Reginald Godfrey Crockett was born in Abenhall near Mitcheldean in the Forest of Dean in 1896. He was the eldest son of Ernest and Elizabeth Crockett and had eleven younger sisters and two younger brothers. His father worked as a general labourer in local quarries and at Mitcheldean cement works. This essay provides an outline of his criminal career including details of events in his early history that may have impacted on his relationship with authority and the life choices he made.

Reginald Crockett started getting into trouble with the authorities at a young age. In July 1908, he was up before Littledean magistrates for the theft, committed jointly with a friend, of 2 shillings(s) worth of peas from a farmer’s field. He was bound over to the sum of £5 plus 10s costs.[1] In October 1908, he was bound over by Littledean magistrates and fined 8s costs for letting off fireworks on a public highway.[2] These sums were equivalent to about two days of wages and probably had to be paid for by his father. On 25 August 1911, Crockett appeared before Littledean magistrates accused of entering “enclosed premises” and was bound over.

In 1911, Reginald Crockett was working as a labourer at Mitcheldean cement works where his father also worked and by 1912, at the age of 17, he was living in lodgings. In November 1912, he was charged with stealing a watch that had been left attached to a motorbike in Mitcheldean. He pleaded guilty at Littledean magistrate’s court and was sentenced to one month in prison as “his record was a bad one”.[3]

World War One

In 1914, Crockett was living in Tredegar and working at Graham’s Navigation Colliery. On 26 October 1914, he joined the 5th (Reserve) Battalion Manchester Regiment and then transferred to the 3rd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment. He was posted to France on 13 February 1915 where the 3rd Battalion of Monmouthshire suffered heavy casualties at the Second Battle of Ypres when British troops were subjected to German chlorine-gas attacks. Private W. Hay of the Royal Scots arrived in Ypres just after the chlorine-gas attack on 22 April 1915 and described what he saw:

“We knew there was something was wrong. We started to march towards Ypres but we couldn’t get past on the road with refugees coming down the road. We went along the railway line to Ypres and there were people, civilians and soldiers, lying along the roadside in a terrible state. We heard them say it was gas. We didn’t know what the hell gas was. When we got to Ypres, we found a lot of Canadians lying there dead from gas the day before, poor devils, and it was quite a horrible sight for us young men. I was only twenty so it was quite traumatic and I’ve never forgotten nor ever will forget it.”[4]

Lance Sergeant Elmer Cotton described the effects of chlorine gas:

“It produces a flooding of the lungs – it is an equivalent death to drowning only on dry land. The effects are these – a splitting headache and terrific thirst (to drink water is instant death), a knife edge of pain in the lungs and the coughing up of a greenish froth off the stomach and the lungs, ending finally in insensibility and death. The colour of the skin from white turns a greenish black and yellow, the tongue protrudes and the eyes assume a glassy stare. It is a fiendish death to die.” [5]

On 8th May 1915 during the 2nd Battle of Ypres, the 3rd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment made one of the most gallant stands in military history when in obeying the order to stand to the last man, the battalion was practically annihilated, without giving an inch of ground to the enemy, the battalion lost 703 in killed and wounded; all but a handful of officers and men remained. The survivors were merged with those of the 2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment which had suffered a similar fate.[6] Around this time Crockett was shot in the head and was returned to Britain wounded on 12 May 1915.

On 3 September 1915, Crockett was brought before a court-martial in Abergavenny and sentenced to 42 days in a military prison for theft and a miscellaneous range of other offences.[7] On 12 October 1915, in Abergavenny, Crockett married 26-year-old Winifred Finch originally from Dudley who had moved with her family to Gloucester where her father worked as a foundry manager.[8]

At some same stage over the winter, Crockett deserted and went on the run. He later claimed that he was encouraged to desert by his wife. However, by April he had been captured and on 17 April 1916, Crockett was court-martialled at Oswestry. He was found guilty on three accounts of going absent without leave and two accounts of theft and sentenced to 12 weeks in a military prison.[9] Military prison discipline at this time was particularly harsh.

He was discharged from the army on 1 February 1917 either because of his health or because the army felt he was unfit to be a soldier. Crockett is listed as receiving the 1914 – 1915 Star Medal, British War Medal and the Victory Medal.[10]

Horse Theft

Crockett returned to the Forest of Dean and began a career as a horse thief. Stealing horses had a long history in Gloucestershire mainly because it was an attractive crime for the destitute rural poor and enabled them to make a quick profit for little effort. Horses were left out in fields overnight and could easily be taken and sold for a good price at nearby markets. In 1915 a horse could be sold for about £50 which is equivalent to about £6000 in today’s money. It was a very risky undertaking as it involved heavy penalties. However, it was probably far more widespread than the conviction figures suggest as most offenders were probably not caught.

In the years 1735-1799, the Gloucester Assizes passed 615 death sentences which led to 121 hangings, including 21 for horse theft and 13 for sheep theft. At this time horses were usually owned by the local gentry and it was they who sat at the Assizes as judge and jury. They were determined to prevent the loss of their property and believed hanging would be an effective deterrent.

Not all cases of animal theft during this period resulted in execution and by the 1830s, in most cases, the death sentences were commuted to transportation for life. However, in some cases executions for animal theft continued with 12 hangings for horse theft, 6 for sheep theft and one for cattle theft in Gloucester between 1800 and 1826. The last hanging in Britain for sheep theft was in 1831 and for horse theft in 1829.[11]

After 1832, those convicted of animal theft were usually transported. There were 1,680 men and women transported from Gloucestershire (including Bristol) to Australia between the years 1783-1842, many of these for animal theft.[12] There were about 60 men and women transported from the Forest of Dean area between 1783-1842 and about one-third of these were for animal theft.[13] Transportation continued up to the 1860s, after which offenders were subjected to a punishment of hard labour in a prison.

Harnesses

In July 1917, Crockett was arrested for the theft of some harnesses from several local premises in the Forest of Dean. He was identified after being spotted on one of the premises and also for taking a harness to be altered at a local shop. Harnesses were essential items for horse theft and it was likely he planned to use them for this purpose.

Crockett was easily identifiable as he was 5ft 7in high with war wounds which left a large scar on the side of his neck and the top part of one finger missing. He appeared before the Littledean magistrate, Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel Kerr, and pleaded that he had spent two years in the trenches and had been wounded and gassed four times and as a result didn’t even know what he was doing sometimes.[14] He said he knew he was entitled to no mercy but asked to be fined rather than sent to prison. Kerr, who owned a number of horses and enjoyed hunting, sentenced him to two months in prison.[15]

On his release, Crockett spent the next few years in South Wales around Ebbw Vale and was involved in more petty crime appearing before the courts on three separate occasions, resulting in three separate spells in prison of six months. In one case, on 12 September 1918, he was sentenced to six months in prison for stealing a harness implying he was still planning to steal horses.

Homeless

On Crockett’s release from prison, Winifred refused to have anything to do with him. On 26 February 1919, he approached her in the street near her house on Landsdown Road in Gloucester resulting in an alternation. Winifred accused Crockett of grabbing her by the arm. On the other hand, he accused her of attacking him with a hatpin and poker when he returned later to collect his belongings. Gloucestershire Echo 22 March 1919 reported that they both issued summons against each other for assault but withdrew them during the hearing before a magistrate when it was revealed that they had agreed to get a divorce.

At the hearing, Crockett gave his address as High Street, Mitcheldean but it can be assumed his family also did not want to help him because he was now homeless, A week later was arrested for horse theft.[16] On 9 April 1919, he was brought before the Gloucester Quarter Sessions where he was charged with stealing a horse valued at £55 from a field in Longlevens near Gloucester on 25 March. Witnesses confirmed he travelled with the horse by train to Newport where he sold it for £47. Crockett was found guilty and, after admitting to another charge of horse theft on 6 March, was sentenced to twelve months with hard labour in Gloucester prison.[17]

Crockett was released on 2 February 1920 and told the authorities that he planned to live in Gloucester and work as a labourer. However, in March 1920, he was arrested again for theft of a horse valued at £89 and was committed for trial before the Herefordshire Quarter Sessions.[18] The actual theft could not be proved and so, on 5 April 1920, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison after pleading guilty to receiving a stolen horse.[19] The Dean Forest Mercury reported:

“Reginald Godfrey Crockett, a Forest of Dean and Gloucester man, before he was sentenced to fifteen months imprisonment with hard labour at Hereford Quarter Sessions on Monday, said he had been twice wounded in the war and had been gas poisoned and suffered from shell shock. He pleaded guilty to the second of two charges – receiving a horse knowing it was stolen. He sold it to a Gloucester farmer for £50 and represented he had bought it from Dick Smith a Ruardean gipsy. The gipsy could not however be traced. The horse disappeared from Holmer, near Hereford and after the Gloucester farmer sold it to a Rodd farmer for £62 at Gloucester market it was reclaimed and the later lost his money. A detective said the prisoner who wore the 1914-1915 ribbon had spent some of his army life in prison and when convicted at Gloucester, 13 months or more ago, for horse stealing, and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment he admitted to having been convicted at Ebbw Vale and sentenced to three terms of six months each.”[20]

However, it was not long after being released from prison he was again being sought by police for horse theft. This from the Police Gazette:

London

In 1922, Crockett was living in London and in trouble with the law. On 26 April 1922, he was up before the Central Criminal Court in London accused of stealing 120 bags of onions worth £130, using a forged delivery order. He was sent to Wandsworth prison for nine months of hard labour after two cases of stealing horses were taken into consideration. On his release on 11 December 1922, he claimed he was planning to return to Mitcheldean to work as a greengrocer.

However, in 1923 he was living in St Pancreas in London. On 23 September 1924, at the Central Criminal Court, he was sentenced to eighteen months in Wandsworth prison for obtaining wireless accessories, 100 headphones and credit by fraud. He was released on 24 December 1925 and told the authorities he planned to work as a painter in Euston.[21]

In July 1926, he was arrested under the alias Reginald Charles Turner with two accomplices and charged at the Winslow Petty Sessions with several burglaries in the Buckinghamshire area. He was arrested after the car was seen driving fast and crashing into a lamp post outside the Royal Buckingham Hospital. The car was subsequently stopped at a police roadblock. Crockett’s records state that:

“With confederates, one of whom was a woman, he drove in a motor car to various provincial towns and called at garages where he made a small purchase and at the same time observed where the petrol and oil stores were situated then, later, called and broke into the garages and stole petrol and oil, etc. In some cases, left the car in a field some distance from the scene of the crime. He often approached the premises from the rear, and in one case cut through bolts, holding swing doors, with a hack saw whilst in others forced doors with a screwdriver.”[22]

The gang were also accused of breaking into a counting house and stealing a number of tins of petrol, postage stamps and other articles. Crockett was now aged 30 and his accomplices were Edith Mann, aged 25, who said she had lived with Crockett for some time and Walter Jack Watson, aged 27. The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press 16 October 1926 described the trial at the Buckingham Quarter Sessions:

“The jury returned verdicts of guilty on each count against all the prisoners and recommended leniency for the girl. No evidence was called in respect of the charge of entering a garage at Watford. Turner admitted a conviction at Hereford under the name of Crockett. Supt. Callaway said that Turner’s real name was Reginald George Crockett. He read out a list of previous convictions against him dating from 1908. He was a married man living apart from his wife. He had been co-habiting with Mann. They had no fixed address and left their last address on the date of the Winslow offence. He was the cause of the girl’s downfall. She had never been previously convicted, neither had Watson, who had lived a respectable life until he became acquainted with Crockett. The Chairman remarked that Crockett was the one who appeared to have led the others astray. Crockett was sentenced to three years penal servitude in Dartmoor prison. Watson and Mann were bound over for 12 months.” [23]

Crockett was released on licence on 16 January 1929 and moved to Gloucester where he planned to get a job as a driver. He was back in the Forest by March 1929, when he was charged with stealing a cycle and Exide battery in Cinderford.[24] He was arrested and brought before Gloucester Quarter Sessions in early April and found not guilty and released. However, he was now homeless and set out towards Oxfordshire sleeping rough, living a life on the roads as a tramp and surviving by theft. He no longer was able to keep up with the supervision order as directed by the courts. It wasn’t long before he was arrested and charged with a series of offences linked to sheep thefts in the area.

Sheep Theft

Sheep were commonly kept by farmers in Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire and were easy targets for thieves. However, each owner marked his sheep with an easily identifiable signature and so they were difficult to sell and easy to trace. In June 1929, Crockett was arrested for stealing 42 sheep while tramping in Oxfordshire. He stole the sheep and lambs from four separate fields owned by different farmers near Deddington and then drove the sheep to Banbury and sold them under an assumed name. He was arrested before he could cash in the cheque.[25] He appeared before the Oxford Quarter sessions on 2 July 1929 charged with stealing 42 sheep. He was sentenced to three years in prison and four months for failing to report to the police under the supervising order from his previous conviction.[26]

In addition, on 1 August 1929, Crocket was committed to appear before Gloucester Quarter Sessions for stealing 22 sheep from a farmer in Forthampton and sold them at Upton-on- Severn market.[27] The sheep were easily identifiable by their markings and Crockett was identified as the man who sold the sheep. The Tewkesbury Register reported the case:

“Inspector R. J. Hedges said the prisoner was a native of Mitcheldean and had led a life of crime. Whilst in the army he was three times convicted of theft, and since had been convicted in 1918 (six months), 1919 (12 months), 1920 (15 months), 1922 (9 months), 1924 (18 months), 1926 (three years’ penal servitude and 6 months’ imprisonment). It was explained that the last sentence was passed at Oxford Sessions when various cases were taken into consideration. For certain reasons that case was not included. The Recorder said that prisoner wrote an excellent letter and produced a statement by him. The handwriting was excellent, and it contained at least one Latin quotation which was perfectly correct. Instead of taking advantage of his education, he had apparently drifted into a life of crime. He would be sentenced to three years’ penal servitude to run concurrently with the present sentence, which meant his punishment would not be increased. An order for the restitution of the sheep was made.”[28]

Subsequently, Crockett was transferred from Gloucester prison to Dartmoor prison. Crockett was released on 6 June 1932 and told the authorities he planned to live in Gloucester and work as a stud groom. However, he ended up living in Shepherds Bush in London and was unemployed for some time until he obtained the role of a detective at a film studio at Shepherds Bush. He was sacked after a week because his services were not deemed satisfactory. He then set himself up as a general dealer in Shepherds Bush where he appeared to live with a variety of women listed on the electoral register as living at Crockett’s various addresses in Shepherds Bush and Hammersmith: Nancy Crockett in 1934, Annie Crockett in 1935 and 1936, Nancy Crockett in 1937, Alice Crockett in 1938 and Edith Crockett in 1939.

Shepherds Bush

In October 1934, Crockett was arrested and charged with sheep theft with his brother Clarence as an accomplice. He was brought before the magistrates at Northleach where it was alleged that on 27-28 July, he stole six lambs from the Stowell Park Estate in Yarworth near Cheltenham. A description of the lambs was circulated and in August they were found in the possession of Clarence Crockett who lived in Mitcheldean and was an animal dealer. Clarence claimed he had bought them from his brother. Witnesses provided a statement that they saw the two men together with lambs in Mitcheldean. The police went to Shepherds Bush and examined Crockett’s van and found sheep manure and wool inside. Reginald Crockett was committed for trial at Gloucester Quarter Sessions and the case against Clarence was dismissed.[29] At his trial, Crockett claimed he had bought the lambs from a man named Young but the Jury did not believe him and the judge said:

“You have a very long list of convictions. There are three sentences of penal servitude, and the last two are for sheep stealing. Three years of penal servitude does not seem to stop you, and the decision of the court is that you will receive four years of penal servitude.” [30]

However, he was released by early 1936 and moved back to London where he was now part of a network of criminals stealing and fencing stolen goods. In March 1936 he was up before Uxbridge Police Court with two other men for breaking in and stealing a large number of shoes and hosiery from Freeman, Hardy and Willis in Kingsbury near London valued at £117 on 24 February. They were also charged with breaking and entering and stealing shoes and other items to the value of £186 from the True Form shop in Eastcote near London on 11 March. Crockett and two associates, all hardened criminals with a long history of convictions, were known to the police who searched their flats and discovered the stolen goods. The three men were committed to appear before the Middlesex Assizes in June where they claimed they had bought the goods from an unknown person. The court was unable to prove burglary and theft and so Crockett was found guilty of receiving and sentenced to 18 months in prison while the other two received lesser sentences of 12 months and 9 months.[31]

In February 1939 Crockett, now living in Hammersmith at 116 King Street with Edith Emily Bull and listed in the 1939 census as working as a lorry driver. Edith was the daughter of a labourer from Dilton Marsh in Wiltshire. At this time, was implicated in the theft of a large number of gloves, valued at £432, from a glove factory in Yeovil. The gloves were found in a glove shop owned by Lewis Rutter in Hammersmith market and he was arrested. Rutter claimed he bought the gloves for £43 from a man called Reg Crockett. Rutter was committed for trial at Somerset Quarter Assizes charged with receiving stolen goods. [32]

At Rutter’s trial at the end of February, his defence asked Detective Bradford, the investigating officer from the Flying Squad if Crockett had twelve previous convictions for receiving stolen goods. Bradford agreed Crockett had a number of previous convictions. The defence then asked Bradford if Crockett was known in the vernacular as a copper’s nark (a police informer). Bradford refused to answer.

In October 1942, Crockett married Edith and was living in a large house in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey.[33] Reginald Godfrey Crockett died in Richmond-upon-Thames in May 1974 leaving a sum of £18,725 (£230,000 in today’s money).

It is hard to say if Crockett’s experiences as a soldier during world war one and the injuries he received impacted on his relationship with authority and his choices to commit crimes. However, there is no evidence that he received any help to overcome the trauma he had experienced or any attempt at rehabilitation. He spent approximately 18 years in prison. His career as a serial offender highlights the failure of a criminal justice system at the time which was based purely on retribution and prison.

After writing this article I was contacted by Reginald’s son Stanley who said he knew nothing about his father’s earlier life (see the comment section below ). As a result, Stan sent me the following:

“After World War Two Reginald started a small second-hand furniture business. He dealt with cancelled furniture orders, house clearances and auction buys. Some items were taken to the weekly sales at Gloucester market (Princes Hall) for auction. He had small premises in south-west London for storage/ sales. The business ran for more than 30 years. He certainly atoned for earlier misdemeanours(!), as from 1950 onwards he supported Mitcheldean & Abenhall parish ( in particular the Chapel), by donating money for church bells, proceeds of a furniture sale in the locality and several other donations. Notes in parish newsletters and grateful letters from rectors attest to these gifts. He passed away in 1974.”

I think this reinforces the idea we are products of our times, place and experiences and that as time moves on we can all change given the opportunity. At one time Reginald Crockett was in a very dark place. It is good to hear that he got himself out and built a new life as a family man and member of the community back where he grew up.

| Crime | Sentence | Conviction Date |

| Theft of Peas | Bound over | July 1908 |

| Letting off Fireworks | 8s costs | October 1908 |

| Entering an enclosed premise. | Bound over | 25 August 1911 |

| Stealing a watch | One month in prison | November 1912, |

| Theft | 42 days in a military prison | 3 September 1915 |

| Three accounts of going absent without leave and two accounts of theft | 12 weeks in a military prison | 17 April 1916 |

| Theft of some harnesses | 2 months in prison | July 1917 |

| Crime in Ebbw Vale | 6 months in prison | 1917/18 |

| Crime in Ebbw Vale | 6 months in prison | 1918 |

| Theft of some harnesses In Ebbw Vale | 6 months in prison | 12 September 1918 |

| Theft of a horse | 12 months with hard labour | 9 April 1919 |

| Receiving a stolen horse | 18 months in prison | 5 April 1920, |

| Theft of onions and forgery. | 9 months of hard labour | 26 April 1922 |

| Theft of wireless accessories and fraud. | 18 months in prison | 23 September 1924. |

| Burglaries and theft | 3 years in prison | October 1926 |

| Sheep theft | 3 years in prison | 2 July 1929 |

| Sheep theft | 4 years in prison | October 1934, |

| Receiving stolen goods | 18 months in prison | June 1936 |

[1] Gloucester Journal 1 August 1908. [2] Gloucester Journal 24 October 1908. [3] Gloucester Journal 23 November 1912. [4] Wikipedia. [5] Girard, Marion A Strange and Formidable Weapon: British Responses to World War I Poison Gas (University of Nebraska Press, 2008). [6]https://cwm-waunlwyd.gwentheritage.org.uk/content/catalogue_item/history-of-the-3rd-batt-the-monmouthshire-regt [7] Fold 3 via Ancestry. [8] Gloucester Journal 16 October 1915. [9] Fold 3 via Ancestry. [10] Ancestry [11] http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/ [12] Iren Wyatt, The transportees from Gloucestershire to Australia 1783-1842 (Bristol: Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1988) [13] Ibid and Ancestry. [14] The policy of appointing Honoraries was designed to enlist the interest and sympathy of ‘gentlemen’ of position and wealth by connecting them to the Regiment. They sat on advisory committees and attended social functions. [15] Gloucester Journal 21 July 1917. [16] Gloucester Journal 5 April 1919. [17] Gloucester Journal 12 April 1919. [18] Gloucester Journal 27 March 1920. [19] Gloucester Journal 10 April 1920. [20] Dean Forest Mercury 9 April 1920. [21] Ancestry. [22] Ibid. [23] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press 16 October 1926. [24] Gloucester Citizen 16 March 1929. [25] Birmingham Daily Gazette 28 June 1929. [26] Banbury Advertiser 4 July 1929. [27] Gloucester Citizen 2 August 1929. [28] The Tewkesbury Register, and Agricultural Gazette 24 August 1929. [29] Cheltenham Chronicle 11 August 1934. [30] Gloucester Journal 13 November 1934. [31] Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette 20 March 1936, 3 April 1936 and Friday 12 June 1936. [32] Western Morning News 8 February 1939. [33]Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser 2 January 1943.

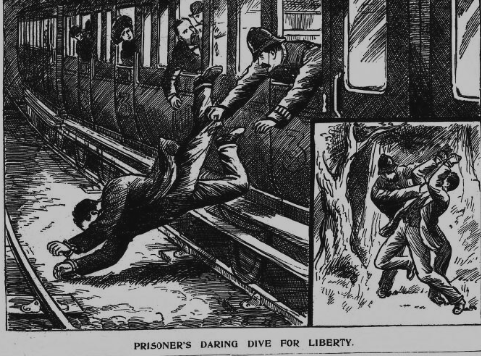

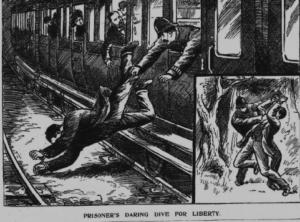

Illustrated Police News 17 October 1912 which gives an account of Boxer’s escape

Illustrated Police News 17 October 1912 which gives an account of Boxer’s escape