“The world would be better in many ways if there were more people like Charlie Mason.”

(John Williams, agent for the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association, 1945.)

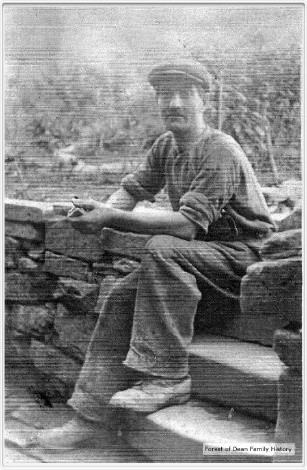

Charlie Mason was a Forest of Dean miner, a much-loved husband, father and son and a popular and respected member of his community. He was known for speaking up on behalf of his fellow workers and actively participating in public bodies within the Forest of Dean.

However, as Ralph Anstis observed, Charlie was “curiously shy” and uncomfortable with public speaking.[1] As a result, he seldom appeared on public platforms alongside the more prominent leaders of the Forest of Dean labour movement, whose names frequently featured in local newspapers between the 1920s and 1940s.

Despite occasional reports in local newspapers, the lives of people like Charlie Mason often remain hidden from history. However, it is important to recognise the role of miners like Charlie whose daily conflicts over health and safety, piecework rates, victimisation, and unseen bullying in the depths of the colliery provided the backbone to the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association (FDMA), the main trade union representing Forest of Dean miners.

In the case of Charlie, this changed long after his death with the publication of the books A Child in the Forest in 1974 (reprinted as Full Hearts and Empty Bellies in 2009) and No Pipe Dreams for Father in 1977 by his daughter, Winifred Foley.[2] These were followed by her books Great Aunt Lizzie in 2002 and In and Out of the Forest in 2009.[3]

This article will draw on Winifred’s work to provide some background to Charlie’s life. In addition, it will utilise local newspaper reports to highlight his interventions on behalf of his fellow miners during the 1926 lockout. It will focus mainly on his role at the meetings of the Westbury Board of Guardians whose job was to provide Poor Law relief to the destitute families of miners. The article then traces his life in the years that followed the lockout and finally his tragic death in a pit accident in 1945.

Thanks to Charlie’s grandson Clive Mason and granddaughter Margo Woodhill for sending information, memories and photos. Thanks for the support from Winifred’s daughter, Jenny Townsend. Thanks to Paul Mason, a distant relative whose family lived very close to Charlie, for information and stories. Also thanks to Nicola Wynn and Jason Griffiths from the Dean Heritage Centre for help and advice.

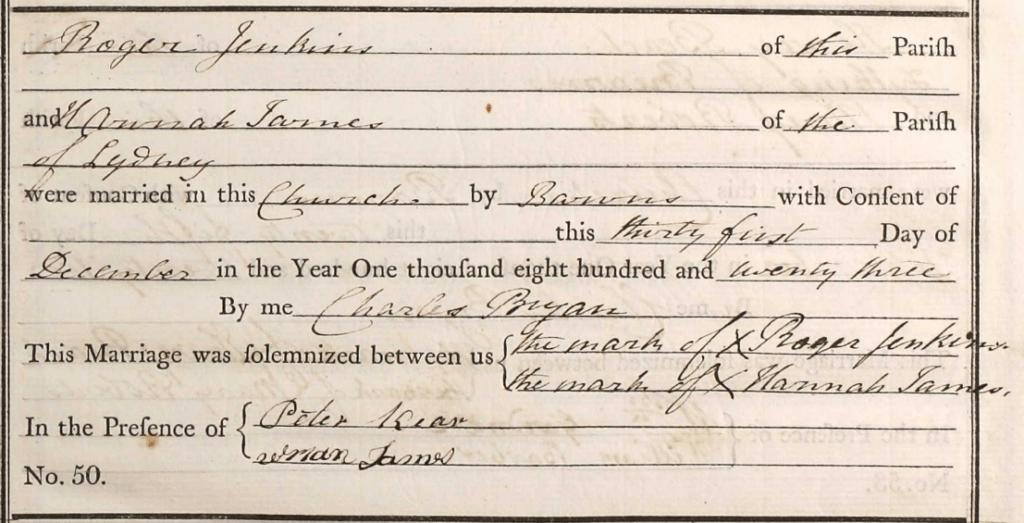

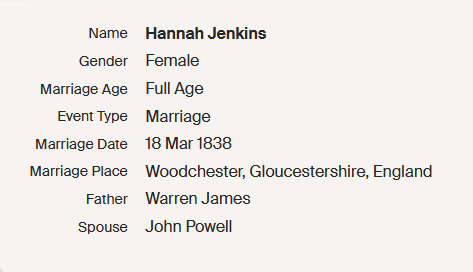

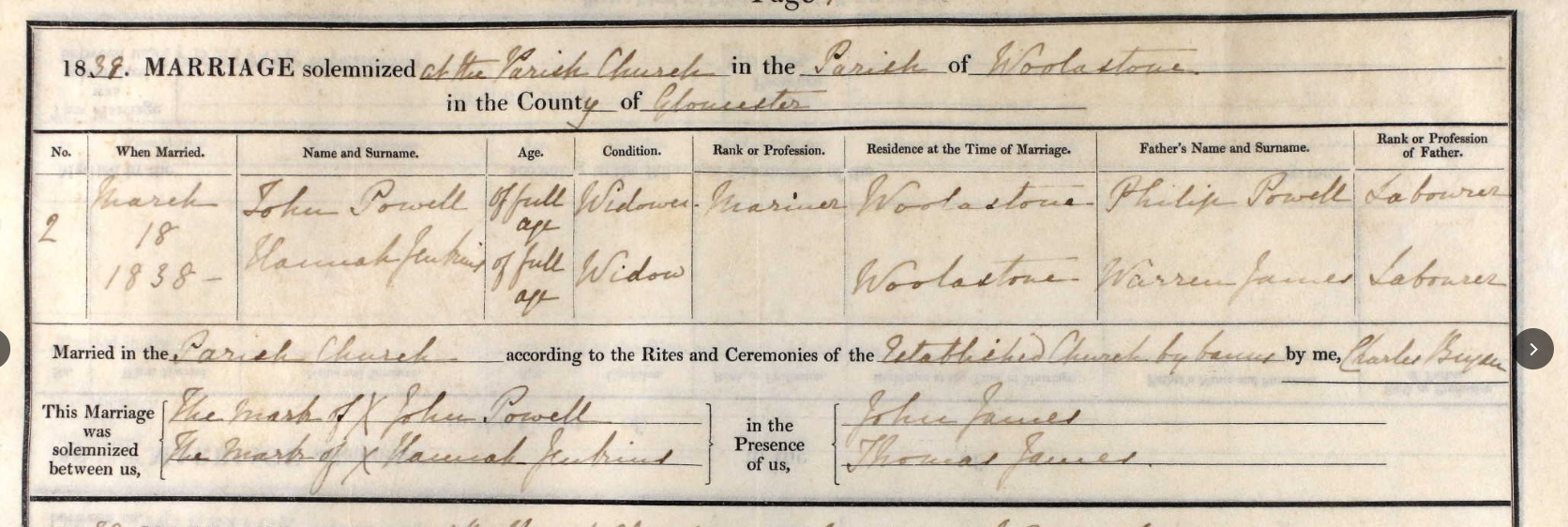

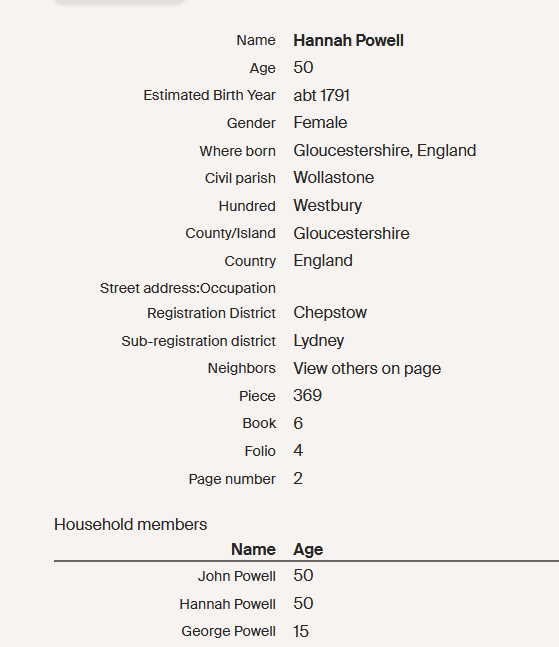

Early Years

Charlie Mason was born on 9 August 1889 in Brierley, a small village in the north of the Forest of Dean. He descended from a long line of Masons who lived in Brierley and worked in the local mines and quarries. The houses on Brierley Banks, where Charlie lived, were small and in poor condition, and lacked indoor toilets. While most have since been demolished, the house Charlie’s family lived in, Roslyn House, still stands.

Charlie attended the Slad school in Ruardean Woodside and started work in the mines at the age of eleven. He initially worked as a hod boy for his stepfather, Robert Penn. In her book, In and Out of the Forest, Winifred Foley said:

Less than a century ago little boys of ten or less followed their fathers down the pits as hod-boys, as my own father did at the age of eleven. A chain around his waist and between his legs was attached to a cart, so he dragged the coal that his stepfather had pickaxed out to the bottom of the shaft. It was rare indeed that they worked in a place high enough to stand in.[4]

Winifred added that Charlie’s Great Aunty, Lizzie Mason, told her:

Charlie, your Dad, was only 11 years old when he had to go to work in the pit as hod boy to his stepfather….”Being hod boy was a terrible job for a boy his age but he never grumbled. His stepfather was a miserable sort but not a bad man. I can only remember him acting wrong once. Them days the men was paid 3d a ton for all the coal they could send to the face. It was hard luck if they got on a bad seam with stone in it. One time they was on an awful seam, nearly all stone and they got nothing for that. At the end of the week, your Grancher had only got 4 shillings and 3 pence wages to come.[5]

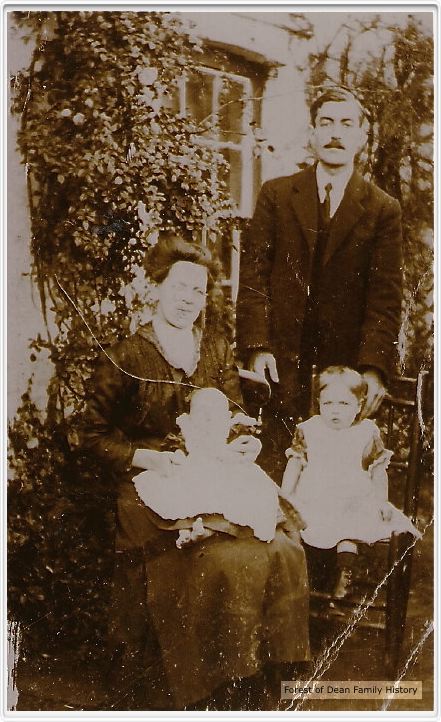

When Charlie was about twenty, he became unemployed and so walked to South Wales to work in its coalfield where he met his future wife, Margaret Daniels. The couple married in 1909 in South Wales and soon after they moved back to the forest to live with Charlie‘s Great Aunt Lizzie “who had always loved him like a son”. Their first daughter, Bess, was born in 1910 but sadly Charlie and Margaret lost their next two children soon after they were born.[6] Work was hard to come by so Charlie had to return to work in South Wales. Winifred, who was born in July 1914, recalled:

Dad walked to Wales and got a job in the “Six Bells” colliery near Abertillery. This time he lodged with Mam’s oldest sister Polly, who had married a man much older than herself and was childless. She only took a pittance off Dad for his keep, but even so, he could not afford to come home when Mam gave birth to me.[7]

World War One

Soon after, the war broke out in August 1914, Six Bells temporarily closed due to a lack of manpower. Charlie returned to the Forest and the family moved into a family cottage in Brierley with Charlie’s great Aunt Lizzie. Charlie got a job at a nearby pit, probably Trafalgar colliery. The couple went on to have four more children, Dick, Sidney, Gwen and Marie. Sadly, Sidney died when he was just 16 months old. The children and parents were devoted to each other:

To us children our Dad was the fount of wisdom, kindliness and honour. Whenever we wanted his attention he became a child among us — slow, dreamy and always understanding.[8]

At the start of the war, some miners volunteered for the military but the more experienced miners like Charlie, now aged 25, were encouraged to stay in the pits where their skills were in great demand to supply coal for the war effort. Winifred remembered her dad saying:

Plenty o’ work in the factories making armaments an’ uniforms for men to die in. Seems there’s nothin’ like a few years o’ ’uman slaughter to get the economy going.’ [9]

The work was hard and miners were expected to work long hours flat out, with no holidays, to maintain coal supplies for the war effort. Charlie did not approve of the militarism and jingoism that was widespread at the time and told Winifred:

The German men be the same as we men. Like us they ‘ave swallowed all the propaganda put into their ‘eads by the big powers that do rule us all. ‘Tis to keep the power and wealth that is in this world for themselves that countries do fight each other, and the people do swallow it all, put on uniforms and go murderin’ each other by the thousands. The hate is whipped up by such tales as you two ‘ave listened to. No doubt German women is swallowin’ the same tales ’bout we Englishmen! [10]

Cannop

When the war came to an end, the pressure on the miners to increase productivity continued because of a shortage of labour. At some stage around this time, Charlie became very ill with pneumonia but recovered. Winfred believed:

That illness, we always believed, came from the conditions in which he worked when he was forced to go to a pit three miles from home. He was sacked from the pit near the village after the owner heard of his radical views and told the manager to get rid of him. The walk to the new pit wasn’t too bad — it was downhill most of the way — but it was a hard grind home for an exhausted man at the end of a long shift.[11]

This was probably Cannop colliery because, in 1919, Charlie was working at the pit which was about a one-hour walk from his cottage in Brierley. Charlie was soon elected as one of the Cannop delegates on the Executive of the FDMA. He joined the campaign for the nationalisation of the mines, a pay rise and reduced hours for miners. There were strikes but, after a few months, the miners accepted a seven-hour working day and a pay rise which kept up with the rising cost of living. However, the government refused to accept a recommendation from a Coal Commission to nationalise the mines. Charlie was now becoming more involved in politics and became a committed and active member of the FDMA. Winifred wrote:

If they were not at the pit, Dad and a couple of cronies would be arguing nineteen to the dozen about religion, politics, science, economics, or the fourth dimension. There they sat on their threadbare behinds putting the world in order. [12]

If he had a fault, it was the spending of sixpence on a book while his ragged shirt tails were hanging through the ragged patches of his moleskin trousers. He loved to discuss his reading with his cronies. The fireside talk we overheard between them was full of H. G. Wells, Einstein, God, Darwin, Shaw and Lenin.[13]

1921 Lockout

In 1921, the government and the owners responded to a depression in the coal trade by a proposal to radically reduce labour costs, which, in the Forest of Dean, translated into wage cuts of up to 50 per cent. The miners refused to go to work under these new terms and downed tools. As a result, on 31 March 1921, one million British miners were locked out of their pits including many war veterans and over 6,000 miners from the Forest of Dean.[14]

Charlie joined Frank Matthews and William Hoare as representatives of the Cannop miners on the FDMA Strike Committee. Charlie probably supported the decision of the FDMA and the Cannop miners to refuse to allow safety men to enter the pit to operate the pumps to prevent flooding. They hoped this would put extra pressure on the colliery owners to settle the dispute.

Cannop normally employed 36 men pumping two to three thousand gallons a minute to keep the level of the water down in the pit. After the withdrawal of the safety men, the colliery was completely flooded and the management warned the pit may not re-open due to permanent damage.[15] Winifred was only seven during the strike but remembers miners confronting blacklegs at Waterloo colliery near Lydbrook:

I do remember once playing with older children watching for blacklegs going to work at Waterloo. We hid in the bracken, and when we saw them, we slipped away and told the men on strike in the village. They hurried off to meet the blacklegs and shout abuse at them.[16]

The lockout ended after 12 weeks when the MFGB advised the men to return to work and accept the reduction in pay. The concerns about the flooding at Cannop causing permanent damage proved unfounded and, once the miners got the electrical equipment re-installed and the pumps running again, Charlie and his mates were back at work.[17]

Religion

One of the consequences of the lockout was that Charlie became more radical in his views: Winifred wrote:

Over the years the ways in which the miners were treated turned him into what people call a socialist or some say, communist. It can’t be a bad thing, for if you read the Bible, the Lord himself was against the rich and the greedy and they hounded him to the cross for it.[18]

After 1921, many miners felt abandoned by the church and established society and this turned many away from religion. Winifred remembers:

I’d heard him and his butties argue and come to the conclusion that there couldn’t be a God, or at any rate not one who worried about us as individuals.[19]

He never went to chapel, and indeed held the opinion that in general organised religion was the opium dealt out to the masses by the cynical few, to obtain for themselves their own heaven on this earth.[20]

East Dean District Council

Charlie became an active member of the Labour Party and in 1922, he was elected to represent the Drybrook ward on East Dean District Council which was chaired by George Rowlinson.[21]

In this role, Charlie worked closely with one of the other Labour councillors, Tim Brian, who worked as a deputy at Cannop. Brain had been elected onto the council in 1919 and at the same time, he was elected as a member of the Westbury Board of Guardians. In 1922, Brain was elected as a County Councillor for Drybrook and was described by the Dean Forest Mercury as belonging to “the extreme section of the Labour Party”.

These two men became good close friends and political allies. Their focus was on fighting for the rights of the poorer people in their community. In April 1923, the Dean Forest Mercury reported that:

A motion was brought forward that the Council consider the question of wages unskilled labourers are paid by the Council, the mover being Mr. C. E. Mason with Mr. T. J. Brain seconding. An amendment referring the matter to the Finance Committee was, however, passed. It was stated that the present wage was 36s per week.[22]

Westbury Board of Guardians

The Boards of Guardians, who administered the Poor Law, were made up of elected representatives. The Guardians had the statutory responsibility to provide relief to the destitute in the form of accommodation in a workhouse or outdoor relief in cash, vouchers or a loan. However, this only applied to the physically fit men if no work was available. The local parish authorities collected the money required to fund the Boards of Guardians from the rates (a tax on property).

In 1923, Charlie (age 35) was elected as a Poor Law Guardian on the Westbury Board of Guardians which was responsible for providing relief to the destitute in the East Dean area. The destitute living in the West Dean area were required to apply for relief from the Monmouth Board of Guardians, those living in Ruardean had to apply to the Ross Boards of Guardians and those living in the Lydney area had to apply to the Chepstow Board of Guardians.

There were approximately 35 Guardians on the Westbury Board, although not all of them could attend every meeting. This was a particular problem for Charlie as he worked shifts and so was not able to attend all the meetings. Charlie immediately came into conflict with some of the older members of the Board who represented the interests of the establishment. In particular, he often clashed with the chair, George Rowlinson.

Rowlinson was the FDMA agent from 1888 to 1918 and had been a member of the Liberal Party but now sat as an independent. In the period before the war, Rowlinson had opposed attempts by the FDMA to affiliate with the Labour Party. He was finally voted out of office in 1918 over his support for the conscription of miners, failure to support his members during industrial disputes and his opposition to the Labour Party. As a result, he was hostile to the existing leaders of the FDMA who were instrumental in getting him voted out of office.[23]

However, Rowlinson had the support of most of the members of the Board, who were mainly senior members of the establishment. In contrast, Charlie could only rely on the support of the four other Labour members. In March 1923, the Western Mail reported the following confrontation when Charlie was rudely interrupted by Rowlinson and other Board members:

Mason remarked he had no more sympathy with a man in the higher walks of life because of his position than he felt for one of the ” submerged tenth.” He went on: “If the Duke of York…”

The Chairman: “No, no. The Duke of York has nothing to do with it. He is not before us.” A chorus of members joined the chairman’s protest against Mr. Mason’s remark.[24]

Charlie was keen to represent the interests of the workhouse residents but often got a hostile response from Rowlinson. In November 1924 the Gloucestershire Echo reported:

Mr. C. E. Mason, at a meeting Tuesday of the Westbury-on-Severn Guardians, reported that some of the old men had confided in him that for more than a month both meat and bread were deficient as to quantity and quality, whilst vegetables – potatoes chiefly – had been scarce. Mr Mason suggested the complaint deserves an inquiry. Three old men—one on crutches—came before the board, and bore out Mr Mason’s statement. The Chairman (Mr G. H. Rowlinson) and several guardians said that such a serious complaint could not be allowed to pass unchallenged, and at the Chairman’s suggestion the house committee was instructed to hold an inquiry. The Chairman said that he had himself dined off the ordinary menu, which ought to satisfy anyone.[25]

In the end, an enquiry concluded that the food was adequate.

1926 Lockout

In early 1926, the British colliery owners announced they wanted to end the existing national agreement, cut wages and increase hours. On 1 May 1926, having refused to accept an increase in hours and a reduction in pay, one million miners across Britain, including nearly 6500 miners from the Forest of Dean, were locked out again.

Opening with the heady days of the general strike, the miners’ lockout of 1926 was a pivotal moment in British twentieth-century history and it continued for seven months. In the Forest of Dean, where coal mining was the main industry, its impact was profound and poverty and destitution became widespread.

Merthyr Tydfil Judgment

As a result of a legal ruling made in 1900, called the Merthyr Tydfil Judgment, striking miners were not considered by the authorities to be destitute because they were deemed to have refused work. However, their dependents such as wives, children under fourteen and widowed mothers could be helped with an allowance if they were in severe need.[26] At the start of the General Strike, the FDMA suggested miners should go to the Boards of Guardians to claim Poor Law relief and argue they were not on strike but locked out and destitute.

The Ministry of Health issued a circular recommending that Boards should abide by the Merthyr Tydfil Judgment. The circular added that any money coming into the house from other sources such as donations, working children, pensions or savings could be deducted from the weekly allowance. The families of miners who owned or were buying their property with a mortgage were also disqualified from relief.[27]

The use of the Poor Law powers during the 1926 lockout varied considerably from region to region and the most significant factor influencing a particular Board’s policy was its political stance. In some districts, the Labour members were in the majority on the Boards and argued that the Merthyr Tydfil Judgment ruling was ambiguous because it ignored the statutory duty to provide for all those who were destitute. In addition, there was a question mark over whether the judgement applied to the 1926 dispute because some argued that the colliery owners had broken the terms of a national agreement and so the miners were not on strike and refusing employment but were locked out.

In Durham, Yorkshire and South Wales, some Boards applied for loans to cover extra costs and were able to provide relief to some single miners during the lockout and were relatively generous with the amount they paid out to the wives and children of miners. However, in the Forest, where Labour members were in a minority, most of the guardians insisted on a strict interpretation of the rules and the recommendations in the Ministry of Health circular. They argued that work was available and there was no difference between a locked-out miner and one on strike.

Consequently, in the Forest of Dean, no outdoor relief was available to able-bodied single men or married men. The ruling proved to be particularly harsh on single men who were left with no income. If single men lived in lodgings or with family members, they became dependent on the families with whom they lived, adding an extra burden to those households.

The Labour members on the Boards in the Forest of Dean did their best to challenge the legality and morality of the decisions made by most of the Board members, most of whom were from upper or middle-class backgrounds. Some Board members like Rowlinson, were well-versed in using legalistic arguments and bureaucratic manoeuvres to undermine those Labour members who were less knowledgeable or experienced.

In some respects, the battles fought by the Labour members on the Boards of Guardians were as important as those fought on the picket lines. Without a regular income from the Guardians, it was unlikely the miners could resist the temptation to return to work.

The lengthy debates at the Board of Guardians were often recorded word for word in the local papers, including the many disputes over the attempts by Board members to reduce the allowance and whether the award was issued as a voucher, in cash, or as a loan. Consequently, it is possible to summarise the debates and reproduce some of the exact words spoken by Charlie during his fight to defend the interests of the Forest of Dean miners in 1926.

Westbury Union

In 1926, Labour Party members on the Westbury Board included Frank Ashmead, William Ayland, Abraham Booth, Tim Brain, Harry Morse and Charlie Mason. Ayland was a general labourer from Westbury-on-Severn. Morse was a collier from Blakeney who worked at New Fancy colliery. Booth worked as an insurance agent for a Friendly Society and Ashmead worked as a clerk at Cinderford cooperative bakery. Mason and Morse were now locked-out miners. Brain, who was a colliery deputy, continued to work at Cannop to prevent flooding and help maintain the pit.

Most of the remaining 30 members of the Westbury Board were senior members of the establishment. Most owned their businesses as shopkeepers, tradesmen or farmers and nearly all were employers. Two were members of the aristocracy. They were vehemently opposed to the action of the miners in refusing to accept a reduction in wages and an increase in hours.

The chairman, George Rowlinson, who had fallen out with the FDMA and was hostile to the miners, sat as an Independent. Ashmead was an ex-miner who had worked closely with Rowlinson when he was the agent for the FDMA and, out of loyalty, he often backed Rowlinson up in the meetings.

John Williams

On Friday 7 May, there was a long queue of miners outside the office of the Westbury relieving officer for the Cinderford area, who was registering applications for relief. Consequently, by mid-May, the Westbury Board had received over 700 applications from the families of miners. On 11 May, an emergency meeting of the Westbury Board met to discuss how to deal with the requests for relief.

In response, John Williams, the full-time agent for the FDMA from 1922 to 1953. worked with Charlie to organise a demonstration to pressurise the Westbury Board to provide adequate relief. As a result, a large contingent of East Dean miners and their families walked or cycled to Westbury-on-Severn to lobby the Board meeting. At the beginning of the meeting, the Board agreed that they would receive a deputation from the demonstration to hear their case when they had finished their discussions.

During the discussions, Rowlinson said it might take a week to deal with all the applications and each case would be considered on its merit. After a long discussion, it was agreed that relief could only be offered to women and children and a weekly allowance of 10s for a miner’s wife, 4s for a first child and 2s 6d for other children up to a limit of 25s was decided upon. The relief would not be a loan and they would receive the allowance of 25 per cent in cash and 75 per cent in vouchers to be exchanged in local stores. The relief would be granted for only two weeks after which the cases would be reviewed. This amount of relief was less than recommended by the Ministry of Health and less than provided by some other districts.[28] Mason volunteered to join eight other Guardians on a relief committee to meet in Cinderford to consider further applications for relief and to grant relief according to the above scales.[29]

Throughout the meeting, there was some tension between Rowlinson and Charlie, who did his best to argue in the interests of destitute families and single men. At one point, Charlie correctly challenged Rowlinson’s claim that the law said that destitute single miners could not even be admitted to the workhouse.

The attitude of some of the Guardians appeared to be that the money belonged to them as ratepayers and they were donating it to the mining families out of charity. During the discussion, Charlie made the point that the miners were part of the community too and paid rates and so were entitled to benefits as of right in time of need. Daniel Walkley, who ran a transport business in Cinderford, and J. S. Bate, an estate agent from Blaisdon, claimed that their duty was to the ratepayers and that the young single miners could not be destitute because work was available to them. The Dean Forest Mercury reported Charlie’s reply:

Where? …As the youngest member of the Board, he understood his duty quite well and was not going to Mr Walkey to learn it. He was representing the public, and a most essential part of the public. The miners were in the public area. He took it that young men also put money into the fund for administering the Poor Law.[30]

Charlie went on to argue that the Board’s duty was to consider the destitution of members of the community when assessing if relief should be provided without prejudice. He added that the Ministry of Health had stated that the Guardians should not take sides in industrial conflicts which it appeared as if they were doing.

Williams and Thomas Etheridge, the full-time financial secretary of the FDMA, were then invited into the meeting as representatives of the delegation. They presented a case for relief for all miners, particularly the single men, arguing that it would be humiliating for them to enter the workhouse. He added that another vulnerable group was made up of those who owned their houses or were paying a mortgage as they were in danger of losing their property if they could not keep up payments. He asked for relief to be paid wholly in cash to prevent exploitation by tradesmen.[31]

When addressing the crowd of miners and their families outside after the meeting, Williams reported that the Board had decided that the cases of able-bodied single men would not be entertained but, if completely destitute, they may be allowed a bed in the workhouse. He reported the cases of house owners would be considered on merit and any money received from the MFGB or elsewhere would be deducted from the allowance. The relief would be paid out at Wesley Hall in Cinderford on Saturday mornings. Williams added:

I want to acknowledge we owe the Board of Guardians something for the courtesy they have shown us this morning.[32]

Loan

At a meeting of the Westbury Board held Tuesday 25 May, the Guardians were informed by the finance committee that by the end of next week the Board will be about £6000 overdrawn so it would be necessary to arrange an overdraft with the bank. They added the precepts from the local authority due to them as their share of the money collected from the rates was due 1 June but it was unclear if they would receive them. The use of overdrafts and government loans to Boards of Guardians, during this period, was widespread and some other Boards were far more heavily in debt.

As a result, the Finance Committee presented a motion that stated that from now on the grant should be in the form of a loan and reviewed every week. In response, Charlie argued that:

He could see no reason why the grant should be in the future in the form of a loan. He thought the subject was carefully considered last week and he did not know what the prospects were of return even if they did grant it on loan. It seemed to him more or less a farce because the people were destitute and knowing the district very well, he could not see what chance of their paying the money back.

Charlie argued that East Dean was more disadvantaged than other districts because the house coal pits in East Dean often only worked part-time. However, when it came to a vote, Charlie only got the backing of four other Labour Party members while Rowlinson, Ashmead and the others voted in favour of the finance committee motion. It was also agreed that the Board should meet every Tuesday while the present emergency lasted.

Charlie vs Rowlinson

On Tuesday 1 June, the Westbury Union met again and the Guardians were informed that a meeting of the Finance Committee had produced a report which recommended that relief for the first child should be reduced from 4s to 2s 6d. Rowlinson then informed the meeting that a resolution had been passed at the Finance Committee that the allowances would be fully awarded in the form of vouchers. Booth complained about this decision but was overruled by Rowlinson who claimed the conditions had changed.

Charlie argued that the resolution about the vouchers had not been agreed upon at a full meeting of the Board and challenged Rowlinson over the undemocratic way the decision had been made. He then moved a motion, seconded by Booth, that the decision be rescinded. Rowlinson replied that he needed seven days’ notice to accept a motion to rescind a resolution. Charlie attempted to respond but was told by Rowlinson that he had spoken more than once and he should “not strain the feelings of the Board”.

After more discussion, Charlie moved an amendment that the allowance for the first child remains at 4s. However, the motion was defeated with twenty-two against and only Labour Party members (Charlie, Abraham Booth, Harry Morse, William Ayland and Tim Brain) voting in favour. At that point, the atmosphere became quite tense when it appeared that Charlie accused Rowlinson of lacking courage. Rowlinson replied, “I don’t allow you or anyone to tackle me on my courage.”[33]

Finally, Brain presented a resolution, seconded by Booth, that the families of miners whose property is mortgaged should also get relief but this was defeated with 11 votes in favour and 13 against.[34]

Cinderford

On Tuesday afternoon 8 June a meeting was held at Cinderford Town Hall with Enos Taylor in the chair. Taylor was a locked-out miner who worked at Foxes Bridge colliery. He said the main purpose of the meeting was to protest against the decision of the relieving officers to deduct money from the loans to those on relief, on the assumption that they had received money from the MFGB donated by the Russian miners.

Williams said he also wanted to protest against the decision of the Westbury Board to reduce the allowance for the first child and provide relief solely in the form of vouchers. He pointed out that the vouchers were provided only for food and did not cover other necessities like medicines. In addition, he argued that the families of miners who owned their own houses needed help too. The Dean Forest Mercury reported that Williams:

Thought it was only fitting that he should read the names of the five persons who had displayed with courage and remained so loyal to them in the discussions at the Guardians as reported in the “Mercury” – Mr Morse of Blakeney; Charlie Mason – who was putting up a very vigorous fight indeed (applause) – Tim Brain, Abraham Booth, and William Ayland (applause). These were five persons who had been standing up in the interests of everybody.[35]

Williams argued that they needed to make a protest or the Guardians would continue to reduce the allowances. He argued that there may have to be an increase in the rates to cover the cost and felt that most people in the community were prepared to make this sacrifice. A resolution of protest against the action of the Westbury Board in reducing the allowances was proposed by Joseph Holder and seconded by Jack Harris, both locked-out miners, and passed without dissent.[36]

Bureaucratic Manoeuvres

On Tuesday 8 June, the Westbury Board met again and Rowlinson continued to use bureaucratic manoeuvres to undermine attempts by the Labour Party members to challenge his authority. He reported that some traders had complained they had lost custom because most of the people receiving the vouchers were exchanging them at the Co-operative Store. As a result, Charlie put forward a motion that 25 per cent of the allowance be in cash to give those receiving relief more choices. However, this motion was disallowed by Rowlinson.

Booth then presented a motion that applicants could receive an extra allowance to cover rent and mortgage interest repayments and that families owning their own houses should be eligible for relief. Rowlinson refused to accept the motion, arguing it needed to be tabulated in the correct form and given to the clerk to be presented at the next meeting. Charlie asked if families needed to travel to Cinderford to make a new application every week. Rowlinson argued it was not possible to make any changes because the Board had already passed a motion to grant relief one week at a time.[37]

Co-operative Society Membership

Most miners living in Cinderford were members of the Cinderford Co-operative Society, which was very much part of the labour movement in the Forest. Cinderford Co-operative Society, just like other Co-operative Societies in the Forest of Dean, was run and managed by its members in the interests of its members, mainly to provide relatively cheap food. In Cinderford where eighty per cent of the population were miners, the management committee included some miners.[38]

The hostility of some members of the Board towards the miners was highlighted at the next meeting of the Westbury Board on Tuesday 15 June. Rowlinson had discovered that members of the Co-operative Society in Cinderford needed to hold a maximum of three pounds in their account to maintain their membership. If the amount dropped below this then they would lose the benefits of membership. Rowlinson claimed that Co-operative Society members could not be classed as destitute as they had £3 in savings and therefore were not entitled to relief. Charlie responded by presenting a motion, seconded by Ayland, that the Board consider such cases as destitute. However, Charlie was forced to withdraw the resolution on being told by Rowlinson that the Board was legally obliged to strictly follow its rules on savings.[39] In contrast, most other Boards of Guardians in mining areas were far less rigid in their interpretation of the law.

Following this, one of the Labour Party members, Harry Morse, explained that under the existing system, any money coming into the house was deducted from the allowance which had a maximum of 25s. He proposed that in future in a house with four, five or six children then if 12s were going into the house in income from other sources this should now be ignored. Likewise, 9s should be ignored if there are three children and 7s if there is a wife and child. He presented a resolution to this effect which was seconded by Booth and Charlie.

Charlie spoke in favour of the motion adding that it was wrong that war pensions were being deducted from the allowance. However, Rowlinson told Charlie he could not speak again. When the motion was put to the vote it lost with only the four Labour Party members present voting in favour.[40]

The Labour Party members continued to make a stand. On 22 June, Booth put forward a motion, seconded by Mason that the decision to pay allowances in kind made on 25 May should be rescinded, but was lost with only the five Labour Party members voting in favour. Similarly, a motion presented by Booth and seconded by Mason that “an allowance be given to cover rent” was also defeated.[41]

No More Relief

By mid-July, about 750 families were receiving relief, in the form of loans, from the Westbury Board of Guardians. On 17 July 1926, the number of persons receiving domiciliary Poor Law relief, from the Westbury Board, including women and children, was 3,677.

On 3 August, the Board decided by a small majority to cut off all relief to miners’ wives and children, arguing that since some pits were open, work was available to them. The motion was presented by Mr Blanton and seconded by Mr Boughton and stated that:

Relief orders shall continue for this week and then cease. [42]

The motion was passed with ten in favour and five against. Charlie and the other Labour members pointed out that as far as they knew, Westbury was the only Board in the country to cut all relief to the families of miners. However, Rowlinson and his supporters on the Board refused to listen.[43] Tim Brain was shocked and:

appealed to the Christian men: Did they want the country built upon slavery? It was not Christian If men wished to force them to that. They talked about relieving the miners, but it was their wives and children they appealed for. But if they were, they were not dealing with cowards, but with men who had stood all these weeks on empty stomachs for what they thought right.[44]

The decision of the Westbury Board of Guardians was highly controversial and possibly illegal because Guardians had a statutory duty to provide relief to the destitute, provided they were not an unemployed man for whom work was available. The only other Board of Guardians to take such extreme action in the summer of 1926 were Bolton at the end of July and Lichfield on 3 September. This had a significant impact on the course of the lockout in the Forest and achieved its aim of driving some miners back to work.

Purcell

As a result of the decision of the Westbury Board of Guardians to discontinue relief to miners’ families, Alf Purcell, M.P. for the Forest of Dean, wrote a letter to Chamberlain, the Minister of Health in which he said:

I draw your attention to the matter of the Westbury-on-Severn Board Guardians in connection with their refusal of outdoor relief to miners within the Westbury Union. As far I can gather, the Board has, in effect, stopped outdoor relief to all except those who have applied for work at the pits and been refused. (in reference to men applying for work at pits where some men have resumed employment).

Further, if my information is correct, it would appear clear that the Westbury-on-Severn Board are not carrying out their duty set forth in the circular referred to by Sir Kingsley Wood, in the House of Commons on Thursday, July 22, and set out on page 1,560, Parliamentary Debates, follows:

The function of the Guardians is to relieve destitution within the limits prescribed by law, and they are in no way concerned with the merits of an individual dispute, even though it results in applications for relief. They cannot, therefore, give any weight to their views in dealing with the applications made.” Again, on page 1,674, Sir Kingsley Wood stated: “But where on the one hand we have case like West Ham, or the other hand case like Lichfield, both at opposite ends as it were the matter which we are discussing, then it is properly—as I think the House will agree—the duty of the Ministry of Health to see that the law is complied with.”

I need scarcely assure you that the position is a rather serious one calling for urgent attention, and I shall feel ever so much obliged if you will give your immediate attention to the whole matter.[45]

In response, on 11 August, the FDMA organised a mass meeting of miners and their families in Cinderford, where Williams argued that the guardians could be breaking the law and suggested that the miners’ wives should apply on mass for admission into the workhouse.[46] Williams, Charlie and a group of miners’ wives decided to implement a plan that women should seek admission to the workhouse by obtaining the necessary orders from the relieving officer. Consequently, by 14 August the relieving officer in Cinderford had received over 100 applications for admission to the workhouse.[47]

On the 13th of August, the local press published the latest figures of men returning to work in the Forest pits. Apart from the safety men, the figures were: Eastern United 260, Lightmoor 272, Norchard 75, Waterloo 28, New Regulator 14, Slope 13, New Fancy 15, and Oldcroft Colliery 43 giving a total of 720 out of about 6,000. Most of these men were from East Dean, the district covered by the Westbury Board. Only a handful of men had returned to the pits in West Dean covered by the Monmouth Board who were still providing relief to the families of locked-out miners.

Protest

In addition to the plan that women should seek admission to the workhouse on 20 August, Williams and Charlie worked with a group of miners’ wives to organise a protest outside the Westbury workhouse and arranged transport from Cinderford. On Tuesday 17 August several hundred men, women and children met in Cinderford. Some were transported by coach but most had to walk the eight miles from the Cinderford area to Westbury.

The demonstration was held outside a meeting of the Board and was met by a large contingent of mounted and foot police. The demonstrators were rowdy but peaceful and were led by the women who sang songs including the Red Flag.

A motion presented by Booth and seconded by Mason that Purcell could be allowed to speak to the Board was refused by a majority vote of 13 to 10. An attempt by one of the members of the Board to present a motion to offer relief for one more week was ruled out of order by Rowlinson but the Board agreed to consider each of the 600 applications from the families of miners on merit. However, on 17 July 1926, 3,677 people were receiving Poor Law relief at the Westbury Union but by 14 August this number had been reduced to 388, which confirmed that the majority of families had had their relief cancelled.

A deputation of two men and two women asked for immediate relief for the hungry crowd and as a result, they were provided with bread and cheese by workhouse employees before returning home where they were greeted as heroines.[48] Meanwhile, the local women’s committee of the Labour Party raised a sum sufficient to pay 4s. per head to the miners affected by the Westbury Board’s decision.[49]

Occupation of Workhouse

On Friday 20 August the FDMA arranged transport from Cinderford to Westbury for about 300 women, children and babies, who had received orders from the relieving officer which entitled them admission into the workhouse. Some women brought as many as 6 or 7 children and, as there was no spare space on the coaches, some men and women set off on foot.

On arrival at the workhouse Williams and Charlie met Mr and Mrs Striven, the master and matron, and told them that they had no choice but to admit the women who possessed the necessary orders from the relieving officer. After receiving tea, bread and margarine some walked back to Cinderford while about 100 women and 200 children entered the institution. The accommodation was poor and crowded with only 100 beds, so most of the women stayed up all night and were later accused by the Strivens of shouting and singing all night, tearing pillowslips for the babies and refusing to make their beds or doing any domestic work. However, having made their protest, it was clear the institution could not cope, so they all decided to return to Cinderford the following evening.[50]

In 1987, Ellen Jones, at the age of 89 wrote an article in the Forest and Wye Valley Review, called When Charlie Mason led the Miners, describing her experiences of the occupation.

The miners’ leader was Charlie Mason of Brierley whose daughter is Winifred Foley, the author of A Child in the Forest. I don’t remember if he encouraged us or if we group of women and children of our own free will went to the Poor Law Institution at Westbury to try and get help for our men.

Some of us went very bravely – I with my two little girls and Jim, a baby in arms. While there we tried to make the best of it. One jolly woman would say. “Never mind girls – cheer up – I can smell bacon and eggs cooking for breakfast.” But no such luck! Just porridge!

The staff did their best for us down there but we couldn’t cope for long, so we all decided to return home. On the weary walk to Cinderford, we met our husbands coming down to bring us a bit of tea and sugar. The miners’ leader met me and asked if I would take my children into Cinderford Town Hall on the back way and when I did so I was met by a roomful of people cheering and clapping, I felt quite a heroine![51]

Report from the Master

On Tuesday 24 August, the Westbury Board of Guardians heard the following report from Mr Scrivens, the Master of the workhouse:

On Friday evening August 20th about 7-30 o’clock 86 women and 184 children were admitted to this Institution and on Saturday afternoon 7 women and 19 children were admitted, making a total of 93 women and 203 children. The applicants remained for 4 hours on the highway before coming in.

All of them had orders of admission from the Relieving Officer with the exception of one woman with five children who stated she had lost the order and 7 other women from Brierley who said they had been to the Relieving Officer that Friday evening but that he was out when they called. In the circumstances I admitted them.

The party were accompanied by Mr Mason (Guardian) and Mr Williams (Miners Agent). The usual Dietary for supper consisting of tea, bread and margarine, was served, but a considerable quantity was left on the plates, the women stating they could not eat margarine.

The young children, pregnant women and nursing mothers were given milk, and hot milk was supplied to babies three times during the night. Milk was served on admission when Mr. Mason was present and, he assisted in this.

Everyone had a bed with the exception of small children who slept two in a bed and plenty of bed clothing was provided. This was rather awkward to arrange at first as parties would not divide for some time and in some cases, they pushed the beds together, this accounts for the statements that 4 or 5 slept in a bed.

They kept singing and shouting up to midnight. The Matron appealed to them at midnight to be reasonable as they were upsetting the old people and those in the sick wards which was unreasonable by their singing and noise, they were not quiet all night.

The new blankets that had been purchased were trampled on. They burst the locks of cupboards open and tore the pillow slips to use for their babies and after use threw them down the lavatories. They refused to empty slops and upon being spoken to about this took up a threatening attitude towards the staff.

The women complained to Mr Mason on his arrival at Midday that they couldn’t obtain soap and water to wash their children with. This was not so as they were shown the bathroom where there were baths, bowls, hot and cold water and an unlimited supply of soap, towels and bath sheets. They were very noisy all night and none of the staff could go to bed until long past midnight.

Mr. Williams called on Saturday morning at 8 o’clock and asked if he could go through and speak to the women, but I told him I thought it was not advisable for me to allow him to do that, and he used rather insulting remarks towards me, one remark was that the meal supplied was pigwash. Not a single complaint was received about the dinner consisting of bread meat and potatoes and the children also received rice pudding. With regard to the bedding provided, all our spare beds were used and 20 straw mattresses were made up in the emergency – straw mattresses are used in many Institutions for this purpose.

There is ample accommodation in the Institution for the number we admitted and for more. It is within my knowledge that some of the women handed two shillings and half crowns to the Officials to buy biscuits for them and quite a lot of money was spent in this way in the village.

I should on behalf of the Matron and myself like to commend to the Board the untiring efforts of all the Indoor Officials, all of whom remained up all night as it was impossible to retire to bed on account of the noise and the fact that although we had settled them down comfortably for the night they would not do so.

I should also like to say that a number of the women on taking their discharge on Saturday afternoon expressed their appreciation of what had been done on their behalf and said they couldn’t possibly expect anything better in the circumstances.

Mr Mason came to the House on Friday the 20th of August and was shown by the Matron the accommodation in the women’s Block and the children’s Block which had been prepared for them, he expressed his approval of the arrangements and signed the Visiting Committee Book, he also inspected the Dietary Sheet.

On Saturday Mr Mason came to the House and was given an opportunity of inspecting the quarters and the condition they had been left by the persons admitted on Friday, but he declined.

Mr. Mason addressed the Women in the House and said he would see what could be done about the Dietary on Tuesday if they would remain in the House. In the presence of the women, he was told that the Dietary could not be altered.

B.H.Scriven (Master).

The Board passed a motion commending the Master and indoor staff on how they had discharged their duties. This was followed by a motion presented by Booth and seconded by Brain that the Board continue to provide outdoor relief but this failed. However, the Board did agree to hear a statement from a deputation representing the families of locked-out miners, but their appeals to continue to provide relief were ignored.

Consequently, the Labour members became very angry with the attitude of the majority of Board members who were unprepared to listen to the arguments presented by the delegation. Arguments broke out and, in the end, the meeting had to be abandoned.[52]

Destitution

With the support of Williams and Charlie, the miners’ wives continued their campaign and organised two marches headed by brass bands, one from Cinderford and the other from Drybrook, which converged at the Co-operative Society’s field in Cinderford. In his speech, Williams argued that the Westbury Board’s decision might be illegal if it led to destitution.

The Ministry of Health warned the Westbury Board that it was their statutory duty to provide relief to anyone in their community who was destitute. However, in the end, no action was taken against the Board because it argued that its duty to prevent destitution was covered by law if the workhouse was offered as an alternative.

Some Forest mining families were running out of food and this had a significant impact on the decision of some men in the Forest of Dean to return to work. This situation contrasted with other areas where the miners and their families continued to receive relief. For John Williams:

This was the beginning of the end of the strike in the Forest of Dean. Nearly every day now I was called to most of the collieries to deal with men returning to work. The workmen had been out of work for over four months. They had not received a penny strike pay from our funds. We had no funds. The only payment received by the workmen of this district was one payment out of what was described as ‘Russian Money’.[53]

Evacuation

Consequently, it was decided to organise an evacuation scheme for children to stay with sympathetic families who could afford to look after them. It was agreed that for families with more than three or more children, the fourth child should be evacuated to London. One of those chosen was Winifred Foley, the daughter of Charlie. Winifred recollects her expereince on arriving in London:

One by one the children were led out as people decided which of them to take into their homes. As the numbers thinned we huddled in the middle. Soon only two were left: Florence and me. ‘O God, don’t let me be last!’ I prayed. After a pause, Florence was taken out. But it seemed that the stomach of charity was not strong enough to take me. I hung my head in shame. I was not only unwanted, I was a nuisance. To make it worse I couldn’t hold back my tears. I wiped them away quickly with the sleeve of my cardigan. As I stood there alone, a thin young man with a very kind face and manner hurried up to me. ‘Come on, kiddie,’ he said, ‘I know where we’ve got a nice home for you. Are you hungry?’[54]

Defeat

Charlie continued to press the Board to support the destitute in his community. At a Board meeting on 7 September 1926, he protested over a decision to refuse relief to a widow who was the mother of a locked-out miner. However, Rowlinson argued that the case was the same as all the others in that work was available to the son and it was his duty to maintain his mother.[55]

Meanwhile, pressure on the families in West Dean increased when, on 9 October, the Monmouth Guardians announced they would cut off all relief to the dependents of locked-out miners. The Labour members on the Board protested but to no avail. At about the same time, a similar decision was made by the Guardians on the Ross and Chepstow Boards.

However the drift back to work was now beginning in other districts and by the end of November, the MFGB Executive had no choice but to accept defeat and contacted the government and informed them they would accept a reduction in wages provided they were framed by a new national agreement. After consulting with the owners, the government came up with new proposals for a return to work but insisted on district agreements on wages and hours. On Friday 18 November, the Gloucester Citizen announced:

Mr David Organ, President of the Dean Forest Miners’ Association, presided on Wednesday night over a meeting of the Executive Council, when the business was to receive reports brought in from the lodges to the view of the rank and file on the Government memorandum. The result was somewhat of a surprise, for the report presented at the close of the examination of the returns showed that there was practically unanimous expression of acceptance of the Government terms. Mr Jack Williams, the Miners’ Agent, therefore received a mandate to say that the voice of the Forest of Dean miners was favourable to a settlement. The advice was given that men who had not already done so should sign on at once. The dispute in the Forest of Dean coalfield is therefore at an end.[56]

Charlie and his colleagues fought hard and did the best they could against the combined forces of the colliery owners, the government and their supporters within the established elites in the Forest of Dean. The seven-month national mining lockout of 1926 was one of the most important industrial disputes of the twentieth century. It came to symbolise the defeat of the labour movement in the interwar years, casting a long shadow over industrial relations in the mining industry, and epitomizing the predicament of British miners in the early decades of the century.

Blacklisted

Most of the experienced FDMA members were blacklisted. Gilbert Roberts remembers Charlie was also blacklisted:

After the strike was over, he wasn’t allowed back to his pit. It was seven years before he worked in a pit again, this time at Northern United.[57]

Winfred Foley, remembers the support her family got from other members of the community and during her dad’s “seven-year victimisation from the pits these men did not forget us”.[58] She added:

The injustice of this made Dad into a Socialist, his outspoken condemnation of local pit-owners leading to victimisation and barring him from work in the Forest mines for seven years, which made our lot worse than most. With a couple of other erudite miners, he found an outlet for his thoughts and feelings in discussions and arguments round the fireside.[59]

Three of Charlie’s close friends were the brothers Tim, Micah and Albert Brain. Tim and Albert worked at Cannop as deputies and Micah worked at Waterloo as a colliery watchman. A deputy is a colliery official charged with the supervision of safety, the ventilation of the workings, the inspection of timber work, etc. Deputies carried on working through the lockout with agreement of the FDMA to keep the pits safe, free from flooding, etc.

When Marion, who was Albert’s daughter, asked Mrs Hale, her teacher at Slad School in the 1920s what made Charlie different? Mrs Hale said, Charlie was a communist. He was about what Communism really means – fair shares for everyone – and added that was why he couldn’t get a job and why they were so poor.[59b]

The 1930s were tough but even more so for those miners, like Charlie, who were blacklisted. He obtained some work where he could but it was hardly enough for his family to live on. Consequently, Bess and Winifred had to leave home and get work as servants working for the wealthy and send money home. Winifred said Charlie was a skilled craftsman and engineer and kept busy at:

His little wooden workshop hut where he mended our boots, patched up pit-lamps, and put broken worn-out furniture together again for us and his neighbours, all for goodwill and because he had the skill to do it. [60]

He repaired an old lathe someone gave him and taught himself how to use it so well that he became the honorary village carpenter and bodger (traditional woodturner), producing turned chair legs and other wooden objects. With a large old metal container and a pipe bellows, he made a miniature smithy to mend pit-lamps and tools, and do other small metal repairs. He was a keen herbalist and a bee-keeper, so we always had honey. He built a little glass hive in the living-room window for us children to observe what went on in a beehive.[61]

Winifred says her Dad loved nature and was a keen herbalist and used his homemade medicines to cure:

us with his home-made potions. He gathered elderflower, yarrow, camomile, and other wild herbs, dried them and stored them in brown paper bags for his bitter brews. Constipation, coughs, colic, sickness, diarrhoea, sores, fever, delirium — whatever we had, out came the dreaded brown jug, and onto the hob it went with its infusion of herbs.[62]

Charlie also enjoyed developing and printing photographs and making wireless sets:

Wireless was in its infancy, especially where we lived, and Dad was fascinated by the phenomenon of sound waves. He bought a book about it and reckoned if he could afford the parts he could build a set.[63]

Northern United

However, things improved with the opening of a new deep pit, Northern United, by Henry Crawshay and Company in 1934. The manager, Joseph Morrison, constructed a house for himself nearby and hired Charlie to build the garden. The pit was situated near Brierley and, as Morrison was seeking skilled miners, Charlie obtained a job there as a maintenance man. Within a few years, he was promoted to the role of colliery deputy (examiner) whose job was to examine a designated area of the mine before a shift started to ensure that all the statutory rules were complied with and the area was safe for the men to work in.

Mining is by its very nature dangerous and accidents often happen. On 25 May 1936, John Roberts (age 50) was killed by the falling of 3 cwt of dirt from the roof of the face. His death was due to internal haemorrhage and fracturing of nearly all his ribs. During the inquest, it was reported that:

Charlie Enoch Mason, colliery examiner, of Brierley, said he went to fetch the stretcher, but found that it had been removed from its usual place at the bottom of the pit. He phoned to the pit head for it, and it was brought quickly, without any delay. Mr. Morrison explained that the stretcher had been taken up to be cleaned. [64]

About this time, Charlie started to suffer from deafness and so he was downgraded from his role as examiner and was sent back to work as an miner. He remained a member of the FDMA and continued to attend their meetings and took on responsible roles.

World War Two

Charlie, just like his colleagues at Northern, was committed to supporting the government in its war against fascism. As a result, the Forest miners worked flat out during the war including working extra shifts and initially working through all their holidays. Charlie was a member of the production committee at Northern whose task was to consider all possible ways to increase productivity, reduce absenteeism and avoid unnecessary industrial disputes.

The government and media applied a huge amount of pressure on the miners to increase productivity because of the shortage of coal for the munitions industry. However, the labour force was getting older and some miners were disabled and suffering from lung disease and unable to work the long hours expected of them resulting in sickness and absenteeism. An additional problem impacting productivity was a huge shortage of skilled labour as many miners had volunteered for the military or moved to better paid work with safer and healthier conditions. As a result in the Spring of 1941, the government introduced an Essential Work Order (EWO) which placed a statutory requirement on all skilled workers to register and tied workers to jobs considered essential for the war effort such as munitions, agriculture and mining.

The EWO empowered the Ministry of Labour to prevent workers from leaving the industry without permission and to direct skilled workers to wherever they were most needed. The EWO made persistent absentees the subject of the discipline of the national service officer. Charlie now had no choice but to remain working long hours with few breaks. However, he was part of an ageing workforce often suffering from lung disease and a shortage of food. Exhaustion soon crept in and so in the summer of 1941, after a strike at Princess Royal colliery, the Forest miners voted to take their one week’s holiday which was their right.

Death

The constant pressure to increase production coupled with exhaustion and long hours inevitably impacted safety. Charlie was now in his late fifties and was still required to carry out heavy physical work. Fifteen men were killed while working in Forest pits during World War Two.[65]

After the war in Europe ended in September 1945, there was still a shortage of coal and pressure on the miners to raise productivity and the EWO remained in place. On 13 December 1945, Charlie Mason became one more person among the thousands killed in the coalfields of Britain.

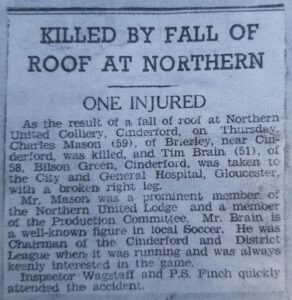

The Dean Forest Mercury on 21 December 1945 reported:

A well-known and highly esteemed Brierley inhabitant, Mr Charlie E. Mason (59) was accidentally killed at Northern United Colliery, on Thursday, Dec 13th, as reported in last week’s Mercury. He was a member of the Northern United Lodge and the Production Committee and a prominent Trade Unionist, and highly regarded by the officials and his fellow workmen. He was keenly interested in the social life of the district. He leaves a wife, one son and four daughters to whom the greatest sympathy is extended.

Charlie was working with his long-term friend Tim Brain. The accident happened while they were using a ‘Sylvester’ to pull a ring from a roadway using a timber setting, which was used to support the roof, as an anchor.[66] Tragically instead of pulling the ring, the timber setting moved and this caused the roof to collapse crushing both men.

The alarm was sounded. Within a short time rescuers were attacking the mound of debris which had engulfed the two friends. Brain, severely crushed and suffering with a broken leg, was quickly located. ” Never mind me—find Charlie,” he pleaded as he pointed out the spot in which he last saw his comrade alive. And still trapped, he watched the rescue party turn to dig for Mason and later he saw them extricate him. But Mason had worked his last shift —he was dead.[67]

On Saturday 15 December a meeting of the Forest of Dean Trades Council, which is made up of delegates from nearly all the trade union branches in the Forest, passed a resolution moved by the secretary, G D H Jenkins, to send a letter of sympathy to Charlie’s family.

Jenkins paid a warm tribute to the work Mr Mason had done for the betterment of the working man.[68]

The chair, William Ellway, added that:

Mr Mason was sincere in his convictions and full of enthusiasm for the cause of workers. He is another of our comrades who had died with his boots on. That is often said of soldiers: it can be said of miners.[69]

The day of Charlie’s funeral was 17 Dec 1945. It was a cold, windy day with sleet and snow. Despite Charlie’s agnosticism, a preacher led a small service outside his cottage in Brierley which was attended by a large crowd of mourners. Charlie’s work comrades then carried his coffin through the woods to the Holy Trinity Church in Drybrook where the internment took place.

They carried him in relays, nearly two miles to the church, and everyone was glad to take the burden.[70]

A huge crowd attended his funeral including many relatives, friends, and work colleagues. Representing the FDMA were William Ellway, chairman, John Williams, agent, Harry Morgan, finance officer, Wallace Jones, safety officer and Harry Barton, the Forest of Dean representative on the South Wales Miners’ Federation Executive. Among the flowers there was a “Tribute from “A Friend.”

In him we have lost a great champion in the cause of humanity. All who knew him remember his struggles for a better system of society, his work with the council: his connection with the Miners’ Executive, and pit Production Committees earned him great respect. Some will remember his leading a band of women to Westbury Institution in order to strengthen the case of the miners on strike, He was an inspiration to the young; he comforted the old with a reasoning which they understood was unselfish to a fine degree. [71]

On 4 January the Dean Forest Mercury published the following letter:

You have been very generous to the space allotted on the death of my dear father, Charles Mason. But from a heart broken in grief at his passing, I feel the public should know how just and kind and a dear parent he was. And in his memory, I would urge fathers to practice tolerance, love and understanding towards their children. Thank you, Dad from one of his children.

John Williams paid tribute to Charlie as follows:

Charlie was held in respect, a reflection of his own estimable life. He was not without his faults, but the few he had were eclipsed by his many virtues and outstanding merits. The highest testimony to his integrity is that his innumerable friends thought, felt and said the same about him when he was alive as they are thinking, feeling and saying now. Charlie Mason had known and experienced prolonged and intense poverty, and during his life had endured severe privations and hardships because of his convictions, yet he bore no malice towards those who brought these privations and hardships upon him. Charlie Mason was a thinker and it was always a delight to listen to him. He was sometimes away from the point at issue, but by some means or other, he was more charming and graceful on those occasions than when he addressed himself to the point. The world would be better in many ways if there were more people like Charlie Mason.[72]

The inquest was conducted by the Forest of Dean Divisional Coroner, (M. F. Carter). The local Inspector of Mines, W. E. Thomas, who was present at the inquest, strongly condemned the anchoring of the Sylvester to a wooden prop. However, Lewis Witt, the undermanager at Northern United Colliery argued that considering the peculiar circumstances involved – the nature of the soft roof – there was some justification for the method the two men had used.

Clearly, there was pressure to get the job done quickly. Normally it was customary for the men to take the rest of the shift off out of respect. However, at this time, the demand for coal was so great there was no time for respect and the men were told to carry on working for the rest of the day.

Ralph Anstis said that whenever his name was mentioned in the Forest a smile came over people’s faces. ‘Oh, yes, I remember Charlie Mason’ they would say with affection’. [73]

[1] Ralph Anstis on Forest of Dean Community Radio 2002-2003 sent to me by Clive Mason and Paul Mason.

[2] Winifred Foley, A Child in the Forest (London: BBC, 1974), Winifred Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, (London: Abacus, 2009) and Winifred Foley, No Pipe Dreams for Father (Coleford: Douglas Mclean, 1977).

[3] Winifred Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie (Oxford: Isis, 2002) and Winifred Foley, In and Out of the Forest (London: Century Publishing, 2009)

[4] In and Out of the Forest, 44-45.

[5] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 66-67.

[6] Foley, In and Out of the Forest,

[7] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 5.

[8] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 14.

[9] Foley, In and Out of the Forest, 143.

[10] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 95.

[11]

Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 17.

[12] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 12.

[13] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 15.

[14] Ian Wright, God’s Beautiful Sunshine, The 1921 Lockout in the Forest of Dean (Bristol: BRHG, 2020).

[15] Dean Forest Mercury 8 April 1921.

[16] Anstis, Blood on Coal, 106.

[17] Dean Forest Mercury 15 July 1921.

[18] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 68-69.

[19] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 83.

[20] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 103.

[21] Gloucester Citizen 17 March 1922.

[22] Gloucester Citizen 13 December 1923.

[23] Ian Wright, Coal on One Hand, Men on the Other, The Forest of Dean Miners’ Association and the First World War 1910-1922 (Bristol: BRHG, Chapter Four.

[24] Western Mail 7 March 1923.

[25] Gloucestershire Echo 12 November 1924 and Westbury Board Minutes 11 November 1924..

[26] During the 1898 miners’ strike in South Wales the Merthyr Board of Guardians decided to support destitute strikers, even though they had voluntarily withdrawn their labour. As a result, coal companies took the Merthyr Board of Guardians to court because they did not want striking workers to gain any financial support. In the subsequent famous High Court ruling in 1900, the Master of the Rolls (the equivalent of today’s Supreme Court), ruled the policy of relieving the strikers had been unlawful. Consequently, the Guardians were now only allowed to help dependents of strikers if they were destitute while single men had no access to poor relief whatsoever. The high court verdict became known as The Merthyr Tydfil Judgment of 1900.

[27] In the Forest of Dean, there was a higher proportion of owner-occupiers than in most other mining areas. This was because, after the 1831 riots, squatters who had encroached on statutory Forest land were allowed to remain in their properties and many were given freehold status.

[28] The recommended figures by the Ministry of Health were: 12s for a miner’s wife and 4s for a child (up to age 14) in the form of a loan up to a maximum of 32s per week.

[29] Westbury Board Minutes 18 May 1926.

[30] Dean Forest Mercury 14 May 1926.

[31] Dean Forest Mercury 14 May 1926 and Gloucester Citizen 19 May 1926.

[32] Dean Forest Mercury 14 May 1926.

[33] Dean Forest Mercury 4 June 1926 and Gloucestershire Chronicle 4 June 1926.

[34] Gloucestershire Chronicle 21 May 1926, Gloucestershire Chronicle 4 June 1926 and Westbury Board Minutes 1 June 1926.

[35] Dean Forest Mercury 11 June 1926.

[36] Dean Forest Mercury 11 June 1926.

[37] Dean Forest Mercury 11 June 1926.

[38] An excellent history of the Co-operative Society in the Forest of Dean can be found in Alistair Graham’s book The Forest Pioneers, The Story of the Co-operative Movement in the Forest of Dean published by the Co-operative Society in 2002.

[39] Dean Forest Mercury 18 June 1926.

[40] Dean Forest Mercury 18 June 1926.

[41] Westbury Board Minutes 22 June 1926.

[42] Westbury Board Minutes 3 August 1926.

[43] Gloucester Citizen 4 August 1926.

[44] Gloucester Journal 7 August 1926.

[45] Daily Herald 19 August 1926.

[46] Gloucester Citizen 12 August 1926.

[47] Gloucester Journal 21 August 1926.

[48] Gloucester Journal 21 August 1926.

[49] Daily Herald 19 August 1926.

[50] Gloucester Citizen 21 August 1926 and 25 August 1926.

[51] Forest of Dean Review, 1987. Thanks to Paul Mason for sending me this article

[52] Westbury Board Minutes 24 August 1926.

[53] John Williams, A Statement, 23 November 1961.

[54] Foley, A Child in the Forest, 104.

[55] Gloucester Citizen 15 September 1926.

[56] Gloucester Citizen 18 November 1926.

[57] Phelps, Forest Voices, 68.

[58] Foley, No Pipe Dreams for Father, 36.

[59] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 2.

[59b] Oral history of Marion and David Williams held at the Dean Heritage Centre. Thanks to Nicola Wynn.

[60] Foley, In and Out of the Forest, 75.

[61] Foley, Great Aunt Lizzie, 1-2.

[62] Foley, Full Hearts and Empty Bellies, 91-92.

[63] Foley, In and Out of the Forest, 107.

[64] Gloucester Journal 30 May 1936.

[65] Dave Tuffley, Roll of Honour, Forest of Dean Local History Society.

[66] Sylvester is a coal mining jacking device which comprises a ratchet bar with a handle (and attaching block), chain and hook.

[67] Gloucester Citizen 25 January 1946.

[68] Dean Forest Mercury 21 December 1945.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Foley, No Pipe Dreams for Father, 35.

[71] Dean Forest Mercury 21 December 1945.

[72] Maurice Bent, The Last Deep Mine of Dean (Forest of Dean: Self-Published, 1988) 128-129

[73] Ralph Anstis on Forest of Dean Community Radio 2002-2003 sent to me by Clive Mason and Paul Mason.

Wallace Jones was born in Cinderford in March 1894, the son of a grocer, Edwin Jones. He had 8 siblings two of whom died at a young age. Wallace left school in 1909, aged thirteen, to become an apprentice baker. The 1911 census lists Wallace working as a woodman on the Crown Estate. Soon after he moved to Aberdare to work in one of the Powell Duffryn collieries.

Wallace Jones was born in Cinderford in March 1894, the son of a grocer, Edwin Jones. He had 8 siblings two of whom died at a young age. Wallace left school in 1909, aged thirteen, to become an apprentice baker. The 1911 census lists Wallace working as a woodman on the Crown Estate. Soon after he moved to Aberdare to work in one of the Powell Duffryn collieries.