Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History reserve the copyright of this article but give permission for parts to be reproduced or published provided Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History are credited in full.

Introduction

The people who get ground down in wars get sung over and remembered. The state buried them after they were dead. We are not dead yet and the state is trying to bury us already.

Gwyn Thomas, Sorry for thy Sons (written in 1936)

The South Wales Miners’ Federation like all trade union organisations has as its fundamental duty the obligation to safeguard the working and living conditions of its members in all circumstances. The change from peace to war cannot lessen the obligation … we must preserve the complete independence of our organisation and avoid being drawn into an unhealthy collaboration which ignores class relations within modern capitalist society.[1]

Arthur Horner in an address to the South Wales Miners’ Federation (SWMF) Annual Conference of April 1940. (The Forest of Dean district became part of the SWMF in September 1940).

While they all realised that miners had suffered injustices in the past and were suffering injustices today, they should not do anything to the detriment of the effort that would mean the destruction of Hitler and all he stood for.[2]

Will Paynter (SWMF Executive) addressing Forest of Dean miners on 27 July 1941.

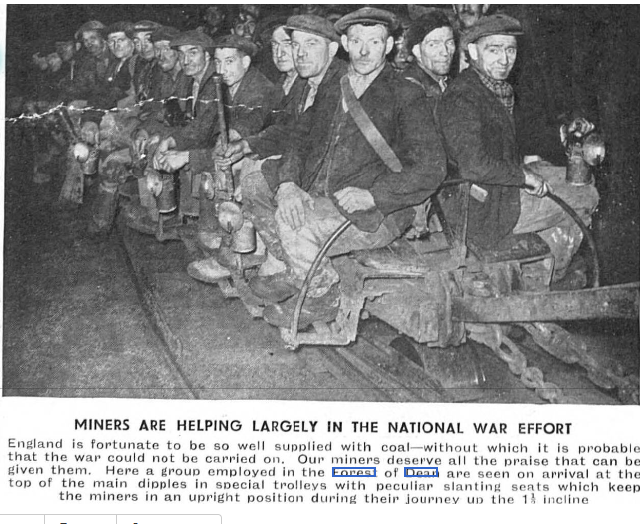

During World War Two, it was illegal to take strike action.[3] However, on 19 June 1941, the miners at Princess Royal Colliery in Bream in the Forest of Dean walked out on an unofficial strike without consulting their national or local trade union Executives or their full-time officials. This was followed by further unofficial strikes in other Forest of Dean pits in 1944. Many of these miners had relatives in the military and worked flat out to increase the coal supply for the war effort. This article explores the background of the strike and seeks to understand what motivated the men to take such drastic action.

The experience of the industrial strife of the 1920s and the severe economic depression which followed in the 1930s was crucial in moulding the attitudes that shaped the wartime behaviour of miners. The miners entered the war with a legacy of bitterness produced by the 1921 and 1926 lockouts, unemployment, and the impoverishment of their communities. The return to full employment brought about by the war did little to appease the miners, whilst wartime experiences tended to justify and reemphasise pre-war attitudes. During the war, work conditions deteriorated, and unfavourable wage comparisons with munition and factory workers led to resentment.

The development of draconian labour laws introduced in 1941 meant that existing miners were compelled to work in the coal industry by government legislation, with no option to join the military or move to better-paid work in the munitions industry. This suggested that miners were still being treated as second-class citizens and this inevitably led to a degree of resentment.

During World War Two, the coal industry experienced a decline in output. The reasons for this were complex but had little to do with the miners’ commitment to support the war effort. However, Government policy and measures to increase output placed the responsibility to increase productivity on a depleted, tired, ageing and often sick workforce.

When the decline in output continued and the pressure on the miners grew, strikes broke out. During World War two there were 514 stoppages between September 1939 and October 1944 in the South Wales coalfield alone.[4] Consequently, the miners were accused of being unpatriotic by the right-wing press and this was very hurtful and further impacted morale.

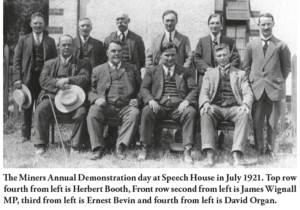

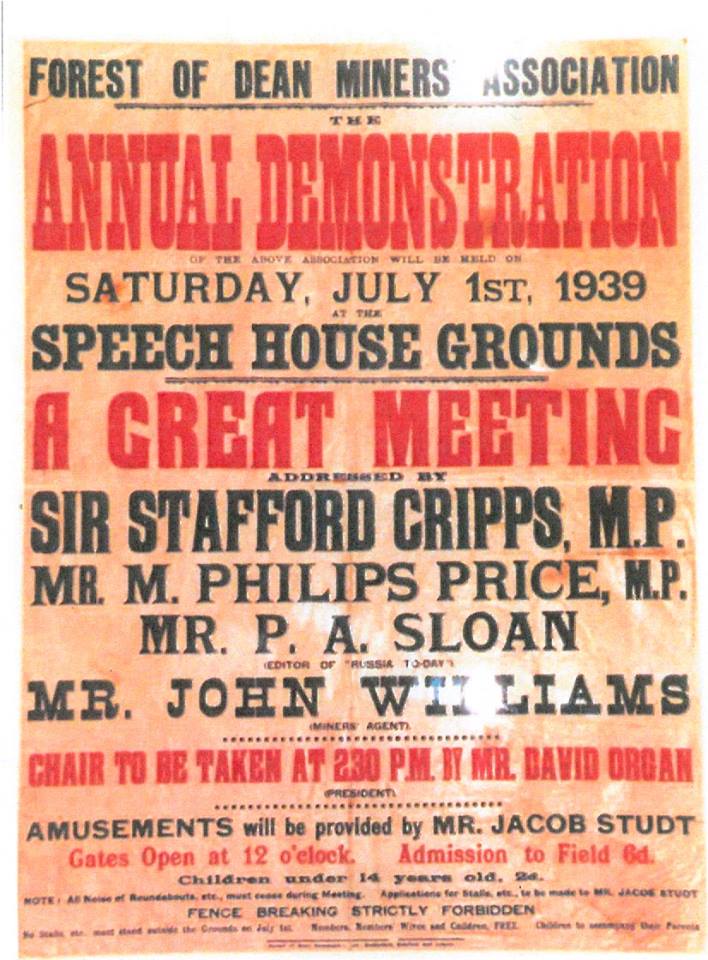

Forest of Dean Miners Association

The Forest of Dean Miners Association (FDMA) was the main trade union representing miners in the Forest of Dean and was affiliated with the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). Each district of the MFGB had a full-time miners’ agent whose responsibility was the day-to-day running of the association, recruitment, and negotiations with the employer. The agent for the FDMA from 1922-1953 was John Williams.

Williams’s job was to deal with disputes over collective and individual grievances, violations of the eight-hour day agreement, wages, coal allowances, unemployment pay, dismissals and reinstatements, overtime, weekend work, industrial accidents, compensation claims, etc.

The FDMA was made up of lodges organised around individual pits or villages. The lodges held an annual election for President, Secretary and Treasurer. In addition, pit committees were elected at each of the main pits to deal with day-to-day disputes and relations with the management.

Each lodge elected a delegate to attend the FDMA Council to which the agent was accountable and which met about four times a year. Every year, elections were held for the FDMA Executive Committee to include a President, Vice President, Secretary, Treasurer, Finance Committee, Political Committee and Auditors. An election could also be held if there was a challenger for the post of agent and the Council agreed. The Executive Committee held regular meetings jointly with FDMA delegates from the principal collieries. The agent would usually represent the FDMA at national or regional meetings.

FDMA Executive and Activists 1938-1947

| FDMA Member | Role | Colliery | Home |

| John Williams | Agent | Cinderford | |

| William Ellway | President | Norchard | Yorkley |

| Harry Morgan | Finance Officer | Princess Royal | Bream |

| Elton Reeks | Princess Royal | Bream | |

| Alan Beaverstock | Princess Royal | Bream | |

| Harry Barton | Delegate to SWMF | Northern United | Cinderford |

| Ray Jones | President | New Fancy and Princess Royal | Pillowell |

| Frank Matthews | Cannop | Mile End | |

| John Harper | Waterloo | Ruardean | |

| William Wilkins | Waterloo | Cinderford | |

| Charlie Mason | Northern | Brierley | |

| Wallace Jones | Safety Officer | Eastern | Cinderford |

| William Jenkins | Cannop | Broadwell | |

| Stanley Turner | Eastern | Drybrook | |

| Birt Hinton | Cannop | Berry Hill | |

| G D H Jenkins | Secretary | New Fancy and Princess Royal | Parkend |

| Harry Hale | |||

| C Brain |

In September 1940, it was agreed that the FDMA should join the South Wales region, whose President was Arthur Horner, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). The FDMA was renamed as the No. 9 area of the SWMF.[5] However, the press and Forest miners tended to continue still use the term FDMA when describing the miners’ union in the Forest because, at a local level, the union continued to function as before and so this convention will be used in this book. Harry Barton, who was Secretary of the Cinderford branch of the CPGB, was elected as the Forest of Dean delegate on the SWMF Executive.

Williams and the FDMA believed that it was necessary to fight against fascism and worked hard to support the war effort by encouraging miners to increase production and campaign against unnecessary absenteeism. At the same time, they remained loyal to the interests of his members, supported them in their conflicts with their managers and defended their trade union rights.

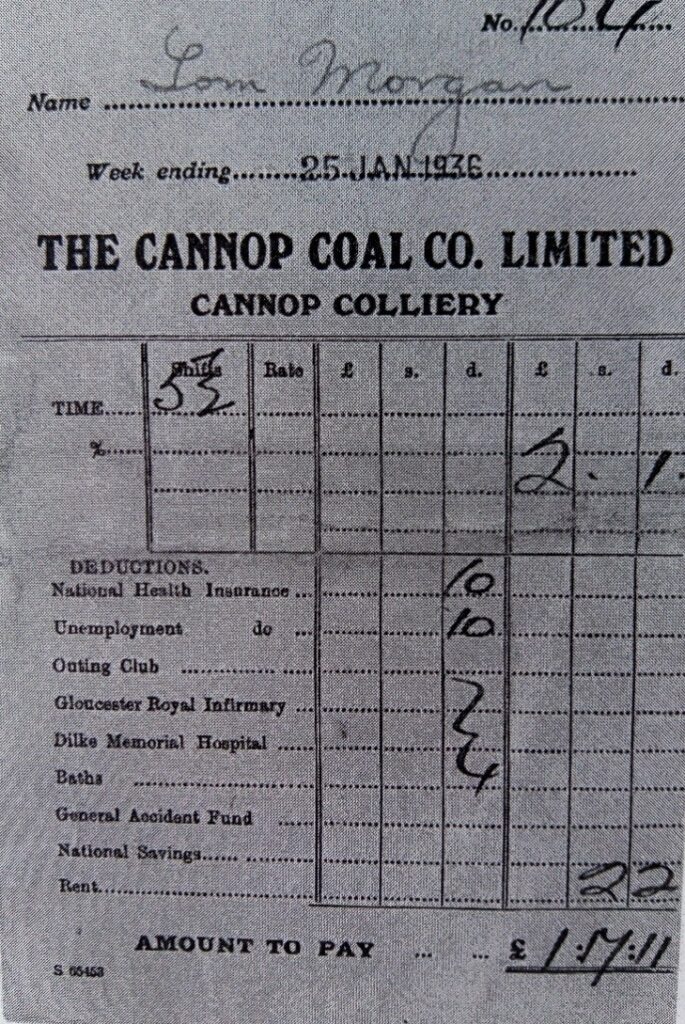

Wages

Since the 1921 and 1926 lockouts, the power of the MFGB had been undermined by its federated structure, which had returned power to the district associations. In some cases, such as in Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, local associations had been able to negotiate reasonable terms and conditions based on higher productivity. This was because the MFGB was tied into a national agreement that linked district wages to district profits. Any rise or fall in wages was calculated using a complex formula based on profitability in the district.

The MFGB and FDMA argued that the mining industry should now be nationalised and that there should be a single national union comprising all grades of workers with a single national agreement on wages and hours of work.

The highly skilled hewers who worked on the coal face, extracting coal, were paid by the ton of coal produced and earned the highest wages. Men working on timber work and road ripping were also paid on piece rates. Piece rate workers were paid a district minimum wage if their earnings from piece work fell below this minimum. Most other tasks in the pits were carried out by men or boys employed directly by the owners and they were paid a day rate which was usually less than the wage for the hewers. These men included the banksmen, enginemen, blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, pump men and surface workers. Also, on day rate wages were men and boys involved with the haulage of coal, maintenance of haulage roads, clearing roof falls, and attending to ventilation.

The average national wage for coal miners in 1938 was £2 15s 9d (about 11s per shift for a five-day week), ranking at number eighty-one in the official list of nearly one hundred trades.[6] In the Forest of Dean, the earnings of miners were lower than in most districts because of the poor condition of the pits, thin seams, problems with water and lack of investment.

The minimum wage for a hewer in 1938 in the Forest was 8s 9d and the average wage for a hewer on piece work in the Forest was about 10s a shift.[7] In the Forest in 1938, about 40 per cent of shifts were worked at the coal face. However, the remaining workers, including labourers, surface workers, craftsmen, etc, who were paid day rates, earned less than this.

The Coal Industry

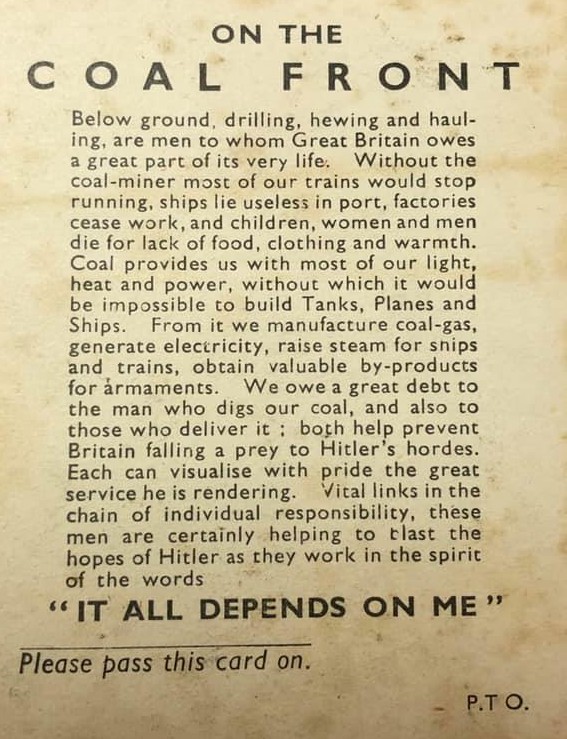

The ownership of the British coal industry in 1938 was highly fragmented. In the Forest of Dean, there were seven large collieries employing over 100 men managed by five colliery companies and about twenty-five small pits owned by a variety of small colliery companies or private individuals employing up to a maximum of about 50 workers each. Some of these small pits were small family concerns owned by free miners who operated under a system based on statutory rights unique to the Forest of Dean.

Free mining rights have been claimed from ‘time immemorial’ by any miner born in the Hundred of St Briavels (which roughly covers the area occupied by the Forest of Dean) who had worked a year and a day in a Forest pit. The Dean Forest (Mines) Act of 1838 confirmed the free miners’ exclusive rights to the Forest’s minerals This allowed any free miner to apply to the Deputy Gaveller, who represented the Crown, for a gale, which is a grant (right to mine) of a specific seam of coal or a deposit of iron ore or stone, in a specific location anywhere in the statutory Forest of Dean, provided he paid royalties to the Crown, the owner of the land.

The total of men employed in the Forest of Dean coalfield in 1938 was 4941.

Forest of Dean Collieries employed more than 100 workers in 1938

| Mine | Company | Location | Coal | Number of men | Dates of operation |

| Princess Royal | Princess Royal Colliery Ltd | Bream

|

Steam | 750 | 1840-1962

|

| Lightmoor | Henry Crawshay & Co. Ltd. | Cinderford | House

|

266

|

1840-1940 |

| Eastern United | Henry Crawshay & Co. Ltd. | Ruspidge | Steam | 831 | 1909-1959 |

| New Fancy, | Parkend Deep Navigation Collieries Ltd | Parkend | House | 333 | 1827-1944 |

| Norchard | Princess Royal Colliery Ltd? | Lydney | Steam | 222 | 1842-1957

|

| Cannop | The Cannop Coal Company Ltd | Cannop | Steam | 1152 | 1906-1960 |

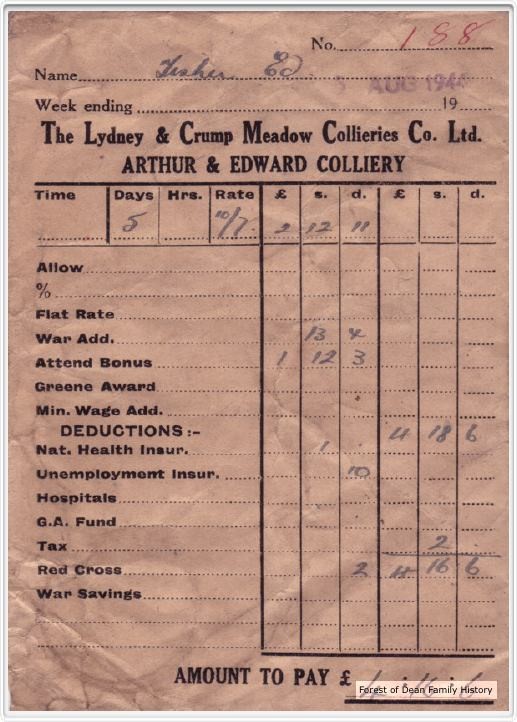

| Arthur and Edward (Waterloo) | Lydney and Crump Meadow Collieries Ltd | Lydbrook | Steam | 681 | 1841-1959 |

| Northern United | Henry Crawshay & Co. Ltd. | Cinderford | Steam | 457 | 1933-1965 |

| Total | 4692 |

The coal industry in the Forest lacked investment and was dominated by sectional interest and the short-term seeking of profits by the owners, which contributed to low productivity. Slow modernisation of production methods, decrepit haulage systems, inadequate underground layout and poor and costly distribution contributed to the stagnation. Inadequate training and the conservatism of managers, combined with poor industrial relations, made the situation worse.

The Second World War brought tremendous changes in the organisation of the industry itself and industrial relations within it, though the changes were not immediate. At the beginning of the war, the government established an indirect form of control of the coal industry by introducing a central council and district boards for its regulation, while ownership, control and day-to-day management remained in private hands.[8]

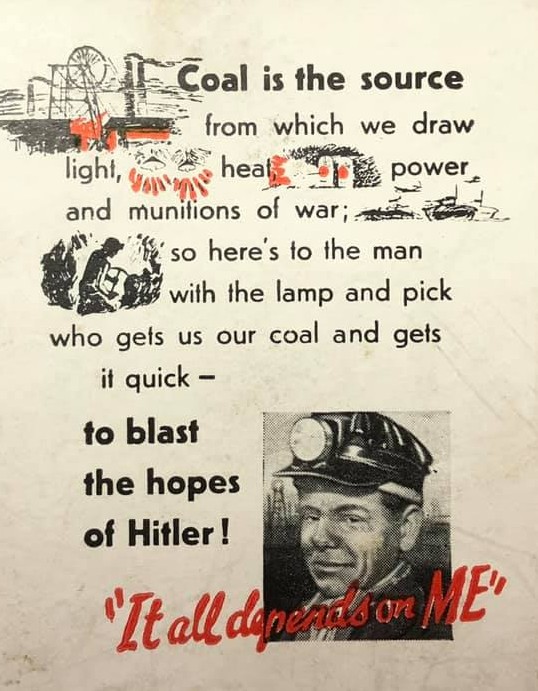

War Effort

The leadership of the MFGB and the FDMA and most miners were committed to supporting the war effort and trade union representatives were brought into war planning at a local, regional and national level. As soon as the war was declared on 1 September 1939, the government set up a meeting of the Joint Standing Consultative Committee (JSCC) made up of the Miners Association of Great Britain (MAGB), which was the organisation representing the colliery owners, and MFGB representatives to discuss the matter of increasing coal production.[9]

The government estimated that it would need to increase production by 30 to 40 million tons to bring it up to the level of 260 to 270 million tons deemed necessary to supply the munitions industry as well as industrial and domestic markets..

The MFGB made it clear that no extension of the working day should be agreed upon and any agreement on overtime should adhere to MFGB policy. The MFGB insisted that there be no reduction in the school leaving age (14), no extension of the employment of women and no employment of boys on the night shift. It was agreed to encourage unemployed or ex-miners to return to work and to reduce absenteeism.[10]

The MFGB argued Britain needed a unified coal industry under public ownership to increase production levels. During the war, the policies of the MFGB were based on the following priorities:

- The need to ensure coal production at sufficient levels to meet domestic and wartime needs.

- The need to minimise industrial conflict.

- The need to win significant wage increases for its members.

- The need to end district agreements and negotiate a national agreement for all mineworkers.

- The need to nationalise the mines.

At the start of the war, the MFGB and FDMA encouraged their members to support the war effort by working extra hard, working through holidays, working extra shifts, etc. As a result, in the first quarter of 1940, productivity improved. However, as the year progressed, it became clear that the intense work rate could not be sustained and productivity declined and did not recover for the rest of the war.

Manpower and Output in the British Coal Industry.[11]

| Year | Output of saleable coal in tons | Average number of miners | Output per miner per year in tons |

| 1938 | 226,903,200 | 781,672 | 290.4 |

| 1939 | 231,337,900 | 765,322 | 301.9 |

| 1940 | 224,298,800 | 749,165 | 299.4 |

| 1941 | 206,344,300 | 697,633 | 295.8 |

| 1942 | 203,633,400 | 709,261 | 287.1 |

| 1943 | 194,493,000 | 707,750 | 274.8 |

| 1944 | 184,098,400 | 710,203 | 259.2 |

| 1945 | 174,687,900 | 708,905 | 246.4 |

Manpower and Output in the Forest of Dean Coal Industry[12]

| Year | Output of saleable coal in tons | Average number of miners | Output per miner per year in tons |

| 1938 | 1,349,500 | 4,941 | 273.1 |

| 1939 | 1,312,700 | 4,838 | 271.3 |

| 1940 | 1,204,200 | 4,451 | 270.5 |

| 1941 | 1,071,800 | 4,166 | 257.3 |

| 1942 | 1,021,000 | 4,216 | 242.2 |

| 1943 | 966,600 | 4,339 | 222.8 |

| 1944 | 926,000 | 4339 | 213.4 |

| 1945 | 873,100 | 4298 | 203.1 |

The difference in output per miner between the national and Forest coalfields was due to the poor conditions in the Forest, such as thin seams, cramped conditions and water which required constant pumping, combined with a lack of investment and the slow introduction of coal cutting machinery and mechanical conveyors.

About half the seams worked in the Forest were under four feet and none over five feet, whereas in other districts, 20 per cent of the seams were over 5 feet. In the Forest, most collieries still used timber supports and men and horses to move coal.[13] In some pits in the Forest, most of the undercutting and loading of coal was done by hand and the amount of coal cut and moved using machines was much less than in other districts. [14]

The use of Machines for Cutting Coal in Forest of Dean (FOD).[15]

| Year | No of collieries using machine cutting in FOD | No of machines in use in FOD | Percentage of coal cut by machine in the FOD | Percentage of coal cut by machine nationally |

| 1938 | 5 | 19 | 21 | 56 |

| 1939 | 7 | 25 | 26 | 59 |

| 1940 | 6 | 27 | 34 | 61 |

| 1941 | 5 | 26 | 42 | 63 |

| 1942 | 6 | 29 | 47 | 64 |

| 1943 | 6 | 33 | 55 | 67 |

| 1944 | 53.7 | 80.2 |

The use of Machines for Loading and Conveying of Coal[16]

| Year | No of collieries using machines to load and convey coal in FOD | No of machines in use in FOD | Percentage of coal loaded and conveyed by machines in the FOD | Percentage of coal cut by machine nationally |

| 1938 | 3 | 18 | 21 | 54 |

| 1939 | 4 | 23 | 28 | 58 |

| 1940 | 5 | 30 | 32 | 61 |

| 1941 | 6 | 29 | 34 | 64 |

| 1942 | 6 | 36 | 33 | 65 |

| 1943 | 6 | 37 | 42 | 66 |

The decline in number of miners was due to:

- Men joining the forces.

- Leaving to find better-paid work with better conditions in other industries.

- Deaths (accidents and natural).

- Retirement,

- Sickness,

- Lung disease

There continued to be the recruitment of juveniles (under 14-18), but they could not replace the loss of older skilled workers. However, later in the war, recruitment was bolstered by some men returning from the armed forces and other industries, volunteers, and those sent to the mines by ballot (see discussion of Bevin Boys below).

Build up to War

When Hitler broke his word and occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Britain and France gave a guarantee to Poland to support its independence. As a result, on 6 April, Britain agreed to a formal military alliance with Poland; however, it refused to form an alliance with Russia.

In May 1939, plans for limited conscription applying to single men aged between 20 and 22 were given parliamentary approval in the Military Training Act. This required men to undertake six months of military training and then to be transferred to the Reserve. Some 240,000 men registered for service including some miners.

On 23 August, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a Treaty of Non-aggression. In the Forest of Dean, this resulted in an accusation from some members of the Labour Party of treachery by the Soviet Union. On 26 August, Morgan Philips Price, the Forest Labour MP, expressed this view at the annual carnival and fete of the Forest of Dean Labour Party in Bream, chaired by Albert Brookes.

However, much they blamed Mr Chamberlain and the others, nothing could absolve Russia from the treachery to Poland.[17]

The CPGB leadership strenuously denied this accusation, arguing that the Soviet government had been compelled to act when the French and British governments refused to enter a formal alliance with them against the Nazis.[18]

On 1 September, Hitler invaded Poland and on 3 September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland through its eastern border.

As a result of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Comintern characterised the war as an imperial conflict between two more or less equally culpable blocs of capitalist nations. (The Comintern, also known as the Third International, was a political international organisation that existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated for world communism. It was founded in Moscow in March 1919 with 52 delegates from 34 communist and socialist parties from across the world.)

However, some British CPGB members ignored this policy and argued that the CPGB should support the war effort to defeat fascism. These included senior members such as Harry Pollitt and Arthur Horner, who were then sidelined by the CPGB leadership.

When the war was declared, parliament immediately passed a more wide-reaching conscription measure, the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, which imposed conscription on males aged between 18 and 41, all of whom had to register for service. Those medically unfit were exempted, as were others in key industries such as farming, medicine, and mining. Most miners over the age of 23 were exempted, although, for some less-skilled jobs in the mining industry, the exemptions were only for those over 30.

Some miners were eager to get out of the mines and volunteered for the forces. As a result, by mid-September, 27,000 men had left the mining industry for the military, civil defence or munitions work and this immediately impacted the level of coal production.[19] At the end of October, the MFGB requested that the government reduce the reserve age in some grades of the mining industry to eighteen because of the need to increase coal production by at least 30 million tons.[20]

In some pits in the Forest of Dean, men of military age and no experience in mining applied for work in the pits and some of the existing miners believed that this was to avoid conscription.[21] As a result, stoppages were threatened and on Saturday 9 September, a meeting of the FDMA Executive was held at Speech House, after which Williams told the press:

What angers the miners is the suspicion that these men would have not come near a colliery but to get work but for the fact that the mine offered a chance to avoid military service.[22]

Another meeting was held on Saturday 16 September and it was agreed to make representations to the colliery owners over the matter. Consequently, the owners agreed that, as far as reasonably practical, men who had entered the mines during the war or immediately preceding the war would be withdrawn. In addition, any miners who had recently left the industry should be given priority over those with no experience.[23]

Wages

The MFGB argued that despite the promise by the government to reduce profiteering, the cost of living was rapidly rising.[24] The MFGB insisted that the MAGB agree that the JSCC discuss issues to do with the cost of living, wage rates, hours and safety on a national as opposed to a district basis. As a result, in September, the MFGB decided to use the JSCC to attempt to break out of the existing district agreements and negotiate a new national wage agreement. At the meeting of the JSCC on 28 September, the MFGB put in a claim for an immediate flat-rate increase for all miners in the form of a war bonus of 1s a day for men and 6d for boys under 18, as an interim settlement until the end of October. The MFGB demanded that wages should be increased from then on according to the rise in the cost of living.[25]

In response, the MAGB offered a pay rise of 8d for men and 4d for boys to cover the period from 1 November to the end of the year.[26] The award was termed as a war bonus and would be merged with any rise in wages from district agreements and paid for by increasing the cost of coal.

At the MFGB conference on 2 November, there was some reluctance among the areas with higher productivity to accept a flat rate national agreement, as they believed they would be better off with district agreements. Horner, who was on the negotiating committee, argued in favour of the offer:

Let us try to find a formula which will at least ensure this, that at the worst … the most backward district, including the Forest of Dean … shall have the same advantage as Yorkshire and the same as Nottinghamshire. In fact, they needed it more with an average wage of 11s a day as against an average wage of 15s a day … I want a national organisation. I believe in national control of the wage policy. I believe in using every possible situation to unify … the miners of this country. I do not think it is right that the accident of geography should determine that Welsh miners should get two-thirds of what miners in the Midlands are getting.[27]

The voting was 342,000 in support of the agreement and 253,000 against it, resulting in the acceptance of the offer.[28]

Increasing membership

At the start of the war, the membership of the FDMA was low, but by December, it had rapidly increased. Williams informed his members that in January they would receive a small pay rise resulting from the district agreement due to the increasing profits of the local colliery companies.[29]

One of Williams’s tasks was to represent miners if they felt they had been wrongly conscripted. This could happen if a miner changed his grade after registration.

The FDMA was aware that there was considerable dissatisfaction among its members over those non-union men who received all the benefits it negotiated. Consequently, the FDMA demanded that the owners assist them in securing 100 per cent union membership in Forest collieries to prevent any stoppages over the issue of non-unionism.[30]

The Cost of Living Formula

The increase in the cost of living meant that workers in other industries were also demanding and receiving pay rises. As an example, in December 1939, West Dean District Council agreed to a flat rate increase for its employees of 3s a week.[31]

At the end of 1939, the MFGB threatened to hold a national strike ballot unless the MAGB and the government agreed to a formula to link wages to the rise in the cost of living. In January, the MAGB and government quickly gave way and conceded another national cost of living increase of 5d a shift for men and 2.5d for boys to be backdated from 1 January 1940. On 25 January 1940, this offer was accepted by the majority of delegates at an MFGB conference.[32]

In addition, the MFGB negotiated a flat rate addition of 0.7d per shift for adult workers corresponding to a variation of one point in the cost-of-living index, subject to a three-month review. The offer was referred to the districts and, by the first week in February, the majority, including the Forest of Dean, voted to accept it.[33]

The agreement between the MAGB and MFGB meant that district wage negotiations would continue as before, but any additions due to the war and the cost of living would be agreed upon nationally.[34] This meant that wages in areas like the Forest of Dean would continue to lag behind the more productive areas. However, as the wage increases at this time were in response to the increasing cost of living, they made little difference to the miners’ incomes in real terms.

In March 1940, Forest of Dean unemployment of insured workers was down from 1262 in March 1939 to 450 in March 1940, of whom about 100 were women and girls. In Cinderford, unemployment decreased from 589 to 150 as some unemployed miners joined the forces or drifted away into better-paid work in the munitions industry.[35] Many of the remaining unemployed workers were elderly or physically unfit for colliery work. Consequently, the Forest colliery owners started to run into difficulties recruiting skilled and healthy miners.

Deaths and Injuries

During World War Two, the UK’s coal mines experienced a significant number of accidents and fatalities, though not as severe as those in other industries like munitions factories or the military. Between the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939 and the end of 1944, approximately 4,363 miners were killed in coal mining accidents across the United Kingdom. In addition, 15,240 miners sustained serious injuries during this period. [35b] These statistics underscore the significant human cost borne by coal miners who played a crucial role during World War Two, supplying coal for the war effort.

In the Forest of Dean, there were fourteen deaths during World War Two in its mines and many serious accidents. The first death was Charles Screen, age 39, who was killed at Princess Royal Colliery on 24 September 1939. Further deaths will be listed in boxes throughout the text with details taken from Dave Tuffley’s database of deaths in Forest mines, Roll of Honour, available on the Forest of Dean Local History website.

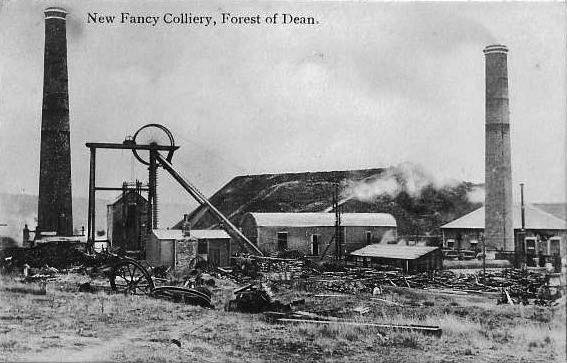

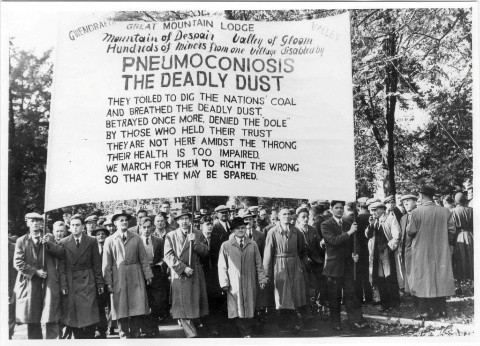

Beyond immediate accidents, many miners suffered from long-term occupational diseases. In South Wales alone, between 1937 and 1948, over 2,000 miners died and nearly 38,500 were permanently disabled due to silicosis and pneumoconiosis, diseases caused by prolonged exposure to coal dust. [35c]

Silicosis

Mining communities have always been aware of the devastating consequences of lung disease caused by breathing dust. It is now known that there are several different types of lung diseases caused by breathing dust in coal mines, but silicosis was the first one to be recognised as an industrial disease.

Silicosis is a result of breathing in dust from rock containing silica, often produced because of drilling or blasting operations when creating roadways in the mines. The disease meant miners could become disabled and unable to work at a relatively young age, sometimes as young as forty. They then could suffer a long, painful early death, leaving grieving families with no compensation or even recognition that the disablement and death were a result of working in a mine. Forest miner Albert Meek recalled how his father suffered from silicosis:

which was then called ‘colliers’ asthma,’ never got anything for it. I often think about it, my father was rasping for years before he died and he died before he was fifty.[36]

The symptoms of silicosis usually take many years to develop and problems sometimes do not develop until after exposure and can then get much worse. In most cases, exposure for at least 10-20 years is required to cause the condition, although in a few cases, it can develop after 5-10 years of exposure or, in rare cases, after only a few months of very heavy exposure.

Silicosis was first recognised as an industrial disease for compensation purposes in the 1928 Various Industries (Silicosis) Scheme. Under this Scheme, the applicant for compensation had to prove that they had been working in silica rock containing 50 per cent or more free silica, had been blasting, drilling, dressing or handling such rocks and had already been disabled by silicosis.

This was the first step in a long battle with the colliery owners, the government, and their allies in the scientific and medical establishment to recognise the various types of lung disease caused by dust.

The FDMA encouraged miners with lung disease to apply for a medical assessment and compensation; however, there was no systematic screening, so the prevalence of the disease was underreported. The deaths listed in the tables below are taken from reports of coroners’ courts in the local newspaper and do not reflect a true picture of the prevalence of the disease.

Deaths from silicosis in the Forest of Dean, which were reported in the local newspapers in 1939 and 1940[37]

| Name | Age | Date of Inquest | Home | Colliery |

| Charles Hook | 52 | Feb 1939 | Ruspidge | Eastern |

| William Baglin | Mile End | |||

| Alfred Chamberlain | 63 | Nov 1939 | Cinderford | New Fancy |

| Thomas James Davies | 66 | April 1940 | Pillowell | |

| William Charles James | 53 | November 1940 | Bream | Princess Royal |

Forest of Dean Coal Production Committee

In April 1940, the government established a National Coal Production Council made up of representatives from government departments, the MFGB and MAGB. On 23 May, members of the FDMA and the Forest colliery owners met with Lord Portal in Gloucester to discuss ways of improving productivity.[38] As a result, the FDMA helped set up a Forest of Dean Coal Production Committee (FODCPC) with owners and workers’ representatives to discuss ways of increasing output in conjunction with the pit committees. In addition, each pit had its own production committee made up of managers and FDMA members Charlie Mason at Northern.

The FDMA representatives on the FODCPC were Wallace Jones (Eastern), William Jenkins (Cannop), Harry Morgan (Princess Royal), Ray Jones (New Fancy) and Harry Barton (Northern).[39] The FODCPC agreed to work with the FDMA pit committees to urge the men to avoid unnecessary absenteeism and for those who worked the 2 pm to 10 pm shift to work a sixth shift on Saturday afternoon. Some workers already worked a Sunday night shift to prepare the ground for the Monday morning shift. The committee also agreed to urge the men to work through the summer without taking a holiday. After the first meeting, Williams told reporters:

The first subject that we have tackled is that of voluntary absenteeism which relates to men losing time for their convenience. It has been found more time is being lost on Sunday nights. An appeal is to be made by the Forest Miners’ Association for all workmen to work every shift possible. Notices are to be put up at the pitheads informing the men they are expected to lose as little time as possible and announcing the decision of the Committee relating to the afternoon shift week.[40]

However, after a ballot of FDMA members, it was agreed that working a six-shift should be voluntary and only if an additional allowance was paid. In the House of Commons, Philips Price asked the Secretary of Mines, David Grenfell, if he was aware of this grievance over the additional allowance. Lady Astor complained that there was no reason why the men should be paid. Some Labour MPs asked Astor: “What do you know about it?” Grenfell informed Astor that it was customary for the men to be paid an extra allowance for additional shifts and the matter was being dealt with by negotiation between the local associations and the local colliery owners.[41]

Ernest Bevin

In the second week of May 1940, the Germans invaded Holland and Belgium, resulting in the resignation of Chamberlain and the formation of a Coalition government with Churchill as Prime Minister and Clement Attlee as Deputy Prime Minister. Churchill’s war cabinet consisted of five members, including two Labour MPs, Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood. Other Labour members held ministerial positions, the most important of whom was Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour and National Service. However, Chamberlain, as leader of the Conservative Party, remained a member of the government and continued to have many supporters in parliament until his death in October 1940.

Bevin’s standing as leader of Britain’s biggest trade union, the Transport and General Workers Union, was intended to deflect the kind of opposition to the control of labour that had been such a feature of the First World War. However, the measures introduced during the Second World War were similarly draconian and the Emergency Powers Act and Defence Regulations provided the government with all the power it needed to direct and control labour. On 10 July 1940, the government introduced a regulation allowing Bevin to ban strikes and lockouts and to refer any dispute to compulsory and binding arbitration. Bevin established a Joint Consultative Committee of seven employers’ representatives and seven trade unionists to advise on the conduct of the war effort on the home front.

An apprehension that an invasion was imminent was widespread and so the Forest miners collectively took their responsibilities seriously and continued to work flat out. The FDMA continued to do everything in its power to maintain and improve the output of coal and, at the same time, sought to ensure the continuation of safety provisions and the protection of wages and conditions of its members.

In May 1940, it was announced that Lightmoor colliery was to close mainly because of the exhaustion of the coal seams and the drift of men from the colliery to the wartime factories. The output at this time was only 118 tons a day. Most of the 172 men were absorbed in the Crawshay’s other collieries, Eastern United and Northern United. The last wagon of coal to leave the pit was dispatched on 5 June.

The government was concerned that more miners would leave the industry to find better-paid work elsewhere. As a result, in June 1940, the government introduced a regulation preventing miners from seeking alternative employment and preventing the conscription of unemployed miners.[42]

Dunkirk

The MFGB conference in July 1940 was probably the bleakest in its history and had only one concern: the defeat of the British army at Dunkirk and the success of the Nazi military forces in Europe.

Williams was elected to represent some of the smaller regions on the MFGB Executive Council and, as a result, worked closely with Horner and other left-wing members of the Executive in developing a strategy on how to respond. On 16 July 1940, the SWMF and FDMA jointly presented the following resolution to the conference, which was proposed by Horner and seconded by Williams:

This Conference of the Mineworkers’ Federation of Great Britain deplores the situation in which the British people find themselves largely in consequence of the policy pursued by the Chamberlain Government; a policy which has resulted in strengthening the potential enemies of Britain whilst weakening the forces who had common interests with us in preventing aggression. The Conference pledges itself to do everything within its power to assist in maintaining the freedom of the British people and to ensure that neither occupation of British territory nor capitulation to the forces of aggression shall take place. It considers it fundamental and essential to success in this effort that all those who, led by Chamberlain, pursued the policy which has created this situation shall now be retired from all offices in the Government so that a Government more representative of the people of this country shall be installed forthwith.[43]

The motion provoked a long and heated debate, with the main point of contention being that the resolution could be interpreted as a motion of no confidence in the government. In the end, the conference agreed to a similar but weaker motion, which did not explicitly criticise Chamberlain or the government.

One result of the French armistice was a contraction in the demand for export coal from France. Nationally, the number of men employed in the mines decreased and in some areas, such as South Wales, there was significant unemployment and poverty. As a result, in October 1940, despite objections from the MFGB, the government removed the restrictions on the conscription of unemployed miners and any miner who was surplus to requirements. Consequently, more skilled men were lost to the mining industry.

Demand for Coal

1941 was characterised by the increasing crisis in the mining industry as shortages of coal became a concern and demands upon the labour force grew. The conversion to a war economy led to an expansion of demand for coal by the munitions industries, while at the same time, miners were drifting away from the industry into work with much better pay and conditions, such as munitions. The pressure on the workforce to increase productivity led to discontent and, in some cases, strikes.

The MFGB was very concerned about how the crisis in the production of coal would impact the war effort. In December 1940, the MFGB requested that the Labour Party and TUC consider supporting their demand for the nationalisation of the mines, arguing that a nationalised industry with good pay and conditions was needed to retain the workforce. However, on 31 January, the TUC and Labour Party rejected this suggestion but decided to promote a scheme of national control in which the mines remained in private ownership but their finances were controlled by the government.[44]

In early 1941, the Ministry of Labour established National Service Tribunals for the coal mining industry in each district to decide which men should be retained in the mines or released to the munitions industry or military. In the Forest of Dean, the Tribunal was made up of J E Rees, from University College, Cardiff, as Chairman, with Percy Moore and David Lang as the employers’ representatives and Williams and William Jenkins as the FDMA representatives.[45] In most cases, only young, inexperienced miners and unemployed miners from districts affected by the decline in the export trade were released.

Food

One of the tasks of the District Councils was to set up Food Committees to monitor the distribution of food. These committees were made up of retailers and consumers, including miners and miners’ wives.

One of the issues impacting productivity in the mining industry was the shortage of food for the miners, in particular sugar and cheese. This was acknowledged on 4 January 1941 when the West Dean Food Committee heard complaints from miners’ wives that they could not get suitable food for their husbands’ packed lunches. The discussion arose after the announcement by the Divisional Food Officer, L P Hullett, that permits issued for extra sugar for miners were to be withdrawn even though permits were still available for local tin plate workers.[46] The Chairman, L C Porter, said:

They have to get coal for steam. Without steam, you cannot generate electricity, and without electricity, you cannot have munitions. The miners must, therefore, be properly cared for.[47]

It was reported by Thomas Phillips, a miner from Princess Royal, that there was discontent at his colliery over the removal of permits for sugar and the scarcity of cheese. He said, as far as the miners were concerned, the situation was very serious. Miner’s wife, Cindonia Clutterbuck from Bream, said: “They cannot possibly realise what the life and the running of a miner’s home really is”. Porter pointed out that munition factories have canteens where the workers can get good, cheap food in addition to their rations and this is not available to miners in the Forest of Dean. It was agreed to raise the matter with Morgan Philips Price, the local Labour MP, and the Ministry of Food.[48]

The issue of food for miners came up again at the West Dean Food Committee meeting on 6 February 1941, when it was revealed that munitions workers were getting extra rations of meat in their canteens. Clutterbuck claimed that no cheese had been available in the Bream area for three weeks. This was of particular concern as cheese was the staple food for miners’ packed meals. Despite this, it was reported to the meeting that an application by the Committee for cheese to be made available to miners was turned down by the Ministry of Food in Bristol.[49] This situation was aggravated by the increase in the cost of food and the cost of living had gone up by 42 points by February 1941.

Absenteeism

Resentment among miners was exacerbated when, on 28 March 1941, accusations of slacking and absenteeism were made by an anonymous local colliery owner in the Dean Forest Mercury. The managing director of another Forest of Dean colliery company claimed that men are avoiding working a full week to evade paying income tax and added: “The fact is that they do not want to work a full week”.[50]

However, the managing director of another Forest colliery company said absenteeism was a problem, but no worse than before the war. He claimed that illness, accident and voluntary absence from work in his group of pits was running at about 13 per cent and of these, about 6 per cent had a just cause such as holidays, lack of equipment, etc. He added that the main problem was the migration of skilled miners to other industries.[51] A spokesman for the miners replied that the accusation:

that men are deliberately losing time and thereby reducing their wages so as to avoid paying income tax is too absurd to be treated seriously.[52]

Essential Work Orders

The government was reluctant to increase its control of the coal industry and attempted to solve the crisis in productivity by placing restrictions on the movement of workers out of the coal industry. In March 1941, the government introduced an Essential Work Order (EWO), which placed a statutory requirement on all skilled workers to register and tied workers to jobs considered essential for the war effort, such as munitions and agriculture. The EWO empowered the Ministry of Labour to prevent workers from leaving the industry without permission and to direct skilled workers wherever they were most needed. The EWO made persistent absentees the subject of the discipline of the National Service Officer. On 8 April, the government announced the mining industry would be subject to EWOs.

The authorities continued to cite absenteeism as one of the main causes of falling output in the coal industry and applied increasing pressure on the local production committees to resolve this issue. The EWO empowered the authorities to impose a fine of up to £100 or three months imprisonment and the removal of the exemption from military conscription status on any miner found to be guilty of persistent absenteeism without just cause.

The accusation that absenteeism was the source of low productivity did not stand up to scrutiny because attendance was rising. The main cause was falling productivity in the older coalfields, where conditions were poor and lacked investment, such as the Forest of Dean, which was not offset by rising productivity in the more productive regions.

Also, behind the statistics lay the legacy of the inter-war years. The labour force was getting older. Some miners were disabled and suffering from lung disease and were unable to work the long hours expected of them, resulting in sickness and absenteeism. The Dean Forest Mercury was regularly reporting the deaths of middle-aged miners from silicosis. In May 1941, the Forest of Dean Coroner reported:

These cases are inevitable in coal mining districts and I am afraid there will be many more.[53]

Deaths from silicosis in the Forest of Dean, which were reported in the local newspapers in 1941

| Name | Age | Date of Inquest | Home | Colliery |

| Alfred Henry Cole | 58 | April 1941 | Bream | Princess Royal |

| William Leyshon | 62 | Sept 1941 | Cinderford | Eastern |

Moreover, the population was declining in the mining areas and most miners were reluctant to let their children go down the pits. Accusations by the authorities and in the media that the miners were not pulling their weight led to resentment and discontent within the mining communities throughout the country.

At the MFGB conference in May 1941, the delegates initially opposed the EWO scheme, arguing it was a form of ‘statutory slavery’. Then they agreed to support the scheme on condition that the government consider their request for a Joint National Board to cover all problems facing the industry, a guaranteed weekly wage and the end of non-unionism. The government failed to respond and, under protest, the conference finally agreed to accept the scheme unconditionally.

New Fancy

One of the oldest of the large collieries in the Forest of Dean was New Fancy and it was the last large house coal colliery in the Forest of Dean. It was likely that Thomas Deakin, who was the owner of New Fancy, was one of the colliery owners mentioned above who complained about absenteeism because, in May 1941, he threatened to close New Fancy unless productivity increased and absenteeism was reduced. Deakin claimed that absenteeism at New Fancy over the past four months was running at about 15 per cent, including voluntary and non-voluntary absenteeism. [54]

However, he failed to mention that its output was steadily declining because many of the better-accessed seams had been worked out, the work conditions were very poor and he had made little investment in the pit, which could have improved productivity. House coal colliers were highly skilled and used to working in difficult conditions and many of these men were approaching the end of their working lives. As a result, Deakin was having problems recruiting and maintaining a skilled workforce and, because of the conditions, absenteeism was higher than in the other pits. On top of this, about half of absenteeism was not voluntary but due to other reasons such as holidays, disputes, machinery breakdown, lack of tubs, etc

The issue of absenteeism was not confined to the Forest of Dean and had become a national issue. As a result, the MFGB made an agreement with colliery owners that a bonus of 1s a shift for men and 6d for boys should be paid to men working a full week. The scheme would be introduced across the country at the beginning of June. William Lawther, the President of the MFGB, stated the agreement included a provision that if a man was absent due to illness (confirmed by a medical certificate), an accident or having to attend to trade union duties, air raid warden or home guard duties, then this should not affect the bonus. However, he added:

The man who stayed away from work without good reason should be dealt with. The miners realised that every ton of coal was required for the war effort.[55]

At the same time, an appeal was made to the district production committees to increase output to prevent a shortage of fuel for the war effort and the civilian population in the winter.[56] Also, the government announced that the recent agreement that workers in most industries should take a week’s holiday did not apply to miners, who were expected to work throughout the summer without a break. However, in the Forest, Williams, the FDMA and the pit production committees made it clear that they would refuse to get involved with disciplining their own members over absenteeism.

Strike at Princess Royal Colliery

The Forest miners continued to work long hours to support the war effort. Some Forest miners had already agreed to work on Sunday night to prepare the coalface for the next day, so Monday morning could become an ordinary coal-producing shift. The matter of voluntarily working a sixth shift on Saturday afternoon was put to a ballot with a recommendation from the FDMA Executive to accept the proposal. Consequently, most Forest miners voted to accept the proposal but only on the basis that it was voluntary..

As a result, the FDMA made an agreement with Princess Royal and Norchard managers that an extra shift would be worked and paid at a rate of time and a half. It was agreed that working the sixth shift should be voluntary and the FDMA pit committee would endeavour to encourage full attendance. Despite the efforts of the FDMA, the agreement was only partially successful as there tended to be higher levels of absenteeism on this shift compared to others.

On the evening of Thursday 19 June, miners at Princess Royal Colliery walked out on an unofficial lightning strike over the payment of the new one-shilling attendance bonus, which the management claimed was dependent on working the Saturday afternoon shift. The miners claimed that because they had made an agreement with the managers that working the Saturday afternoon shift was voluntary then their absence on that shift should not disqualify them from getting the bonus. The FDMA representatives at the pit immediately contacted Williams, who advised the men to return to work and agreed to negotiate with the managers over the matter of the bonus. However, the men decided to stay out on strike.

Williams and a deputation of Princess Royal miners met Percy Moore, the managing director, on Friday morning, but could not get an agreement. Williams addressed a mass meeting of the miners later in the day and gained permission from them to negotiate an immediate return to work, provided the Princess Royal management agreed to pay the full bonus owed and to refer the dispute to the Conciliation Board. Unfortunately, Moore rejected these demands outright.

On Friday night, Williams received a phone call from the Mines Department urging him to do everything in his power to bring about a settlement. It is likely that Moore also received a similar phone call as the next morning, he invited Williams to meet him at Old Dean Hall. Moore agreed on a compromise, which involved the ending of the Saturday afternoon shift and made some proposals involving arbitration. Williams responded by agreeing to discuss these with the pit committee and the FDMA Executive on Sunday morning.

Williams met Moore again at noon on Sunday, when a settlement was negotiated, which meant that the Saturday afternoon shift would be abolished and the question of the bonus owed to the men would be referred to arbitration. Later in the day, Williams put the proposed agreement to a mass meeting of Princess Royal miners at Knockley Wood, which was presided over by Harry Morgan from the Princess Royal pit committee. The meeting was also attended by the FDMA Executive members and addressed by Arthur Horner and W J Sadler (President and Vice-President of the SWMF) and William Jenkins from Cannop. The men agreed to the proposal and returned to work on Monday morning. Subsequently, the management agreed to pay the bonus owed to them.[57]

Williams told the Dean Forest Mercury that in his view, abolishing the Saturday shift would increase productivity as the men needed time to recover over the weekend and that:

The company made a mistake in withholding the bonus. If they thought that the men were not entitled to it, they should have referred it to the machinery set up for dealing with disputes like this. The Company miscalculated very badly in the whole affair.[58]

No one was prosecuted for taking the strike action mainly because the government did not want to inflame the situation. However, the problems associated with shortages of skilled labour and an ageing and exhausted workforce continued to impact productivity.

Five Point Programme

On Monday 23 June 1941, Bevin announced that he was introducing a five-point programme to increase the production of coal. He added that about 690,000 miners were employed at present and another 50,000 were needed to increase production, but argued that there was no need for miners to be returned from the military. The five points included:

- Management to concentrate on maximum production.

- Absenteeism must stop and those not pulling their weight could have their exemption withdrawn.

- Men available in mining districts must be taken back into the industry.

- Ex-miners working in other industries must be returned to the pits.

- No more miners to be called up.[59]

The MFGB and FDMA agreed to cooperate but added that it would be necessary to release skilled miners from the armed forces to increase production. In July 1941, Bevin introduced compulsory registration at employment exchanges of ex-coalminers who had been employed in the industry since 1935 with the view of sending them back to work in the mines.

Holidays

The Mines Department continued to press the miners to work through their holiday and to work six shifts a week, which included Saturday afternoon.[60] On 4 July 1941, the local colliery owners met with the FDMA Executive, who agreed to try and persuade the miners to give up their one week’s holiday, provided they were given an extra allowance of 1s 7d a day. After the meeting, the FDMA Executive met with the men and recommended that they accept this proposal. However, in a ballot, most of the lodges turned the proposal down, insisting on taking their full week’s holiday as was their right.[61]

The issue was discussed again at a meeting of the FDMA Executive on Monday 21 July, chaired by William Ellway, who represented Norchard on the Executive Committee.[62] The Executive was aware of the discontent among his members about the hours they were being asked to work and the pressure they were under and so Williams issued this statement to the local papers:

The miners of the Forest of Dean are entitled to a holiday each year under the terms of their agreement with the owners.[63]

In addition, the men rejected another attempt by the local colliery owners to make it compulsory to work six afternoon shifts a week. Concerning this request, Williams said:

As far as the Forest of Dean is concerned, this meant that the workmen are being asked to work Saturday afternoon shifts. The workmen’s representatives submitted that a ballot on this subject had been taken last year and the workmen had rejected the proposal flatly. The experiment of working six shifts had been tried at Princess Royal Colliery and it proved a failure: in fact, production decreased. The workmen’s representatives, therefore, rejected the idea of six afternoon shifts.[64]

The FDMA had agreed to encourage more miners to work on Sunday night to prepare the faces so that there could be full production on the Monday morning shift. At Eastern United, where some miners were working on Sunday nights, the issue of the loss of a bonus for missing a shift came up again. The reason was that sometimes miners missed the shift because the bus conveying them to work did not turn up. As a result, on 25 July, members of the FDMA Executive met to discuss the issue and this was followed by a mass meeting of Eastern United workers at Soudley Camp, where Wallace Jones announced that:

If the bus does not run you will not lose that wretched attendance bonus.[65]

On the same day, members of the FDMA Executive, representatives of the owners of the main Forest of Dean collieries and representatives from Bristol and Somerset coalfields met in Gloucester with Andrew Duncan, the President of the Board of Trade, to discuss issues connected to production targets and the shortage of coal.

The FDMA representatives were Williams, Harry Morgan (finance officer), Wallace Jones (Eastern), Elton Reeks (Princess Royal), Ray Jones (New Fancy), Frank Mathews (Cannop), John Harper (Waterloo), William Ellway (Norchard) and Harry Hale and C Brain (District Representatives).[66] The issue under discussion was the acute shortage of coal and a strategy for increasing production.[67]

Duncan continued to press the FDMA Executive to persuade the men to give up their one-week holiday and work extra shifts. Williams made it clear the miners needed rest to improve productivity and on Wednesday 30 July, issued the following statement to the local papers:

There is undoubtedly a shortage of coal in the country. At the same time, the miners need a rest very badly. That is a plain fact. The miners of the Forest of Dean gave up the greater part of their holidays last year. This year they intend to take their full holiday. It should be clearly understood that Forest miners are entitled to a week’s holiday under the terms of an agreement with the colliery owners, so they are not taking something which does not belong to them. The public does not realise that many miners with large families go to work on a poor diet and this has been going on for a long time. From about Wednesday in each week until they get their rations many of the workmen go to the pit with plain bread, or with a sandwich made up of bread and lettuce. Mining is exceptionally arduous and this kind of food does not contain enough nourishment to sustain a collier at his work.[68]

Williams went on to compare the situation of miners with those of other workers who have canteen facilities, adding:

It is extremely annoying to hear miners criticised by those people, who notwithstanding the war, and rationing, are bloated from eating and drinking the best which can be got by them, merely because they have plenty of money to buy what the poor cannot buy. Some of them have not done a stroke of work since the war started.[69]

At a meeting on Thursday 31 July 1941, the owners still refused to come to an agreement with the FDMA Executive over holidays and insisted that it should be left for each colliery to decide if it was to remain open during the holiday week. Williams pointed out to the Dean Forest Mercury that the SWMF had obtained an agreement that the miners should take a week’s holiday and it would be difficult for the FDMA to recommend any other course of action as they were now part of the same district. He went on to issue an instruction to all his members to take a holiday except for those who were needed to maintain the pits.[70]

Total War

On 22 June 1941, Germany launched an invasion of the Soviet Union, opening the most extensive land theatre of war in history. On July 12 1941, the British government and the Soviet Union signed the Anglo-Soviet Agreement, which was a formal military alliance committing both countries to assist each other and not to make a separate peace with Germany. The CPGB changed its policy and now throws its weight behind the war effort. The invasion impacted miners immediately because it led to increasing demands by the government, trade union leaders and the CPGB to increase coal production and munitions in solidarity with Russia.

Since the Anglo-Soviet pact, the strength of the CPGB both locally and nationally was growing and its national membership was on the way to its peak of 50,000 at the end of the war. Its main strength was within the mining and engineering trade unions, especially in South Wales and Scotland.[71] Communist officials within the MFGB, such as Horner and Paynter, wielded considerable influence over their members in reducing industrial unrest and pushing for higher productivity.

At this time, a small number of miners in the Forest of Dean, including several members of the FDMA activists, were members of the CPGB. These included Harry Barton, Len Harris and Tim Ruck from Cinderford and Reuben James and George Everett from West Dean. Some Labour Party and FDMA members were sympathetic to the communists and organised joint meetings with CPGB, FDMA, SWMF and Labour Party speakers. These included Williams, Ray Jones, William Wilkins, David Organ, Richard Kear, William Ellway and Albert Brookes.

Soon after, on 31 July 1941, the FDMA Executive met and passed the following resolution and asked it to be passed on to the Soviet ambassador in London:

- The Forest of Dean miners wish to express their deep and sincere admiration for the Red Army and its colossal and magnificent fight against the ruthless Fascist marauders.

- The Red Army has performed imperishable deeds for the everlasting benefit of the world.

- The Forest of Dean miners extend to the Russian people their earnest sympathy and ask that you convey these sentiments to the government of the USSR.[72]

Meetings

The leaders of the MFGB toured the country and held public meetings on the issue of how to increase the production of coal for the war effort. In July, a series of meetings arranged by the Ministry of Information were held across the Forest of Dean.

Two meetings were held on Sunday 27 July; the first at the Barn, Cinderford, chaired by William Ellway and the second at the Camp, Soudley, chaired by Wallace Jones. The speakers were Will Paynter from SWMF Executive and a CPGB member, Charles Gill, the miners’ agent for Bristol, E J Plaisted from Bristol City Council, an ex-South Wales miner who was blacklisted after 1926 and Williams.[73]

Paynter reported that out of 100,000 ex-miners who had been required to register on Bevin’s programme, 25,000 men had volunteered to return to the pits. He warned of the dangers of fascism, the dire situation facing Russia and the need to make an extra effort to increase coal production. Paynter spoke of his own experiences as a miner in South Wales and his involvement in the fight against fascism as a volunteer during the Spanish Civil War. The Gloucester Citizen reported Paynter arguing that:

while they all realised that miners had suffered injustices in the past and were suffering injustices today, they should not do anything to the detriment of the effort that would mean the destruction of Hitler and all he stood for.[74]

Williams said he recognised the importance of coal for the war effort but spoke up in defence of his members. He argued that the miners in the Forest of Dean were working at their maximum potential and could not produce more coal without extra manpower. He suggested returning men from the military to the pits, better organisation in the pits and nationalising the mines. He added that only 100 out of about 200 ex-miners from the Forest working in other industries had returned to the pits.[75]

Pay and Conditions

The issue of the attendance bonus had been causing problems in other districts and as a result, on 4 September 1941, the MFGB obtained an agreement with the owners that the condition of full attendance attached to the bonus would be dispensed with. However, the MFGB accepted a provision that the production committees ensure that measures are taken against any individual whose conduct mitigates against the maximum production of coal.[76]

On Monday 6 October, the FDMA Executive met with the colliery owners to discuss pay and conditions. Williams told the Dean Forest Mercury that under pressure, the owners had conceded a district pay rise to the lower-paid men, including trammers, drivers, fillers, train attendants, conveyor loaders and landers, horse drivers and bond riders. The increase was from 4s 10.5d per shift to 5s 3d per shift.

The FDMA Executive also achieved an agreement with the employers that a dispute committee be set up, made up of two workers and two employer representatives. In addition, the FDMA obtained an agreement for an increase in rates for injured workmen. The Executive put in a claim for an increase in holiday pay, but the owners decided to defer the matter to give their decision later. [77] In the last quarter of 1941, all miners were receiving a cost-of-living addition of 2s 8d plus the attendance bonus of 1s above the minimum rates in the district agreements.[78]

Canteens and Baths

The FDMA had been campaigning for the installation of pit head baths and canteens for many years, arguing that this would take the pressure off the work done by miners’ wives. However, the issue of pit head baths and adequate food for miners had been rumbling on for a while. Cannop was the only colliery that provided a canteen and pit head baths. In July 1942, the miners discovered they had an ally in the local GP, Dr W H Tandy, who had raised the matter of the quality of food available to the miners in the columns of the Dean Forest Mercury.[79]

The matter was taken up by Philips Price who raised the subject with the Ministry of Food who informed him that they were in the process of consulting with the Ministry of Mines about proposals to install canteens and pit head baths across the coalfields with finance from the Miners’ Welfare Fund.[80] Consequently, the Ministry of Supply and the Ministry of Food negotiated an agreement with the Forest of Dean colliery owners to provide canteens at all the main collieries with funding for the buildings and equipment from the Miners’ Welfare Committee. The plan was that miners would be provided with nutritious food such as meat sandwiches, pasties and pork pies supplied by the Ministry of Food, although it would take some years before it was fully implemented.[81]

Princess Royal was the second pit in the Forest to build pit head baths and the opening ceremony was planned for Saturday 20 September 1941. However, in early September, a dispute arose between the FDMA and the baths committee of the colliery over the terms and conditions of employment of the two bath attendants. The attendants had asked the Princess Royal pit committee and the FDMA to intervene on their behalf to negotiate trade union terms and conditions. However, the baths committee refused to meet with the pit committee and then employed two other attendants in the place of the original two workers whose offer of employment was cancelled.[82] On 18 September 1941, Williams issued a statement outlining the history of the case and ended it as follows:

The Miners’ Executive requests all members to refrain from attending the opening of the Baths as a protest the refusal of the Baths Committee to meet the Union representatives.[83]

A picket was placed across the gate of the pit on the day of the opening ceremony. As a result, the event was only attended by representatives of the colliery owners and other Forest dignitaries with only a handful of miners.[84] On 29 February 1943, a canteen was opened at Northern United and the FDMA continued to campaign for pithead baths and canteens at all the collieries.

William Jenkins

In the Autumn, FDMA member William Jenkins, who worked at Cannop, was appointed by the government to the full-time post of Labour Supply Inspector for the mining industry in the Forest of Dean. His job involved liaising between the Department of Employment and the collieries to ensure the efficient use and distribution of labour. His principal duties were to examine demands for skilled labour, including training and the redistribution of miners within the coalfield.

Deakin was still having problems recruiting and maintaining the workforce at New Fancy and absenteeism was higher than in the other pits.[85] In November, a dispute arose over a proposal to transfer fifty men from Cannop to other Forest collieries, including twenty men to New Fancy. Unfortunately, this was arranged between William Jenkins and O.G. Oakley, the manager of Cannop, without consulting the workmen’s representatives on the District Coal Production Committee. Williams was furious and released a statement to the press, which said:

It is the function of the District Coal Production Committee to make allocations of workmen to the collieries in this district which need the men most. Therefore, I at once made a protest to the Committee on behalf of the workmen that a fait accompli had been presented and that before anything was done on this matter it should have been brought before the local Coal Production Committee. I warned the Committee that this action would cause considerable resentment among the workmen and this view was echoed by the whole of the workmen’s side of the Production Committee.[86]

Williams said that this had caused considerable unrest and there would be a mass meeting on Sunday to discuss the matter. The issue brought to the surface the feeling among miners that their knowledge and experience of the local industry were being ignored and there was little consultation over production policy. The authorities still refused to entertain the idea that the drop in productivity was due to the loss of skilled miners from the industry and continued to blame the shortage of coal on the miners and absenteeism.

In December, the authorities gave the pit production committees the authority to report any miner who was absent from work without just cause to the National Service Officer, who had the power to prosecute or conscript the men into the military. However, this task was intensely disliked by the miners’ representatives on the committees, who claimed they would prefer to spend their time dealing with issues of production.[87]

Prosecutions

In the three months ending 6 November 1941, about twenty thousand ex-miners had returned to British pits. As the winter approached, the authorities made further attempts to track down ex-miners, some of whom had left the industry years ago due to unemployment, poor conditions and low pay. If they were found, the Department of Labour sent them letters requesting them to report to a particular colliery, sometimes with only a few days’ notice.

Some of these men had health problems and were reluctant to transfer back to an industry with hazardous and unhealthy work conditions. There was the added problems of a possible wage cut and having to move home. One man in the Forest of Dean complained: “I don’t even have any pit boots!”[88] Not surprisingly, some men refused to comply and so were brought before the courts.

In one case before the Coleford Police Court, William Jones (33) from Coleford, failed to comply with a direction given by the Ministry for Labour to return to work at Princess Royal Colliery. Jones worked as an aircraft fitter and left Cannop colliery in 1937 because of ill health and irregular employment. He had applied to join the RAF but was turned down due to his medical condition. He had registered with the Department of Labour as an ex-collier as required but on the advice of his employer, had ignored the instruction to return to Princess Royal. The court decided there were mitigating circumstances and his case would be referred to the Ministry of Labour.[89]

In another case, George Chamberlain (31) of Cinderford was directed by the Ministry of Labour to return to work at New Fancy Colliery. Chamberlain had ten years of experience as a collier. When he was asked to justify his failure to comply, he could not make himself understood because his speech impediment was so bad. His representative from the Transport and General Workers Union explained that his client had a deep fear of the pit owing to the early death of his father from lung disease. The magistrates directed that Chamberlain should immediately start work at New Fancy.[90]

| On 30 December 1941, Lewis Simmonds was killed at Waterloo Colliery |

Discontent

During the winters of 1941 and 1942, the danger of severe coal shortages became acute, and the gap between estimated consumption and estimated production widened. The EWO had not provided enough extra manpower, and discontent rumbled through the coalfields over the conditions in the pits and the pressure on miners to increase productivity.

On 9 January 1942, miners at Betteshanger Colliery in Kent struck over allowances for working difficult seams. The Ministry of Labour decided to prosecute 1,050 miners for contravening the Emergency Powers Act. Three local union officials were imprisoned, some of the strikers were fined £3 each and a thousand other miners were fined £1 each. The Betteshanger miners continued their strike and other Kent pits came out in sympathy. On 28 January, the managers gave in to their demands and in February, the Home Secretary dropped the prison sentences. By May, only 9 miners had paid their fines, and, in the end, most fines were never paid. Kent was not alone and in the first three weeks of May 1942, there were eighty-six unofficial strikes across the British coalfields involving 58,000 men.[91]

| On 24 January 1942, William Thomas, age 35, was killed at Eastern United colliery |

Threat of Industrial Action

In January 1942, Williams had to deal with the threat of industrial action at Eastern United. The dispute had its roots in the butty system, which was abolished in 1938. An account of how the butty system worked in the Forest of Dean is provided on this website under the section on articles.[92] In cases of teams working on piecework, it was still normal for one person to be responsible for the place of work and to collect a joint wage packet for the team to share on an equitable basis. The problem was that it was unclear how much money any individual was being paid or whether the butty system had continued in some form or another, with the money not being shared equally.[93]

In addition, this arrangement caused problems with income tax since there was no record of actual earnings by any individual miner working in the hewing team. Consequently, some members of the team may have been paying more or less tax than they should. Also, injury compensation was based on earnings and if the company had no record of actual earnings, then the benefit would be difficult to calculate.

As a result, on 31 December 1941, in response to requests from its members mainly in the West Dean pits, the FDMA presented a proposal to the colliery owners that in future all the workmen should be given a separate wage packet setting out their earnings and deductions individually. The owners agreed, but on the condition that the extra clerical work would mean payday being put back by two days. On 16 January 1942, some men at Northern United and Eastern complained about the new arrangement and at Eastern, this led to a threat of strike action. Williams was appalled and issued a statement which included the following text:

Fellow Workmen. For some time now an agitation has been on foot among you and there has been some talk of going on strike, and a lot of talk about taking a ballot on the settlement reached between the coal owners and the Miners’ Executive on the miners’ demand that each workman should be given a separate pay packet. I am ashamed that there are miners to be found who are so short-sighted, and in some cases so mean, as to associate themselves with this stupid agitation.[94]

The increasing authority of the FDMA meant that Williams was able to prevent an unnecessary strike and from now on all the workmen would receive individual wage packets. In addition, in February 1942, Williams negotiated an agreement with the owners that all miners would now be required to become members of the FDMA.

Deakin

Meanwhile, the threat of closure still loomed over New Fancy colliery and it was anticipated that the men would be given notice of termination of their employment on Saturday 14 March 1942. Deakin announced that the pit was still short of about forty men and the problems of absenteeism had continued. He said it was necessary to produce about 220 tons of coal a day to maintain profitability and now it was only producing about 160 tons a day. Williams responded:

During the past month, there had been a considerable amount of illness and furthermore, some of the men had been working seven and eight shifts a week and probably finding themselves unable to keep it up had a day’s rest; that sent up the percentage. We shall do everything that lies within our power to keep the pit open.[95]

Ray Jones, the FDMA Executive member for the New Fancy, produced a report on the situation at the pit. Williams used this information to make a case for keeping the pit open to the SWMF and the Mines Department. Consequently, on 12 March, Deakin announced that he would keep the pit open for the time being.

Government Control