but he responded slowly but correctly. His face gradually lit up.

Re-calling the past, he said there had been an SDF in the Gawr Valley and, of course, in the Rhondda. Moth Jones who died in 1961 aged 84 had been a pioneer. There was also Watkin Wynn. The first conference he attended was held long ago in Nottingham. He was a delegate along with Frank Hodges, then the agent for the Gawr. There was an incident of Hodges with a girl in the hotel. It was the first time he had ever imagined such a thing could take place.

He knew Ramsey Macdonald personally, had walked with him at the time of the TUC at Bournemouth. A majority of the Labour MPs were willing to go with Macdonald in 1931, Such people particularly as Shinwell was “a lickspittle.” He remembered Ernest Bevin after Shinwell had made a speech getting up and shouting out thrice “Dirty Shinwell”. I t was Arthur Henderson and the General Council who pulled the Labour members back from following Macdonald. “When afterwards you heard Shinwell and others attacking Macdonald, and you know this, it made you think much less of them.”

His main interest at the moment was to think out ways of combating the danger represented by the Catholic Church.

I had explained at the beginning that in writing to Dai Francis I had suggested that if we had to be in the Forest of Dean we should call on an old friend. He said he was greatly honoured. He also told how when on the Executive he had conceived a high regard for the honesty of outlook and expression of Dai Francis

Death

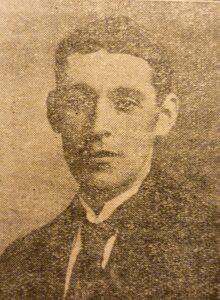

Williams died on 15 March 1968 three years after the last deep mine in the Forest of Dean was closed. His obituary in the Lydney Observer reveals a man whose contribution to society was extensive:

We have received some further details of the life of Mr John Williams who rendered distinguished service to the miners of the Forest of Dean during the 30 years he was their agent, and who died at the Dilke Memorial Hospital on Wednesday of last week. Mr Williams had been present at the foundation of this hospital and had rendered years of service to it and the Gloucester Royal Infirmary. Many years later, as a patient in both hospitals, he was grateful for the excellent nursing given to him.

During his life, he was responsible for many reforms. Before the existing National Health Service, he organised a pilot scheme in South Wales, which anticipated to some extent the benefits enjoyed today. It is believed that he was solely responsible for establishing the means by which miners could convalesce by the sea, a unique experience for many of them. His work at the Gloucester Court of Referees was particularly successful owing to his innate ability to put the points at issue, difficult though they often were, in clear, simple language.[3] For this reason, he will be remembered with gratitude by many ex-miners.

In many spheres, he was ahead of his time. He knew both Sylvia Pankhurst and Annie Besant and was an active supporter in the agitation to get women the vote. On one occasion he was struck by a baton during a Trafalgar Square demonstration. He was a lifelong freethinker and was not afraid to offend the religious susceptibilities of his contemporaries. His activities in the political and trade union movements brought him into contact with many colourful personalities including the young Jeanie Lee and Aneurin Bevan, Sir Stafford Cripps, Sir Richard Ackland, James Griffiths, Hewlett Johnson the “Red” Dean of Canterbury and Professor J. B S Haldane.

Although a left-winger in the Labour movement, he admired and liked Ernest Bevin and considered Ramsey Macdonald to be head and shoulders above other labour leaders in intellectual attainment and defended him under attack. An admirer of Churchill’s speeches, he shared with him his love for Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”. As a young boy, he would travel from South Wales to London to see the first performance of a play by Bernard Shaw and until his last illness kept his love of the arts.

Through all his vicissitudes he was loyally supported by his wife Margaret, who was of invaluable help to this remarkable man. Cremation took place at Cheltenham on Saturday morning. Mourners were Mr Dennis Williams (son), Mrs Margaret Nest Sinnott (daughter), Mr Emyln Williams (brother), Mr David Jones of Pillowell and close associates. The service was conducted by a member of the Cheltenham Humanist Society.