Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History reserve the copyright of this article but give permission for parts to be reproduced or published provided Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History are credited in full.

Introduction

“Machine with the strength of a hundred menCan’t feed and clothe my children.”

Lisa O’ Neill from her song Rock the Machine from her album Heard a Long Gone Song

“The level always has the command of the mine, waterworks (whether engine or otherwise we call waterworks) we do not think anything of, but the level is what commands the mine. A level is the mother of a mine.”

Free Miner, Thomas Davies (1832)

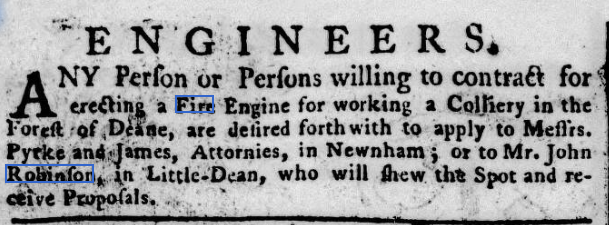

On 4 June 1774, some person or persons attempted to destroy the Fire Engine colliery at Nailbridge near Cinderford in the Forest of Dean. One of the owners of the colliery was John Robinson, who, at the time, worked as a representative of the Crown in the Forest of Dean. The following report appeared in the Gloucester Journal on 13 June 1774.

WHEREAS some Time in the Night of Saturday last, the 4th Instant, some Person or Persons feloniously entered the Engine-House belonging to the Fire- Engine near Nailbridge in the said Forest, and maliciously threw a large Quantity of Stones, Rubbish, and two Iron Bars, into the Snides of the said Engine, with Intent to injure and totally prevent the Working thereof:

This is to give Notice, That if any Person or Persons will give Information upon Oath against the Offender or Offenders, so as he, she, or they may be convicted thereof, the Person or Persons giving such Information shall receive a Reward of TWENTY GUINEAS of Mr. John Robinson, of Little-Dean; an Accomplice giving such Information shall receive the Reward and be pardoned.

NB. By Statute 9 of Geo. II. it is enacted, “That if any Person or Persons shall wilfully or maliciously set fire to, burn, demolish, pull down, or otherwise destroy or damage, any Fire-Engine, or other Engine for draining Water from Coal-Mines, or for drawing Coals out of the same, or any Bridge, Waggon-Way, or Trunk for conveying Coals, or Staith for depositing the same, every such Person, being lawfully convicted of any or either of the said several Of- fences, or of causing or procuring the same to be done, shall he adjudged guilty of Felony, and subject to the like Pains and Penalties as in Cases of Felony.”

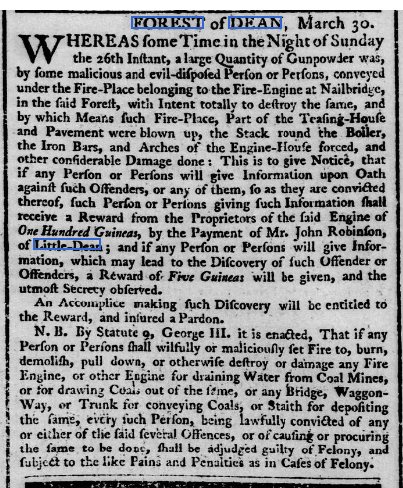

Another attempt to destroy the Fire Engine was made a year later. On 26 March 1775, some person or persons attempted to blow up the Fire Engine colliery at Nailbridge near Cinderford in the Forest of Dean using gunpowder. The following report appeared in the Gloucester Journal on 3 April 1775.

Sometime in the night of Sunday the 26th, a large quantity of gunpowder was, by some malicious or evil-disposed person or persons, conveyed under the fireplace belonging to the Fire Engine at Nailbridge, in the said Forest, with intent totally to destroy the same, and by which means such fireplace, part of the teasing house and pavement were blown up, the stack round the boiler, the iron bars, and arches of the engine house forced, and other considerable damage done.

This is to give notice, that if any person or persons will give Information upon oath against such offenders, or any of them, so as they are convicted thereof, such person or persons giving such information shall receive a reward from the proprietors of the said Engine of One Hundred Guineas, by the payment of Mr. John Robinson, of Littledean; and if any person or persons will give Information, which may lead to the discovery of such offender or offenders, a reward of Five Guineas will be given, and the utmost secrecy observed.

An Accomplice making such a discovery will be entitled to the Reward and insured a Pardon.

NB. By Statute 9, George 111, it is enacted, that if any person or persons shall wilfully or maliciously set fire to, burn, demolish, pull down, or otherwise destroy or damage any Fire Engine, or other engine fur draining water from coal mines, or for drawing coal out of the same, or any bridge, waggon way, or trunk for conveying coals, or staith for depositing the same, every such person, being lawfully convicted of any or either of the said several offences, or of causing or procuring the same to be done, shall be judged guilty of felony, and subject to the like pains and penalties as in cases of felony.

No record of anyone claiming the award or being prosecuted for the offences exists.

BACKGROUND

Most of what follows will draw on the research of Chris Fisher (see Custom, Work and Market Capitalism, The Forest of Dean Colliers, 1788-1888, London: Breviary, 2016 and The Forest of Dean Miners’ Riot of 1831, Bristol: BRHG, 2020) and the research of Cyril Hart (see The Free Miners of the Royal Forest of Dean and Hundred of St Briavels, Lydney: Lightmoor, 2002). Fisher or Hart do not mention the blowing up of the Fire Engine Pit in 1775 but their texts provide an insight into the motives behind the attack on the mine. The use of the word ‘foreigner’ in this text generally refers to capitalists from outside the Forest of Dean.

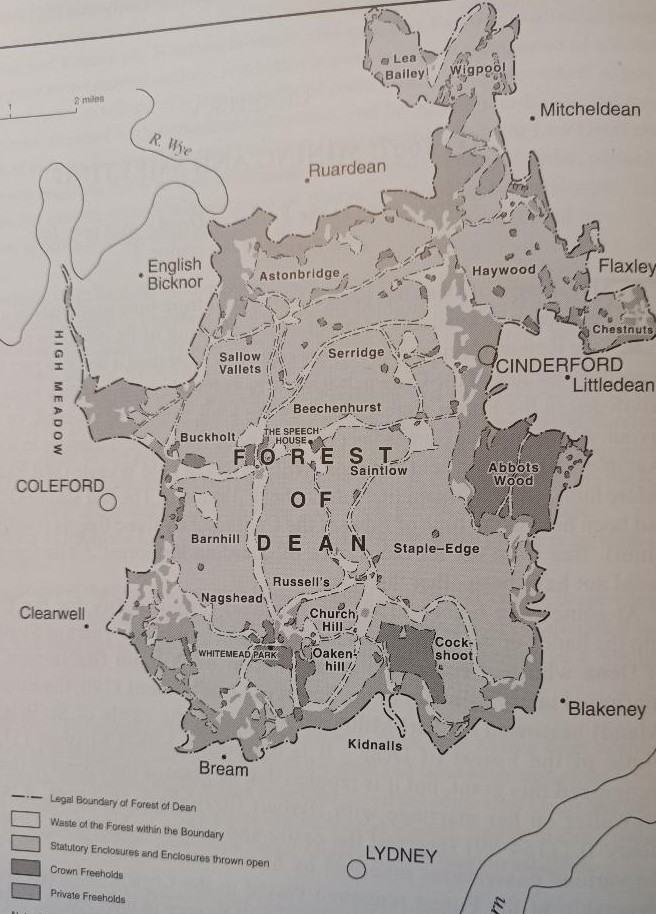

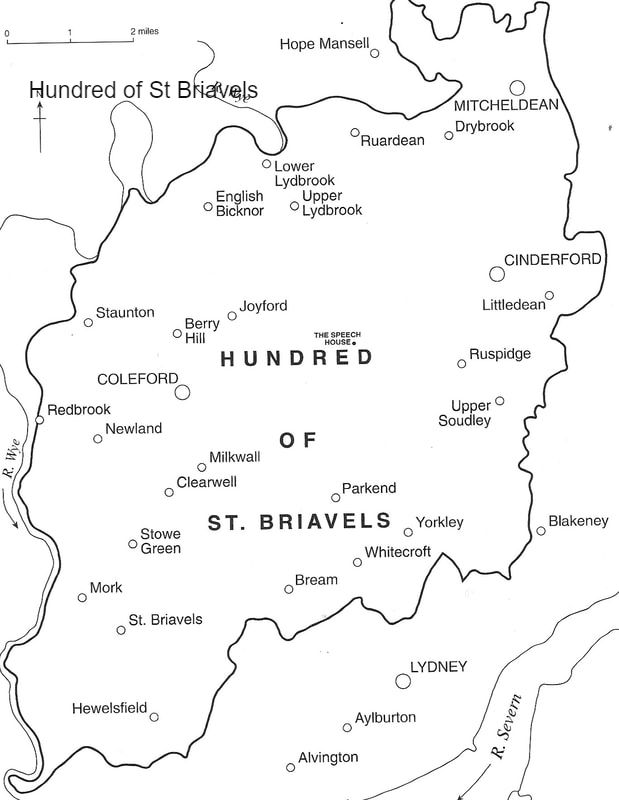

The statutory Forest of Dean and the minerals below it were and still are owned by the Crown. At the time of the explosion, Foresters claimed that free mining rights had been held ‘tyme out of mynde’. These allowed any son of a Free Miner who had worked a year and a day in a mine and was born within the Hundred of St Briavels to open a pit anywhere in the statutory Forest of Dean by registering the right to mine a gale with the Deputy Gaveller. A gale was a grant to a small section of a specific seam of coal or deposit of iron ore or stone in a defined location. The Deputy Gavellers worked for the Crown and were responsible for registering the mines, seeing that the customary modes of working were enforced and collecting royalties.

Book of Dennis

The first formal statements of these rights can be found in 1687 in “Laws and Customs of the Miners in the Forrest of Dean“, which was the result of an Inquisition by forty-eight Free Miners at some time before 1610 when they wrote down all that was remembered about their customary rights. This was what the miners called their “Book of Dennis”.[1]

In return for their rights and privileges, the miners had to pay a royalty on the tonnage raised to the Crown through the Deputy Gaveller. The Book of Dennis also prescribed the distances between mines, the size of containers to carry the coal, and the procedures to be followed when workings met underground. In addition, miners were allowed to build roads for the carriage of coal from the mine to the nearest Crown’s highway and to take timber from the Forest for use in the mines, without cost. Clause 24 in the Book of Dennis states that:

Alsoe every miner in his last dayes and at all tymes may bequeath and give his dole (share) of the mine to whom hee will as his own chatel, And if hee doe not the dole shall descend to his heirs.[2]

This clause is ambiguous and was later interpreted by some Free Miners to mean that they could sell a coal holding to a foreigner. However, Clause 30 of the Book of Dennis seems to exclude foreigners from the mines:

Alsoe no stranger of what degree soever hee bee but only that beene borne and abideing within the Castle of St Brievills and the bounds of the fforest, is as is aforesaid, shall come within the Mine to see and knowe ye privities of our Sou’aigne Lord the King in his said Mine.[3]

Again, there was some ambiguity in this. Certainly, foreigners were excluded by Clause 30 from entering the mines and, therefore from working in them and becoming Free Miners. It does not, however, specifically prohibit foreigners from participating in the industry as non-working partners.

Mine Law Court

In most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the customary right to mine was regulated by the Mine Law Court, which operated in the manner set out by the Book of Dennis. The Court dealt with disputes, enabled a democratic and fair system of self-regulation, limited the accumulation of wealth by a single individual, and set out to ban outsiders from entering the industry.

All disputes among the miners were tried before the Mine Law Court, presided over by the Constable, usually a local nobleman based at St Briavels Castle, the Castle Clerk, and the Deputy Gavellers.[4] Matters were judged, with no foreigners present, by juries of twelve, twenty-four or forty-eight Free Miners whose decisions were final and binding. In addition, the Court could make further laws and regulations for the regulation of the industry. Miners were encouraged to hold to the Court and to enforce its decisions by a regulation which awarded to the plaintiffs half of any fine imposed on any other miner they successfully sued for breach of custom.

The Court established the size of the measures to be used in selling and carrying the coal and set the prices to be charged to different customers in different places. To ensure that the miners set their prices in accordance with this scale, the Court sometimes appointed panels of ‘Bargainers’ whose job was to arrange prices with regional or industrial groups of customers. Only Free Miners were allowed to transport coal (usually to the River Severn or Wye) and they were required to sell at the price fixed by the Bargainers. To defend its regulations and jurisdiction, the Court, from time to time, collected levies on all miners and coal carriers to provide funds for legal expenses.

The Court’s primary function was to limit entry to the industry. Only the sons of Free Miners who had been born in the Hundred of St Briavels and who had served an apprenticeship of a year and a day with their fathers or other Free Miners were permitted to become Free Miners. The sons of fathers not born free had to serve an apprenticeship of seven years if they wished to gain their freedom. The Court further guarded against the intrusion of outsiders and the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few men by stipulating that only Free Miners should carry the coal to market and that no carrier should have more than four horses for his business.[5]

The only exception allowed to these rules was that the Court might create honorary Free Miners who were entitled to the usual franchises and privileges. This occurred at times when the miners felt they needed the support of influential people. However, this was a breach of the Clauses in the Book of Dennis and, as we shall see, sowed seeds of discord at the end of the eighteenth century.

The Governor and Company of Copper Mines in England

There was no ambiguity about the Mine Law Court’s intention to closely limit the industry to native miners. In the early 1750s, The Governor and Company of Copper Mines in England had enclosed land for their own mining and had attempted to exclude local miners from it. They had obtained the gale from free miners who had either sold it or given it to them.[6] In 1832, during the proceedings of a Commission appointed by the government to investigate mining in the Forest, William Collins, aged 77, deposed:

The miners tried to stop the company and could only do it by cutting under and letting the company’s work fall in.[7]

In other words, the mine was destroyed by miners tunnelling underneath it and causing its collapse. In 1752, the Company sued a party of miners for damages in the Court of the King’s Bench but their action failed when the jury found in favour of the miners, who pleaded the customary right to mine wherever they wished. So, at this time, any large-scale, systematic attempt by foreigners to open mines in the Forest was vulnerable to undermining, against which they appeared to have no remedy at law.

Coal Mining

The miners worked in ‘companies’ where each ‘vern’ or partner had an agreed ‘dole’ or share of the profit. One of them acted as the leader of the company:

the strict custom required that the mines should be worked by companies of four persons, called verns or partners, the King considered as a fifth … [8]

Under this system, the ownership of the mines was spread among a fairly large number of men and was not concentrated in the hands of a few.

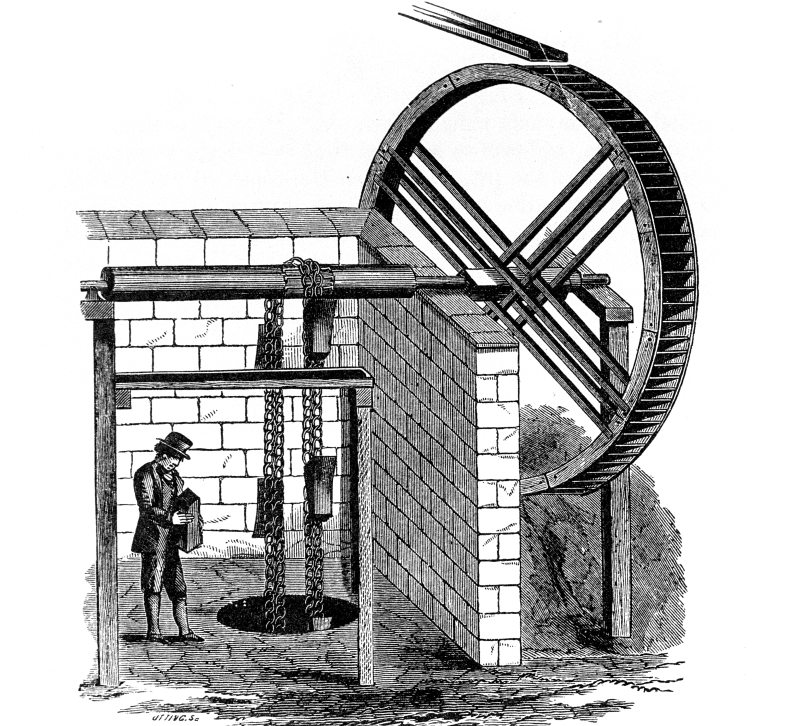

The industry that worked within this customary framework was made up of relatively shallow pits and levels that worked the outcrop of the seams in the Forest coal basin, and these were limited in extent by the difficulty of dealing with water in the coal. Where they could, the miners took advantage of the slope of the seams to help with drainage. However, Rev H.G. Nicholls wrote in that:

If the vein of coal proposed to be worked did not admit of being reached by a level, then a pit was sunk to it, although rarely to a greater depth than 25 yards, the water being raised in buckets, or by a water wheel engine, or else by a drain having its outlet in some distant but lower spot … the chief difficulty being found in keeping the workings free from water, which in wet seasons not infrequently gained the mastery and drowned the men out.[9]

However, up to the end of the eighteenth century, most of the Free Miners were hostile to the use of deep pits with water wheels to pump water because of the cost. The culture was one of small-scale cooperative working of levels to access the coal and this was reflected in the detailed regulations of the Mine Law Court.

Deep pits could also interfere with the workings of nearby levels which were driven at a near horizontal level into the ground. The discharge of large quantities of water on the surface by water wheels could impact the workings or flood nearby levels.

On the other hand, the pumping of water to the surface could benefit nearby mines, which were in danger of flooding, by lowering the water levels in their workings. However, in 1832, during the proceedings of the 1831 Commission, Free Miner, Thomas Davies, argued that:

The level always has the command of the mine, waterworks (whether engine or otherwise we call waterworks) we do not think anything of, but the level is what commands the mine. A level is the mother of a mine.

As a result of this long-standing custom, the Mine Law Court made certain regulations around the use of water wheel engines. In 1754, after the introduction of a water wheel engine at the Oiling Green colliery, the Court ordained that:

No free miner or miners shall or may sink any water pit and get coal out of it Above and Beneath the Wood within the limits or bounds of one thousand yards of any freeminer’s level to prejudice that level; if they do they shall forfeit the penalty of the Order which is £5, one half, etc.[10]

This was because levels could be several hundred yards long before they met a seam of coal. In the case of pits, the Mine Law Court regulations stated that they only had a protection of 12 yards from the centre of the pit. This had the effect of restricting the use of pits. In 1832, during proceedings of the Commission, Thomas Davies said that:

`the bound is 1,000 yards. If the gaveller gives a gale within 800 yards, the galee has a right to cut off any water pit, if he has a level that will raise the coal.[11]

In making the 1,000 yard regulation in 1754, a reference in the Mine Court Law documents is made to the Water Wheel Ingine at the Oiling Green near Broadmoor. This was the first time a Water Wheel Engine was established in the Forest.[12] The document reveals that its owners had been influential enough to successfully get the pit categorised as a level to circumvent the regulations.

Fire Engines

Steam engines (often called Fire Engines) could help to overcome the problem of pumping water from mines more effectively than water wheels. These engines were usually based on an invention by Thomas Newcomen in 1708 of a self-acting atmospheric engine. They were expensive to buy and required a lot of coal to run. They became quite popular in the coal industry and by the end of the eighteenth century were mainly used to pump water out of pits.

However, up to the end of the eighteenth century in the Forest of Dean, most mines were levels or shallow pits of the type described by Rudder in 1799:

were not deep – because when the miners find themselves much incommoded with water, they sink a new one, rather than erect a fire engine, which might well answer the expense very well.[13]

Most Free Miners did not have the capital necessary for their installation, and the custom generally excluded foreigners who could supply the capital. However, it appears that by 1775, John Robinson and his son Thomas Robinson (Snr), in conjunction with a group of foreigners, had bought a mine from free miners and established the first steam engine or “fire engine” to pump water in a mine in the Forest. The mine was The Fire Engine (originally The Oiling Gin or Water Wheel at the Orling Green near Broadmoor).

The company of gentlemen included John Robinson of Little Dean; Robert Pyrke of Newnham; Selwyn Jones of Chepstow; Thomas Weaver of Gloucester; Joseph Lloyd of Gun’s Mills; Thomas Crawley Boevey, of Flaxley, Esq. The company also included a free miner called William Howell of Littledean, in whose name the gale was now registered. Howell retained sixteenth of the shares in the company.

John Robinson (1712-1784) was Deputy Gaveller from at least 1775 to 1777 and his son Philip Robinson (1744-1809) also later held the position. Robert Pyrke was a shipping entrepreneur and merchant who built a new quay at Newnham in 1755 with cranes and warehouses. Thomas Weaver was a pin manufacturer from Gloucester. Joseph Lloyd was a businessman who converted Gunns Mill into a paper mill. Thomas Crawley was an aristocrat who inherited Flaxley Abbey in 1726. It is unlikely any of these men had ever worked in a mine but they had the wealth and capital to fund a fire engine and probably employed others to do the work for them on piece rates or wages.

Some free miners would not have been happy with the intrusion of foreigners into their industry, even if they were honorary free miners or Crown officials. Also, a fire engine would have been far more efficient at pumping water than a water wheel and so there may have been conflict over the discharge of large quantities of water impacting nearby levels.

Last Meeting of the Court

A meeting of the Mine Law Court held in August 1775 agreed that the sale of mines to foreigners was not acceptable to the Court and that the Court should have some jurisdiction over these sales, although there was still some ambiguity.

Clause 8: Every miner or collier may give his mine or coal works to any person that he will, but if he does give it by will, that person, if required, shall bring the testament, and show it to the Court, but if it is a verbal will, he shall bring two witnesses to testify the will of the miner.

Clause 16: Foreigners having any mine or coal work carried in the Hundred of St Briavels, shall sell it to some free miner by private contract if they can, or otherwise expose it to sale by auction, by the Mine Law Court.

Clause 17: If a free miner dies and leaves his mine or coal works by will or testament to a foreigner, or it comes to him by heirship or marriage, he shall sell it as aforesaid, or hire Free Miners to work for him.

Clause 18: If any free miner sells any mine or coal work to a foreigner, he shall be liable to a penalty of £20, to be recovered in the Mine Law Court.[14]

The need for this restatement indicates that there was tension between miners and foreigners. The foreigners, including certain Crown officers, Deputy Constables, and Deputy Gavellers, had at one point been granted honorary Free Miner status, likely in recognition of services rendered to the miners. Some of these honorary Free Miners had gone on to acquire other mines as well as the Fire Engine. These were the Brown’s Green and Gentlemen Colliers. In each case, they had taken foreigners into partnership. This arrangement appears to have been a key factor behind the resolutions of 1775 listed above.

In 1772, in the period of John Robinson’s tenure as deputy gaveller, the rent for Brown’s Green colliery was paid for by Partridge, Platt and Co., who were foreigners even though the names in the gale book for the gale were different.[15] In 1792, the name on the gale book was George Morse, who was probably a Free Miner.[16] Thirty years later, the name of the mine had changed to the Lidbrook Water Engine and the names on the gale book were Harford, Partridge and Co. This company owned forges and traded in iron and its products in Bristol and Monmouth.

In 1766, the Gentlemen Colliers was owned, at this time, by a company of ‘gentlemen’ from Coleford, all or some of whom were honorary free miners from Coleford and Newland.[17] In 1766, the gale was held in the names of the following: Mr Richard Sladen, Mr Dew, Richard Wilcox, Mr Dutton, John Hawkins, John Sladen, Henry Wilcox and Henry Yarworth. Richard Sladen owned the Inn, The Plume of Feathers, in Coleford, and some of the others were local tradesmen and/or property owners.

Theft

The court’s records, usually kept at the Speech House, were targeted after the court’s session in August 1775 when someone broke into the chest where these documents were stored and removed them. This was the last time the court sat and this left the supervision of mining customs solely in the hands of the Deputy Gaveller, John Robinson. Fifty-three years later, Thomas Davis, a free miner aged eighty, said in evidence before the Dean Forest Commissioners, who were inquiring into the miners’ rights, that:

The Mine Law Court was given up, because of a dispute between Free Miners and foreigners, whom we did not consider fit to carry on the works. I believe the Court was given up because somebody took all the papers away from the speech house, and they were considered to be stolen. The Gaveller, one John Robinson, was a partner in the Fire Engine and was supposed on that account to have taken them away.[18]

A memorial presented to the Commissioners by Mr Clarke on behalf of the Free Miners echoed a similar sentiment, though it did not explicitly name Robinson.

Foreigners, unable to bypass the barriers imposed by the Mine Law Courts—particularly the 1775 orders that prohibited them from working in the mines—recognised that their only chance for success lay in ridding the Forest of the Mine Law Court altogether.

Two of the partners in the Fire Engine were John and Phillip Robinson Snr, father and son, and both Deputy Gavellers. One of them was also a Clerk to the Mine Law Court and had possession of the records. The inference which all this suggests is that John Robinson had stolen the records and then, in his capacity as Deputy Gaveller, had refused to hold the Court again because there were no records. The records reappeared in 1832 in the hands of Phillip Robinson Jnr (1784- 1857), son of Phillip Robinson Snr, and assistant to the Deputy Gaveller. In 1832, Philip Robinson Jnr recalled:

I have heard my father often converse with Free Miners, and tell them it was their own fault the Mine Law Court dropped, and arose from their own supineness.[19]

Conclusion

The role of the Robinsons in the theft of the Mine Law court records is subject to doubt as the evidence is only circumstantial. However, the cessation of the Court had no important immediate consequences. The three mines, Fire Engine, Brown’s Green and Gentlemen Colliers, in which foreigners had a share, were a small minority of the total number of mines. In 1776, it appears that the Fire Engine passed back into the hands of four Free Miners (Thomas Hale, James Tingle, Anthony Mountjoy and Thomas Hobbs) for the sum of £2200.

The cases of these three mines, all of which involved Crown officers, were the only substantial intrusion by foreigners into the Forest of Dean coalfield before about 1800. The destruction of the Fire Engine appeared to have curtailed any attempt to challenge long-established customary rights of Foresters to mine coal in the Forest of Dean. This was not an act of vandalism but a serious and successful attempt to defend a community from powerful social and economic forces which challenged their way of life.

This did not last. The Free Miners petitioned for the revival of the Mine Law Court but were ignored. This failure created an environment in which the strict rules governing ownership of the mines began to break down. Some free miners took advantage of this, in particular the Teague brothers, George, James and Thomas.

By 1788, free miners George Teague and George Martin (who was also a farmer) had installed a fire engine at their pit, the Nofold Fire Engine Colliery near Cinderford.[20] In 1795, a free miner, James Teague, who had formed partnerships with foreigners, installed a fire engine and sunk a pit on his Potlid Gale about a mile north of Broadwell.[21]

As time went on, more Free Miners broke ranks and sold their pits or went into partnership with outside industrialists. This was a major factor in allowing capitalists to move into the Forest in the early nineteenth century and to start opening bigger and deeper coal mines.

As a result, the early nineteenth century saw the penetration and transformation of the old free-mining coal industry by capitalists from beyond the borders of the Forest. In the years between 1790 and 1830, the mining industry in the Forest of Dean passed, in the main, from the hands of a relatively large group of working proprietors of small-scale co-operative pits into those of a small group of men, mostly outside capitalists, who brought with them the steam engine, deep mining, tram roads and iron furnaces.

The owners of the tram roads charged high toll fees, which were often unaffordable for some of the smaller Free Miners who were no longer able to claim the sole right to transport coal. [22]In addition, from about 1810, the Crown decided to enclose large areas of the Forest for timber production for the Royal Navy. Not only did this prevent miners from accessing Forest land to mine its minerals, but it also limited their customary right to run animals in the woods.

By 1830, Edward Protheroe, from Bristol, had become the most powerful capitalist in the Forest. He had invested the money he made from the slave trade and from his West Indies plantations into thirty coal pits as well as iron mines and iron works. He employed about 500 men and owned substantial shares in the new tram roads. In 1831, Protheroes told the Commissioners:

The depth of my principal pits at Parkend and Bilson varies from about 150 to 200 yards; that of my new gales for which I have engine-licences, is estimated at from 250 to 300 yards. I have 12 steam-engines, varying from 12 to 140hp, nine or ten of which are at work, the whole amounting to 500hp; and I have licences for four more engines, two of which must be of very great power.[23]

The ability of approximately one thousand Free Miners, operating small levels to access the outcrop of coal, to compete with men like Protheroe was curtailed and, as a result, most of the inhabitants of the Forest were now dependent on the wages they earned working in the new deep pits owned by the capitalists. Many were reduced to poverty and some to unemployment. In 1831, the people of the Forest of Dean rioted, tore down the enclosure fences and attacked the property of Protheroe’s agent. But that is another story.[24]

Lisa O’ Neill, Rock the Machine, from her album Heard a Long Gone Song

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTDjWZ1VOm4

[1] A copy of The Laws and Customs of the Miners in the Forest of Dean is held in the Gloucestershire Archives. Cyril Hart has reprinted in its entirety in his The Free Miners. Clause numbers given here correspond to Hart’s paragraph numbers.

[2] Hart, The Free Miners, 39.

[3] Hart, The Free Miners, 40.

[4] The Constable was the King’s man, responsible for mediating between him and his subjects in the Forest on all matters other than those concerning the timber. Through the Gavellers and Deputy Gavellers and the Mine Law Court, he supervised the mining industry and saw that the King had his share of profit from it. He also conducted a court which adjudicated claims of debt among the foresters and maintained a debtor’s prison at the St Briavels Castle. The Marquis of Worcester, the Duke of Beaufort and the Earl of Berkeley acted as Constables from time to time during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries

[5] Hart, Free Miners, 73-74.

[6] Hart, The Free Miners, 272

[7] Ibid.

[8] Fisher, 1831 Riot, 41.

[9] H.G. Nicholls, The Forest of Dean, 2nd edition, edited by C.N. Hart, (Whitstable: David and Charles, 1966), 238 – 239.

[10] Hart, The Free Miners, 125 – 126.

[11] Hart, The Free Miners, 302.

[12] Hart, The Free Miners, 126 and 139.

[13] Rudder, S. quoted by Nicholls, The Forest of Dean, 237.

[14] Hart, The Free Miners, 126-127.

[15] Hart, The Free Miners, 271.

[16] Hart, The Free Miners, 266.

[17] Hart, The Free Miners, 258.

[18] Fisher, The 1831 Riot, 38

[19] Hart, The Free Miners, 270.

[20] Ralph Anstis, The Industrial Teagues of the Forest of Dean (Gloucester: Alan Sutton) Chapter Four.

[21] Anstis, The Industrial Teagues of the Forest of Dean 23-24.

[22] Tram roads were made using iron rails fitted to stone blocks to allow horse-drawn wagons to transport the coal.

[23] Cyril Hart, The industrial History of Dean (Newton Abbott: David Charles, 1972) 269.

[24] Ralph Anstis, Warren James and Dean Forest Riots (London: Breviary, 2011); Chris Fisher Custom, Work and Market Capitalism, The Forest of Dean Colliers, 1788-1888 (London: Breviary, 2016) and Chris Fisher The Forest of Dean Miners’ Riot of 1831 (Bristol: BRHG, 2020).

One reply on “Blowing up the Fire Engine”

So interesting. I knew Cyril Hart and have one of his books. The miners had it so hard and could barely feed their children. When I worked in the Forest they would tell me stories of the general strike of the 1920’s.