Author: ian wright

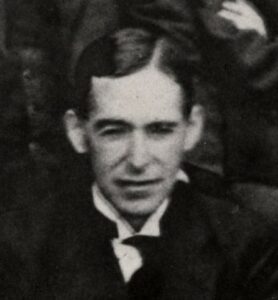

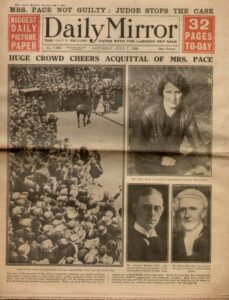

On 1 June 1928, Charles Fletcher was called into the witness box to give evidence in a sensational murder case, involving a wife accused of poisoning her husband with arsenic in the Forest of Dean. That was the only time he appeared in the national media but during his short life, he had made a big impact on those around him.

The article will utilise the story of Charles Fletcher, an orphan and political activist, as a lens to throw some light on events, institutions, organisations and social movements which impacted life in Bristol, Chepstow and the Forest of Dean at the beginning of the 20th century.

The childhood of Charles Fletcher was dominated by trauma and his adult life by poverty. Fragmentary references to his life can be found in the admission records at the Muller Orphanage in the Bristol and Forest of Dean newspapers and Ancestry. This article will attempt to piece together his life story from these fragments and pay tribute to a man long forgotten who lived in poverty but believed in internationalism, social justice and equality.

As a young man, Fletcher decided he would devote himself to improving the conditions of his fellow workers in the mines of the Forest of Dean where he became attracted by socialist politics. He joined the Forest of Dean Miners Association (FDMA), then briefly the Communist Party and the Miners’ Minority Movement and was a key activist during the 1926 lockout. Just before he died in 1929, his name appeared in national newspapers as a key witness in one of the most sensational murder trials of the decade.

An Orphan

Charles Fletcher was born in Stroud on 2 June 1892. His father, Charles William Fletcher worked as a servant and gardener and his mother, Clara Sophia Fletcher (nee Butler), was a tailor. The family likely had Romany heritage because both Fletcher and Butler were well-known names among the gypsy community in the North Gloucestershire area. Fletcher’s grandfather traded in used cordage, bunting, rags, timber, metal and other general waste materials which was a typical gypsy occupation. His father died in July 1894 from pneumonia as a result of tuberculosis. Clara and Fletcher then moved to Barry in Glamorgan where some of her brothers lived. Clara started a relationship with Josiah Jones and possibly married him towards the end of 1898.

However, on 25 January 1899, Clara also died from tuberculosis. Josiah said he did not want to take responsibility for the boy so it was agreed that Fletcher would go and live with his maternal aunt, Sarah Ann Lear, who already had six boys and lived in Stroud. Sadly, Sarah’s husband died while she was attending Clara’s funeral. Sarah was now a widow, dependent on parochial relief and ill with bronchitis. As a result, she was not in a financial or emotional position to look after Fletcher, but he remained in her care for six weeks.[1]

Muller Orphanage

Fletcher was then admitted to the Muller Orphanage in Bristol on 7 April 1899 which was run by the Plymouth Brethren and the evangelical principles of its founder George Muller. The orphanage was funded by donors and legacies. Fletcher qualified for admission because he was the legitimate offspring of a married couple who had died. He would not have been accepted if he was ‘illegitimate’ because the orphanage wanted to discourage the notion that children from a ‘promiscuous union’ could be cared for if abandoned by their parents.[2]

It must have been a forbidding and intimidating experience for Fletcher to arrive at the austere orphanage with its enormous grey institutional buildings sitting isolated in the countryside just outside Bristol near Ashley Down. Muller’s five orphan houses were all built on a similar plan and were self-contained, having their own laundries and medical facilities.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the orphanage had become a massive enterprise caring for nearly 3,000 children and employing over 200 staff with many of them living on site. Despite the history of abuse associated with institutions caring for children, there is no record of ill-treatment of the children at the Muller Orphanage and there is no reason to believe that the staff were not kind and loving to the orphans. However, the rules were strict and the children who were admitted to the homes could be dismissed for bad behaviour or returned to their Parish Unions if they were too ill to be cared for adequately by the orphanage.

The children were reasonably well educated for their social class and were taught reading, writing and religious education based on Plymouth Brethren scripture. The girls were taught domestic skills with a view to employment as poorly paid cleaners and housekeepers for the middle and upper classes. The boys were taught skills that could enable them to have a trade or gain work in industry or agriculture. The daily schedule was rigorous by contemporary standards, but the children were well-fed and cared for. The grounds were used for the cultivation of vegetables where Fletcher would be put to work in the evenings. [3]

The girls remained at the orphanage until they were eighteen, but the boys were apprenticed out to a trade or maybe to a farm when they were fourteen usually with board and lodgings and minimal pay. The orphanage sought out potential employers who were also of the Plymouth Brethren faith and the children were rarely returned to their own extended families where it was believed they might be exposed to secular and amoral influences.[4]

On 26 October 1906, at the age of fourteen, Fletcher was sent to work for Mr Williams at Chapel Hill Farm near Pembroke in the middle of the Welsh countryside. In 1908, when he was sixteen, he came to live in the Forest of Dean and got a job working for James Simmonds at Longley Farm, near Clearwell. In 1911 he was working for James Teague as a cowman at Trow Green farm also near Clearwell. In 1915. he moved to Milkwall near Coleford and took up work in a coal mine and became involved in socialist politics.

Forest of Dean

When Fletcher arrived in the Forest of Dean socialist politics were beginning to be discussed within the working-class community and the Liberal consensus in the Forest of Dean was challenged by the establishment of local Independent Labour Party (ILP) branches. Fletcher would soon become involved in Labour and socialist politics and would have got to know some of the people involved, particularly in the Coleford area where he lived. Some of these people were members of the ILP and some of them would later join the British Socialist Party which Fletcher also joined.

Independent Labour Party

The ILP was established in 1893 to create a working-class organisation politically independent of the Liberal Party.[5] In 1908, an ILP branch was formed in Lydney. In 1910 and 1911, more branches were opened in Coleford, Cinderford, Yorkley, Parkend and Bream.[6] The main political base for the ILP was in West Dean around Lydney and Coleford. The membership included railway workers such as James Birt and Edwin Rennolds from Lydney and Jim Jones from Cinderford, tin plate workers such as George Powell and quarry workers such as Arthur Sheldon and Fred Kear.

Not all members of the Forest ILP were industrial workers as shopkeepers and tradesmen also joined the party. Arthur Hicks, a bootmaker, was elected the secretary of the Coleford branch of the ILP in 1910.[7] Also active was Tom Liddington an insurance worker who in the past had worked on the railways and mines and William Morris (nicknamed the oldest socialist in the Forest) who ran an ironmonger’s shop in Coleford. The main organiser of the ILP in Lydney in 1908 was Mrs T Adams. Fletcher Hallam from Littledean House provided accommodation for visiting speakers in East Dean.

In 1911, some socialist women organised a branch of the Women’s Labour League in the Forest of Dean. The League had been founded in 1906 to promote the political representation of women in parliament and local bodies and was affiliated to the Labour Party. These included Ellen Hicks, Mary Liddington, Annie Tomlins, who was a schoolteacher, and Annie Pope, who trained as a nurse and had been a member of the Social Democratic Federation, a small socialist and Marxist party founded in 1881. Annie Pope helped run the Waverley Hotel with her husband and Annie Tomlins was a resident at the hotel. In 1912 Ellen Hicks was elected to the Board of the Monmouth Poor Law Guardians.

Forest of Dean Miners Association

As a miner Fletcher would have been aware of how these developments led to conflicts within the Forest of Dean Miners Association (FDMA), the trade union representing the Forest of Dean miners who made up the biggest proportion of the workforce in the Forest. During the years from 1886 to 1918, the full-time agent for the FDMA was George Rowlinson who was a member of the Liberal party and closely tied to the political establishment and opposed attempts by the FDMA to affiliate with the Labour Party.

The FDMA was split between those miners, mainly from the Cinderford area, who supported Rowlinson and the Liberals, and those miners, mainly from West Dean, who supported the ILP. The West Dean miners active in the ILP included William Smith, Fletcher Luker, Reuben James, James Sayes, David Organ, William Hoare and Richard Kear.

The Sayes

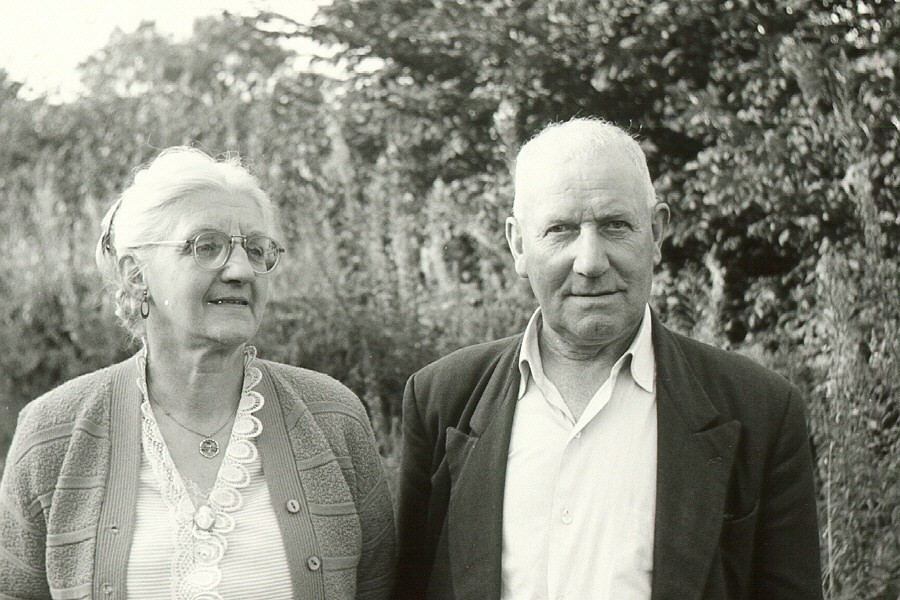

When Fletcher moved to Milkwall in 1915, he became friends with the Sayes family who lived in Ellwood which is very close to Milkwall. Elijah Sayes, who worked as a collier, was married to Emily Powell and they had four girls and seven boys. One of Elijah and Emily’s sons was James.

In October, over 300 miners at Wimberry Slade drift mine owned by the Cannop Colliery Company were involved in an unofficial strike over the use of 17 non-union men by the management.[8] James Sayes, the men’s checkweighman and a member of the ILP, led the strike. The checkweighman was elected by coal miners to check the findings of the mine owner’s weighman where hewers were paid by the weight of coal mined. Therefore, a checkweighman had to be someone whom the men trusted. He was elected by the workforce and as a result, he became the unofficial union representative at the pit.

The management took Sayes to court for breaking the terms of his contract and impeding the working of the mine. Sayes was fined by the magistrates and sacked from his job as checkweighman. Rowlinson, the miners’ agent, did not intervene on the men’s behalf and after three weeks with no strike pay, the men reluctantly returned to work.[9]

After James Sayes lost his job, he became active in the ILP and joined with others to try and establish a branch Labour Party in the Forest of Dean.

British Socialist Party

However, a small number of other foresters were looking for something more radical and joined the British Socialist Party (BSP) which was a Marxist political organisation established in 1911. The BSP argued for a specifically socialist and anti-capitalist programme as opposed to the more moderate Labourism of the ILP. Although many socialists were not ideologically rigid and tended to mix together in both organisations and this was the case in the Forest of Dean.

The Forest of Dean branch of the BSP was formed in 1914 with the affiliation of the Dean Forest Socialist Party which was based in Coleford and whose main activists included William Morris, Tom and Mary Liddington, Arthur and Ellen Hicks and Benjamin and Annie and Pope from the ILP.[10] Arthur Hicks became the secretary and Tom Liddington the President of the Forest of Dean BSP. By July 1914 they had about 30 members and held regular meetings throughout the Forest.

A well-attended public meeting organised by the branch was held in July 1914 at The Bailey Inn at Yorkley and presided over by Tom Liddington. The main speaker from London was Edwin Fairchild and he attacked the local Liberal MP, Harry Webb:

When the colliers of the Forest of Dean realised that Mr Harry Webb would no longer be their member in parliament – (hear, hear) – but they would have a man representing the working classes, who was prepared to stand on the floor of the House of Commons and say that until the workers of this country determined that they would be masters of the nation they must for ever remain poor (applause).[11]

Fairchild was on the left wing of the BSP but willing to work with the ILP and campaign for Labour Party candidates in districts where the BSP was not competing in elections. In the Forest, both the ILP and BSP supported the campaign for a Labour Party candidate at the next general election.

First World War

At the outbreak of war, the Forest of Dean BSP abandoned public meetings for a time, and in the Autumn organised study classes around issues such as industrial history, logic and readings of Marx’s theory of economics in Capital.[12] In May 1915 the branch started organising public meetings again and in 1916 Fletcher joined the BSP.

Shipyards.

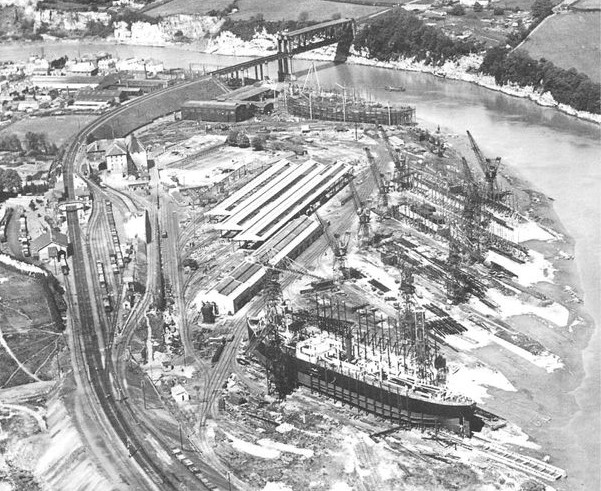

In 1917, the government set about building National shipyards at Chepstow and Beachley to help replace the huge losses of shipping by German U-boat attacks. The plan was that the National Shipyards at Chepstow and Beachley would be developed as a nationalised industry by expanding an existing shipyard which had been established in 1916 by the Standard Shipbuilding Company. The ships would be assembled by civilian labour, but the new yards themselves were to be built by the Royal Engineers and German prisoners of war. Some 6,000 Royal Engineers came into the area to develop the shipyard.

About this time, Fletcher obtained better-paid work as a plater’s helper at one of these shipbuilding yards where, as a munitions worker, he would be exempt from conscription. In May 1918 the workers at Finch’s yard in Chepstow passed a resolution against their yard being taken over by the military. On 6 June 1918:

over 2,000 workers, including all Finch’s shipyard workers and the men employed on the military hospital, attended a mass meeting held on the Institute football ground, to protest against the Government proposals of conscript labour in the national shipyards…. Delegates were present representing the whole of the trade union movement in the country, including transport workers, railwaymen, shipwrights, navvies, dockers and miners… The whole of Labour was looking to Chepstow… to enter an emphatic protest against the employment of conscript labour in the national shipyards, the feeling amongst the workers being that it would lead to the conscription of labour generally….[13]

Just two weeks later, the Government climbed down and agreed that civilian workers, rather than the military and prisoners of war, would be used in the Chepstow and Beachley yards and so the Royal Engineers were evacuated while an influx of civilians to work in the shipyard was anticipated. Over 6,000 skilled workers eventually came to the Chepstow area from other shipbuilding areas, including Tyneside and Clydeside, and new housing was provided in three new garden suburbs.

The BSP had a very large base on Clydeside and shipbuilding centres elsewhere which saw the upsurge in industrial militancy during World War One. John Maclean, the BSP leader in Scotland, played a leading role in the Red Clydeside strikes. It is possible that Fletcher encountered other militant workers and BSP members who had migrated from Clydeside.

However, the management of the yards was marred by incompetence and it was not until October 1918 that the first ships were scheduled to be launched. In January 1920, the yards were privatised. The yards continued to build ships, but demand slumped after the war, and many of the workers faced years of unemployment.

Labour and Communist Parties

Meanwhile, in 1918, Rowlinson was voted out of office over his support for the Liberal Party and the conscription of miners and replaced by Herbert Booth a young miner from Nottinghamshire influenced by syndicalism. These developments contributed to the creation of a fledgling Forest of Dean Labour Party during the war and finally to the election of a Labour MP, James Wignall, in November 1918 who defeated the Liberal candidate, Sir Harry Webb. Over the next two years, the Labour movement grew in strength and there was optimism that it may be possible to build a land fit for heroes.[14]

After the victory of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia at the end of 1917 and the termination of World War One the following year, the BSP emerged as an explicitly revolutionary socialist organisation.

The war came to an end in November 1918 and many Forest families had to cope with the grief of the loss of their loved ones and this included two of the Sayes boys, John and Samuel.

William Durrant

In August 1920, the BSP negotiated with other radical groups to establish a unified communist organisation, an effort which culminated with the establishment of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB).

The majority of BSP members joined the newly formed CPGB and so Fletcher became a member of the CPGB at this time. A Chepstow branch of the CPGB was formed in October 1920 with William Durrant as the secretary. Durrant was born in Norfolk the son of an agricultural labourer. He initially became a train driver but like many other skilled workers migrated to work in munitions or shipbuilding.

In September 1921, there was a particularly nasty incident when a meeting of the Chepstow Communist Party held in the grounds of Chepstow castle was attacked by about 250 right-wing nationalists. The tensions in the town were probably exacerbated by the influx of a large number of skilled shipbuilders from other parts of the country. In addition, some Welsh miners had come to the CPGB meeting by train from the Welsh Valleys.

The nationalists were headed by the Tidenham brass band, singing the national anthem and with union jack flags flying. The march was led by an army officer who told the marchers to attack the meeting resulting in very violent hand-to-hand fighting. Durrant was beaten quite badly and then thrown into the River Wye. He only managed to escape death or serious injury by swimming to the other side of the river. The authorities did not intervene or make any arrests and the right-wing press celebrated the event.[15]

In 1921 Fletcher was living in lodgings with a family headed by a labourer and working as a self-employed chimney sweep. He remained in close contact with Durrant and members of the Chepstow Communist Party for the rest of his life.

1921 Lockout

Meanwhile back in the Forest, in April 1921, in response to a severe depression in the coal trade, colliery owners, supported by the government, slashed labour costs. Refusing to accept this cut in wages, a million British miners, including many war veterans, were locked out of their pits. The consequences for the 6,000 Forest of Dean miners, their families, and the whole community, were brutal. However, the miners fought a determined battle for an alternative that included public ownership of the mines with decent pay and conditions. One of the consequences was the departure of Herbert Booth as the agent of the FDMA and the arrival of John Williams in his place.

Williams was a young miner from the Garw Valley in South Wales also influenced by syndicalism. At about this time, Fletcher returned to the Forest to work in the pits and became a close friend and political ally of Williams. Sometime after the 1921 lockout, he moved back to the Ellwood area.

Miners Minority Movement

In 1922, in response to the loss of confidence after the 1921 lockout and the defeats that followed, the CPGB organised a series of conferences on the theme “Back to the Unions – Stop the Retreat”. It was proposed that organisations should be set up in each industry with a brief to provide a combative leadership to make industry-specific demands and reforms within the unions concerned, to give greater confidence to workers who wanted to fight back.[16]

It was decided that the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) would provide resources, organisation and strategy. The RILU was an international body established by the Soviet Union to coordinate communist activities within trade unions. The RILU had been formally established in 1921 and was intended to act as a counterweight to the influence of the Social Democratic International Federation of Trade Unions, an organisation branded by the RILU as class collaborationist.

As a result, the Miners’ Minority Movement (MMM) was launched in January 1924 with its paper, The Mineworker, and Nat Watkins as a full-time paid worker.[17] The MMM itself was not an attempt to set up a separate trade union but an attempt to coordinate the militant members within the MFGB, with the view of making it a more effective fighting organ in the class struggle.[18]

Soon after its formation, Fletcher and Williams joined the MMM, which provided them with an opportunity for support and tactical advice from other union activists from across the British coalfields. Fletcher was elected President and the Secretary was Jack Harris from Cinderford who worked at Eastern United Colliery and was a member of the CPGB as was his younger brother Len. Other MMM members were Albert Brookes, William Hoare and Albert Hoare from Bream and William Wilkins, Philip Elton and Albert Meek from Cinderford. These men set about building networks of sympathetic miners, distributed MMM propaganda and mobilised support for its policies.

The MMM immediately started to campaign for the transformation of the MFGB into a United Mineworkers’ Union based on industrial unionism which would recruit from all grades of mineworkers, including the craftsmen and was opposed to sectionalism and district agreements. It demanded a wage equivalent to that of 1914, adjusted according to the increase in the cost of living, plus 2s a shift and a six-hour day. The influence of the CPGB within the MMM meant that the MMM campaigned for the MFGB to affiliate with the RILU.[19]

Another prominent member was Arthur Horner from South Wales who would eventually be elected as General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) from 1946 to 1959 when the MFGB eventually became an industrial union in the form of the NUM.

The MMM achieved another victory with the election of Arthur Cook as secretary of the MFGB in May 1924. Not all MMM members, including Cook, were members of the CPGB, although the Party was the driving force behind the MMM. When Williams became a member of the MFGB Executive in 1924 representing the smaller districts, he became a close ally of Cook.[20] Although a member of the NMM and sympathetic to communism Williams never joined the CPGB and remained a member of the Labour Party throughout his life.

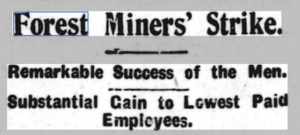

Strike

The first test for the MMM strategy in the Forest of Dean was when in 1924 the local colliery owners refused to implement a national agreement made by the MFGB and the organisation representing the colliery owners nationally. After months of local and national negotiations, Cook and the MFGB Executive gave the FDMA permission to issue notices of strike action.

A mass meeting was held at Speech House on Sunday 5 October 1924 and the strike commenced the next day and was generally supported by both union members and non-unionists. As chairman of the Forest Branch of the MMM Fletcher would have been heavily involved in organising the strike.

However, it was soon reported that 130 men had gone to work at Lightmoor Colliery. So, at midday, a large crowd assembled outside the town hall in Cinderford. The miners and their families were addressed by Williams who suggested they proceed to Lightmoor to persuade the men to stop work. The procession of about 1000 men and women, headed by the Excelsior Brass Band, marched to Speech House and confronted the men as they came off their shift. The blacklegs were told not to go to work the next day.[21] In his statement to Arnot Williams said:

The workmen at this colliery were ashamed to go to work the next day. The next morning we organised another demonstration headed by the town band to another colliery. This took place between five and six in the morning.[22]

In the meantime, on Monday, Williams was able to announce to a large crowd assembled at the Triangle in Cinderford that the employers at Cannop Colliery had agreed that the men could return to work at their pit the next day under the terms of the national agreement. No negotiations had taken place; the Cannop management simply announced that they were going to pay the workmen under the terms of the national agreement. The management of Parkend, New Fancy and Waterloo collieries followed suit.[23] However, at three of the major collieries, including Lightmoor, some men were still strike-breaking.

A meeting was held at Speech House on Tuesday afternoon attended by a large crowd of miners and their families. The FDMA President, David Organ, announced that the tactics appeared to be working. The management at Princess Royal had now accepted the terms of the national agreement. There were still a few men working at the remaining pits including some craftsmen and the safety men. He urged the men to organise pickets but to use peaceful means to persuade them to come out. The following day the management at Norchard announced they had accepted the terms.[24]

The Crawshay group of collieries still refused to accept the terms. However, on Friday the directors of the Crawshay group and Crump Meadow Colliery caved in, signed the National Agreement and agreed to an audit of their books. The strike was a massive victory and was over in just one week.[25] The result meant the Forest miners received back pay up to a total of fifty thousand pounds with an agreement that there would be no victimisation.[26] The only colliery not to confirm was the small Wilda Colliery in Bream where the men remained on strike for another four weeks before their owners backed down.[27]

Parliament

On 10 June 1925, the Forest community were informed of the sudden death of their MP, James Wignall. On the following Sunday, the Executive Committee of the Forest of Dean MMM met and a motion was put forward by Fletcher and seconded by Albert Hoare that they should nominate Williams to stand as the parliamentary candidate in the coming by-election. Elton, Wilkins, Meek and Brookes all spoke in support of the motion. Williams responded by saying he accepted their support with certain reservations. The following week Cinderford Labour Party and the FDMA Executive also nominated Williams to stand. Williams believed that the industrial struggle was far more important than parliamentary politics and so after careful consideration, he turned the offer down:

Alluring though the temptation may be to stand for parliament, I am compelled to decline the invitation to allow my name to be submitted to the Selection Committee to be held on Saturday next. Judging from information leaking through very authoritative channels the miners will be shortly confronted with a demand from the owners to return to a working day of eight hours and a revision of the wages agreement. I, therefore propose to play a full part in the coming crisis. To that end, I withdraw my name as a candidate for Parliament, that I may work more efficiently for the miners.[28]

Red Friday

Williams was correct about the coming crisis and on 25 June 1925, the colliery owners nationally gave notice to terminate the 1924 wage agreement.[29] The colliery owners proposed wages be cut and hours worked increased.[30] In the Forest of Dean where, except for Somerset, wages were the lowest in the country, this would mean a reduction in wages of approximately 15 per cent. Williams attended the MFGB national conference on 3 July where he supported the decision to reject the owners’ terms.[31]

Organ, speaking at the miners’ demonstration at Speech House in July, said:

the Forest of Dean miners had been under a cloud this past year and were struggling hard to obtain the arrears they were due under the national wage agreement. They had now got those arrears but clouds still hung over them and unless the mine owners made very different proposals to those already offered, he could see nothing but a bitter struggle in front of them.[32]

Richard Kear proposed a resolution that unreservedly rejected “the monstrous proposals” made by the coal owners. The meeting pledged that they would not accept a reduction and would fight for wages based on the cost of living.[33]

On 18 July, members of the Forest of Dean Colliery Owners Association (FODCOA) gave notices to end the existing agreement from 31 July 1925.[34] Similar notices were issued by colliery owners across the country and at the same time opposition spread. Negotiations took place, but the government insisted it would not provide a subsidy and the owners refused to back down from their plans. It looked like the miners were going to be locked out again as they were in 1921.

The MFGB received the backing of the TUC Council and gained the support of the transport and railway unions who pledged to stop all movements of coal from 1 August if the owners locked the miners out. The government were not yet ready for all-out class war and so backed down, and on Friday 31 July announced they would provide a nine-month subsidy for the coal industry to enable the employers to maintain wages and conditions.

A condition of the subsidy was that the MFGB accept the role of a Royal Commission into the coal industry to make recommendations to put it on a sounder economic foundation. The Daily Herald called the government announcement Red Friday in contrast to the Black Friday defeat four years earlier.

At a mass meeting at Speech House on Sunday 2 August, the Dean Forest Mercury reported Williams was sceptical and argued they should have insisted on a wage rise linked to the rise in the cost of living plus the 2s Sankey award as put forward by the MMM. He warned:

We have been told this was a great victory. I would ask in which respect is this a victory? You are to work for nine months with wages about 15 per cent below the cost of living based on 1914 … He hoped his hearers would notice the date. The settlement was going to last until next May. In nine months’ time, this country would be stocked with coal, and they would begin their struggle in May. Do not let them forget they began their last defeat in April. An enquiry has been set up. The coal industry has been cursed with enquiries. They had had the Sankey, the Buckmaster, the Macmillan enquires, and now they were going to thrust another one on them. What were they going to enquire into? What were they going to discover? [35]

William Hoare and Fletcher said they agreed, and a resolution was passed with unanimity that the meeting considered the settlement unsatisfactory and expressed disappointment that the MFGB Executive did not stand by a demand for wages equal to the cost of living.

Meanwhile, the left within the MFGB was attempting to build up its strength because it suspected the government was just playing for time. By August 1925, over 200 MMM branches had been established, and 16 lodges had been affiliated.[36] Fletcher and Williams attended an NMM conference on 29-30 August where Tom Mann argued:

We have to ask ourselves, are we prepared to meet the opposing forces when the next round begins? We must be frank about it and admit that at present we are not ready. The engineers feel keenly the absence of fully disciplined forces capable of national and international action, and the miners will require a much more highly disciplined regimentation of the organized forces of the workers when the next battle begins.[37]

During the conference, Williams argued that the MFGB Executive was wrong in accepting the settlement and not taking advantage of the situation:

I think we have had the chance of our lives in this question. We have had the chance to wrest ourselves from capitalism, we had more than that, we have had the chance to bring about a real genuine revolution.[38]

The Royal Commission was appointed on 5 September under the chairmanship of the Liberal politician, Sir Herbert Samuel and only had three members none of whom were representatives of the miners.

The FDMA Executive meeting held on 6 October agreed that Williams should take up a seat on the National Executive of the MMM. On 10 October, there was an NMM conference in Cinderford where preparations were made to build up the strength of the FDMA for the coming fight.

1926 lockout

Members of the Forest of Dean mining community lived either in one of the three main towns of Cinderford, Coleford and Lydney or in scattered villages or hamlets. The area which includes the settlements of Ellwood, Milkwall and Marsh Lane consisted of less than a hundred scattered dwellings where most of the men and boys worked in mines or quarries. Each of these small communities became dependent on its own resources and this was the case for the small village of Ellwood which was made up of about twenty-five houses. Fletcher was now living on his own in a house in Holly Lane in Ellwood next door to Fred and Bertha Thorne.

The Thornes were originally from Cinderford but like hundreds of other Forest of Dean mining families had migrated to South Wales in the 1880s where wages were better. Fred followed in his father’s footsteps and became a miner. On returning to the Forest to live in Ellwood Fred volunteered his labour as a healer and a masseur. He helped a neighbour’s child who was badly injured recover. He went by every evening to massage the boy’s leg and over time the boy learnt to walk again when doctors had given up hope.[39]

Fletcher devoted his energies to helping out in the local community and working with the Sayes family and Thornes helping to feed the children. Cyril Elsmore who was a schoolboy at the time of the lockout recollects:

Most of the working population were miners employed at the various pits in the district. Some safety men continued working to maintain the conditions in the pits. The few exceptions who were not miners were Forestry Commission employees. It quickly became apparent that children needed food. Our headmaster, Mr Joseph Pope, called a meeting of parents. The response was very good. They formed themselves into working parties and the Chapel schoolroom was taken over. Among the main stalwarts were Elijah Sayes who was responsible for the room and lighting the fire and cooking, and Charlie Fletcher who was brought up in Muller Orphanage in Bristol and came to Marsh Lane to learn the trade of mining. He did all the menial jobs. He always brought Mrs Thorne’s dog, who usually lay on the grass in the cemetery, but one day he wandered around and someone stumbled over him carrying hot water and scalded his back. Charlie took off his coat and wrapped the dog up and took him back to his cottage. He looked after him and because his back was bare of any hair Mrs Thorne knitted several jerseys for the dog to wear until he was well.

Poor Law Relief

A minimal amount of relief for the destitute in the Forest area was available from the Board of Guardians at Westbury for East Dean and Monmouth for West Dean. In addition, the destitute living in the Ruardean area were required to apply for relief from the Ross Board of Guardians. Relief money was raised through the rates and the lockout meant that the collecting of rates was hampered by the level of poverty in the community.

Striking or locked-out miners were not considered by the authorities to be destitute because they were deemed to have refused work. However, their dependants such as wives, children and widowed mothers could be helped if they were in severe need. Any money coming into the house from other sources such as an older son or daughter was deducted from the weekly allowance and relief was denied to those who had savings or owned their property.

Consequently, no relief was available to able-bodied single men unless they were destitute and physically incapable of work in which case, they could only be offered a bed in the workhouse. Single men often lived in lodgings or with family members and so became dependent on the families with whom they lived adding an extra burden to those households. During May, hundreds of families from the Forest applied for relief and some relief was paid out to wives and children of miners in food vouchers or cash and initially only for two weeks.

The issue of relief became a highly controversial issue during the lockout as more and more families became dependent on relief to survive. The Labour members on the Boards, who were in a minority, did their best to challenge the legality and morality of the decisions made by the majority of the guardians who were mainly from upper or middle-class backgrounds. Most of these guardians had spent many years sitting on committees and were well-versed in using legalistic arguments and bureaucratic manoeuvres to undermine those Labour members who were less knowledgeable or experienced.

Monmouth Guardians

Lady Mather Jackson was the chair of the Monmouth Board. She was the wife of Sir Henry Mather-Jackson 3rd Baronet who held extensive business interests in mining and railway infrastructure.[40] In terms of social class, privilege and vested interest Fletcher and Mather could hardly be further apart. Mather’s level of awareness, her ignorance and her lack of experience of working-class life would have meant she could not comprehend the poverty and suffering within the mining community in the Forest of Dean.

An emergency meeting of the Monmouth Board was held on Wednesday 12 May. The Board was chaired by Mather who confirmed a weekly allowance of 10s for a miner’s wife and 3s for a child in the form of a loan up to a maximum of 25s per week.

A J Wilke, the relieving officer for the Monmouth Board, said that he had already dealt with 200 cases at an average cost of one pound per case paid out in vouchers at the above rate. He added that on Tuesday 4 May the applicants came to the Yorkley station, and he told them he could not relieve the able-bodied men. He said he had been stopped at his house and held up by a crowd of miners. After collecting more food vouchers from Monmouth on Friday he complained that:

When I got home at 5 o’clock I was besieged … On Saturday night I could not do anything with them. The police came down and since then I have been under police protection.[41]

The 30 members of the Monmouth Board included nine Labour members who were sympathetic to the miners; Fletcher Luker (ex-miner), Ellen Hicks, Albert Brooks (miner), Miss Taylor, E Beard, E Pritchard, A Brown, E J Flewelling and H J Smith. E W Neems who was among the fifteen members from the Forest who was also sympathetic argued that:

It was not the spirit of the men that made trouble for the relieving officer it was a necessity. There are people starving who are too proud to come here. You cannot drive poverty into the ground. If we do something it will prevent a more serious outbreak.

A motion that the 5d a day for the school meal provided by the County Council should be deducted from the 3s allowance per child was defeated. One of the members of the board who voted for the motion was William Burdess who was the underground manager at Princess Royal Colliery. Luker moved a motion at the meeting that the government should provide £20,000 to cover the extra costs of providing relief but this proposal was rejected. Two committees of six were appointed to review the applications.[42]

On Wednesday 2 June, Mather informed a meeting of the Monmouth Board that a meeting of the Special Relief Committee had received a deputation consisting of four representatives of the miners from West Dean including William Hoare and Fletcher who requested that:

That assistance should be given to the man.

An allowance should be allowed for rent.

That the income to the home such as from sons and daughters should not be taken into account.

That person owning their own houses should be relieved less a fair reduction for rent.

War pensions should not be taken into account.

Relief should be given to single men (particularly as they often lived in lodges with people who are also receiving assistance).[43]

In response, Mather Jackson quoted the regulations to justify her rejection of all the above requests.

Hicks reported cases of men she knew who owned their own houses and so had been denied relief and who were now close to starving.

Russian Money

On Wednesday 2 June, a mass meeting was held at Speech House. Organ said the main item on the agenda was the issue of allocating the money donated by Russian trade unionists. The issue to be debated was whether some of the money should go to miners who were not members of the FDMA. It was soon clear that the majority would vote for the money going only to FDMA members.

Fletcher spoke first and admitted he initially supported the donation to non-unionists but at the time he was under the impression there were only about 3 per cent were not paid-up members and now having learnt the figure was more like 7 per cent he had changed his mind. He said:

He had come into contact with men who for many years had paid their union, three for 45 years, and they had received very little benefit indeed in strike pay, and these were the most entitled to benefit now.[44]

Long March

On Friday 4 June, for the second time in three days about ninety people, mainly single miners, walked ten miles from Bream to the Board’s offices at Monmouth to put their case for relief. Many of them were weak from a lack of food.

While the people waited outside, Mather continued to insist that the regulations forbade them from giving relief to able-bodied single men. The Labour members attempted to challenge the legality of the decision. Albert Brookes pointed out:

There is more now more destitution. They are being refused anything and they are absolutely starving. The situation is serious.[45]

After a discussion over the legality of the situation, a deputation of four miners was invited into the meeting including Fletcher and Hoare who argued the same points as before but added that an extra allowance was needed to cover rent for housing. He asked at what point does a man become destitute and in response, Mather said it was when he was physically unfit. Hoare responded, “that physical unfitness and destitution are two distinct things”. He finally said:

That the married men and single men were receiving nothing and therefore must be destitute and that was why they had come there that morning to either claim relief from outside or admission into the institution which they contended the law entitled them to. [46]

Mather said that in some cases the relieving officer could pay rent in kind. However, she repeated her claim that the regulations forbade guardians from relieving single men and only the wives and children of married men. Hoare replied if that was the case how come Gateshead Union were providing relief to single men with the sanction of the Ministry of Health? He added that he knew of cases of families being so far behind with their rent they faced eviction.

Mather then claimed that before the lockout a miner with three sons could be earning £10 a week and therefore must have undeclared savings. Fletcher responded to Mather’s accusation:

The wages of a colliery labourer in the Forest of Dean would not average more than 25s to 27s a week. Five days was the most the colliers work in the Forest. The wages during the past four or five years had been very low and the conditions had also been bad … He could not conceive of £8 or £9 going into any house of any man working in the Forest collieries at this time neither could he conceive, after having done no work for five weeks, they could have any money.

Luker fully backed Fletcher’s statement and argued that the Board should do everything in its power:

according to the law and to the means at their disposal… and deal with the applications sympathetically and justly.

Mather responded that unless a man was physically unfit, they could not relieve him. G F Park said that many of the men drawing relief in the Forest of Dean were doing very well and ran flocks of sheep, while A Brown backed up the statements by Fletcher and Luker. Brookes added that the Board should “use common sense rather than an official attitude to in regard to these men who were genuinely unemployed”. Luker proposed the following motion which was seconded by Miss Taylor and Ellen Hicks:

That this Board of Guardians recognising the need for more generous dealing with able bodied men in the case of industrial disputes asks the Minister of Health to confer greater powers on Boards as to enable them to give immediate relief so that needless suffering can be avoided.

Park made some remark about how long they were going to be on strike and Brookes responded: “Mr Park’s suggestion is that they be starved back to work.” When it went to a vote nine members voted for the motion and nine against with some abstentions but after a long discussion, a second vote produced a majority in favour of the resolution.

The deputation was then asked to return to the Board room and Mather informed them that if anyone could obtain a certificate from a doctor confirming they were physically unfit then they could get relief on a day-to-day basis. Mather also said the men who had made the journey this morning could be offered a meal of bread and cheese provided they gave a commitment they would leave the premises and not return.

After Hoare consulted with men outside, he informed Mather that unless they got a more favourable response they intended to stay. He added:

You know as well as we do that the Minister of Health is trying to override the Poor Law and is cutting it down. He is the willing tool of the coal owners trying to starve us into submission … Therefore, to us, there is nothing in that decision requesting the Ministry of Health to allow you. You already have got the power. You are within the law despite the Ministry of Health.

Mather said; “We haven’t got the power”. Hoare was aware that in other districts such as the North East of England where there was a Labour majority on the Board of Guardians single locked-out miners had been awarded relief and therefore responded:[47]

The Ministry have sanctioned a rate relief at Gateshead equivalent to unemployment pay. In any case, your decision to get sanction from the Ministry of Health to extend relief does not mean anything to us. We consider that you have the power, and it is for you to decide now. Anyway, that is what I am instructed to inform the Board, that unless you do something for us, to remain here.[48]

Fletcher said:

He did not know if they could stop the men from coming to Monmouth at some future occasion but they would see what they could do to only send a deputation down. He expected they would be coming there and demanding admittance. The men had five weeks’ practical experience of the conditions They will not go under lightly, and they are prepared to starve on top, and they will gladly let you bury them. They have had enough burying underground.

Hoare added that several men who were here on Wednesday could not make it because they “are too stiff, sore and weak”. Mather told Hoare that he should tell the men what the Board had done and that they should leave quietly. He responded:

Very well we will give the men your position, and of course, it rests with them. Before we go, even if the men outside decide to leave, I want to register a protest here. We consider that you already have the power to do more than you are doing.

When Hoare reported back to the men one said: “If we have to die, let us die here”. After eating their bread and cheese they walked home. Some of these men had fought in World War One and it is hard to imagine what they thought of their country now. At the end of August, the Monmouth Board refused to give any relief even to destitute miners’ wives and children. Many miners and their families were now struggling to survive and were short of food and there began a drift back to work in the Forest of Dean and some other areas.

In response, the MMM urged the conflict should be intensified by the withdrawal of safety men, the prevention of outcropping, an embargo on foreign coal and the introduction of a levy on all trade unionists. Despite opposition to the MMM’s approach by both Cook and Smith, the strategy was endorsed by 460,150 votes to 284,336 in a district ballot.[49] The result reflected the influence of the MMM within the MFGB at the time. Those districts in favour were the Forest of Dean, Derbyshire, South Derbyshire, Durham, North Wales, Scotland and South Wales.[50]

The lockout lasted until December 1926 when the miners were starved back to work. In 1927 the trade union movement went into a period of retreat combined with recrimination and division. The MMM and the CPGB came under increasing attack from the right wing of the Labour movement and in some areas where the CPGB was not very strong activists became increasingly isolated and estranged from the broader trade union movement. Consequently, Fletcher left the CPGB and joined the Labour Party. However, he continued to write articles for the newly established paper of the CPGB called Workers’ Life, a publication that attained a circulation of 60,000 copies a week by the summer of 1927.

The Trial of Beatrice Pace

On the morning of 10 January 1928, Harry Pace, a quarryman died after a long, painful and mysterious illness at Rose Cottage, the house he shared with his wife Beatrice and their five children in Fetter Hill between Milkwall and Ellwood. Harry and Beatrice were close friends with Alice and Lesley Sayes who lived nearby.

Although Harry’s doctor at first certified a natural death, a post-mortem conducted at the behest of the dead man’s suspicious family revealed that he had died from a large dose of arsenic. Dark whisperings began to circulate in the local community about hidden wealth, illicit lovers and threats of murder. This revelation brought not only fleet-street journalists but also Scotland Yard detectives to the Forest, and a lengthy inquest followed.

Just like many Foresters, Harry kept a few sheep and ran them on Forest waste claiming the right to common on Crown land. Every year he used arsenic to dip the sheep to prevent disease. Although it could not conclusively determine how the arsenic had found its way into his body, the inquest jury, in a controversial decision, charged Beatrice with Harry’s murder.

Harry had become ill over the summer of 1927 and was eventually admitted to Gloucestershire Infirmary where the doctors suspected he was suffering from arsenic poisoning. Fletcher was suffering from heart problems and had become quite ill. He got to know Harry Pace while they were both in Infirmary together and they became friends. When Pace returned home from the hospital Fletcher visited him twice a week to shave him and help take care of him. Fred Thorne also visited Pace every day except Sundays to give him a massage.

Fletcher was required to give evidence at the inquest where he said that he thought Harry‘s condition improved but only slightly during his time in the hospital and he was sent home on 27 October 1927. Fletcher added he often visited when he got home and he appeared to be getting better but when he visited him on 3 January Pace “was moaning and groaning and rolling about in bed”. Finally, when he saw him on 11 January 1928, the day of his death, Fletcher said “Pace was panting heavily and seemed in agony”.[51]

During the trial of Beatrice for murder, it became apparent that she was a victim of domestic abuse and this gave her a motive for the killing of her husband. In addition, and to add to the drama, accusations were also levelled against Lesley Sayes for having an affair with Beatrice and further suspicions were raised when it became apparent that Harry Pace had lent Lesley Sayes some money towards buying his house.

The trial was one of the most dramatic crime stories of the inter-war period followed closely by the national press. During the trial, busloads of people visited the area. In a sensational verdict, Beatrice was found not guilty. The story reflected the changing nature of the legal system, the role of the police, gender relations, the role of the media and attitudes towards domestic abuse in 1920s Britain. The events are described in the book by John Carter Wood, The Most Remarkable Woman In Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012). The book is excellent on the details of the case but somehow completely ignores the fact that the lives main characters are steeped in left-wing politics.

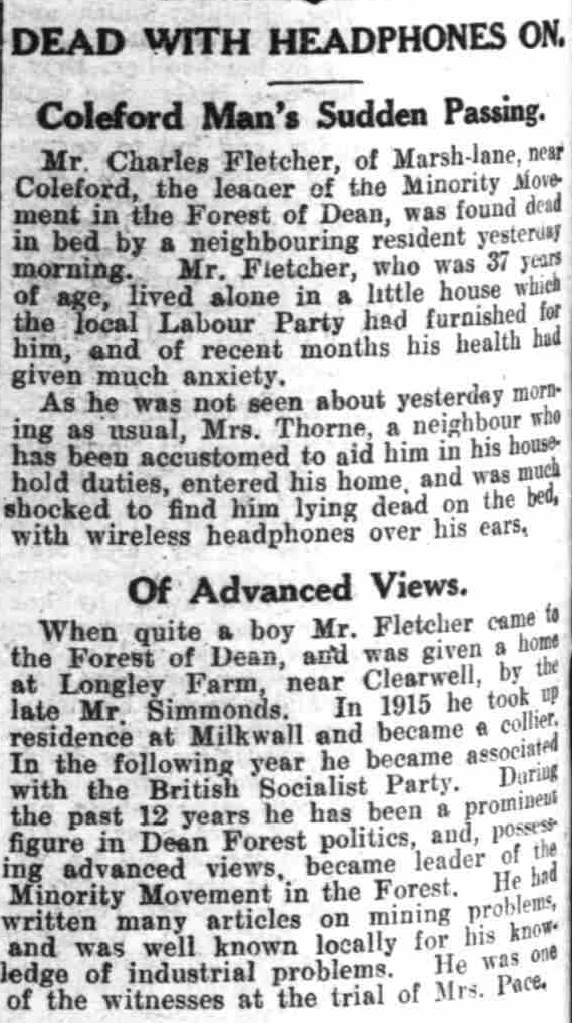

Death of Fletcher

After he came out of the hospital Fletcher moved into a cottage in Marsh Lane which Fred and Bertha Thorne had helped furnish with funds from the Labour Party. The Thornes took care of him and helped out with his housework and Fletcher often spent the evening with them.

On the evening of 12 November 1929 having spent the evening with the Thorne’s as usual, he returned to his cottage at about 9 pm. On the next day, Bertha called around to see him and found him dead on his bed with wireless headphones over his ears, the oil lamp still burning and with Emile Zola’s book Germinal with the page open at the dramatic point when water bursts into the pit after the anarchist Souvarine had sabotaged the entrance shaft following the defeat of the miners’ strike:

At the bottom of the shaft the abandoned wretches were yelling with terror. The water now came up to their hips. The noise of the torrent dazed them, the final falling in of the tubbing sounded like the last crack of doom; and their bewilderment was completed by the neighing of the horses shut up in the stable, the terrible, unforgettable death-cry of an animal that is being slaughtered.

Fletcher’s funeral was held at the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Ellwood and conducted by Arthur Williams and S Morgan from the Society of Friends (Quakers). An address was given by Williams on Fletcher’s sincerity and convictions adding he was a man of principle and one who believed in acting on them. Many branches of the Forest of Dean Labour Party were represented, together with members of the Transport and General Workers Union and Chepstow Communist Party. Beautiful floral tributes were sent by the local Labour Party, and the branches Coleford, Ellwood, and Chepstow.[52] At the end of the service, Fletcher’s friends gathered around the open grave and sang the Red Flag. The Dean Forest Mercury reported:

The death occurred on November 13th at a cottage in Marsh Lane, near Coleford, of Charles Fletcher who had resided in the Forest for many years and had become well known throughout the locality by reason of his advanced views and interest in politics … Over five hundred people attended his funeral and there were over forty wreaths which facts spoke eloquently of the esteem in which he was held by his fellow workers and the district generally for his loyalty to the workers’ cause and the staunch manner in which he held his principles.[53]

As a result of public subscriptions collected through the efforts of Fred and Bertha Thorne, a memorial stone was erected at the grave. The memorial takes the form of a chamfered Sicilian marble kerb erected on a plinth of Forest stone with the following inscription:

Erected by comrades and friends in memory of Charles Alfred Fletcher who died November 14th, 1929, aged 38 years. Worthy of remembrance.[54]

References

[1] Muller Orphanage admission records held at the Muller Museum.

[2] Darin Duane Lenz, Strengthening the Faith of The Children of God: Pietism, Print, And Prayer in The Making of a World Evangelical Hero, George Müller of Bristol (1805-1898), Doctor of Philosophy, Department of History College of Arts and Sciences Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas, 2010, 171-172.

[3] http://childrenshomes.org.uk/Muller/?LMCL=rYFsgb&LMCL=C6h5BH&LMCL=PzvGKN&LMCL=g2u1Vh&LMCL=j3l6ui&LMCL=NH4LJb&LMCL=efA57o&LMCL=D1NETN

[4] Thanks to Kate Brookes.

[5] The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave.

[6] J. Howe, “Liberals, Lib-Labs and Independent Labour in North Gloucestershire,1890–1914, Midland History”, Vol. 11, No 1. 117-137.

[7] Gloucester Citizen 19 August 1912.

[8] Gloucester Journal 7 0ctober 1911

[9] Gloucester Journal 14 October 1911.

[10] Justice 26 March 1914.

[11] Gloucester Journal 18 July 1914.

[12] Justice 6 May 1915.

[13] Guy Hamilton, Shipyards, scandal and pigstyes, Changing Chepstow in the first world war (Chepstow: Chepstow Society, 2017).

[14] Ian Wright, Coal on One Hand, Men on the Other, The Forest of Dean Miners and the First World War 1910 – 1922 (Bristol: Bristol Radical History Group, 2nd Edition, 2017).

[15] Cheltenham Chronicle 01 October 1921.

[16] Roderick Martin, Communism and the British Trade Unions 1924-1933, A Study of the National Minority Movement, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969).

[17] See the brief biography of Nat Watkins in the appendix.

[18] Martin, Communism and the British Trade Unions.

[19] Ibid.

[20] R. Page Arnot, South Wales Miners, Glowyr de Cymru: A History of the South Wales Miners’ Federation 1914–1926 (Cardiff: Cymric Federation Press, 1975) 244.

[21] Gloucester Citizen 8 October 1924.

[22] John Williams, A Statement, November 1961.

[23] Dean Forest Mercury 10 October 1924.

[24] Dean Forest Mercury 10 October 1924.

[25] Gloucester Citizen 8 October 1924.

[26] John Williams, A statement, November 1961.

[27] FDMA Minutes 14 October 1924.

[28] Gloucester Journal 20 June 1925.

[29] Gloucester Citizen 25 June 1925.

[30] Gloucester Citizen 3 July 1925.

[31] Western Daily Press 17 July 1925.

[32] Organ, The Life and Times of David Richard Organ, 21

[33] Gloucester Citizen 13 July 1925.

[34] Gloucester Citizen 24 July 1925.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Martin, Communism and the British Trade Unions, 37.

[37] Martin, Communism and the British Trade Unions, 67-68.

[38] Griffin, The Miners of Nottinghamshire, 141-142.

[39] Ancestry

[40] Sir Henry Mather-Jackson was chairman of the Alexandra (Newport and South Wales) Docks and Railway, chairman of the Marianao and Havana Railway Co., deputy-chairman Grand Trunk Railway of Canada, of the United Railway of Havana, Cuban Central, and Western Railways of Havana, of John Lancaster’s Steam Coal Co., and of the Powell’s Tillery Colliery Company, is also a director of the Ebbw Yale Steel Iron and Coal Co. and of the Rhymney Railway Co. He was an alderman and chairman of the Monmouthshire County Council, chairman of the Monmouthshire Quarter Sessions, Monmouthshire Standing Joint Committee, of the governors of the Monmouth Grammar School, and of the Monmouth Agricultural Institute, etc. During World War One he was chairman of the Military Appeal Tribunal. He lived at Llantilio Court, Abergavenny, and 56 Montagu Square, London, W.1.

[41] Dean Forest Mercury 14 May 1926.

[42] Gloucester Citizen 19 May 1926.

[43] Dean Forest Mercury 4 June 1926.

[44] Dean Forest Mercury 4 June 1926.

[45] Dean Forest Mercury 11 June 1926.

[46] Dean Forest Mercury 11 June 1926.

[47] Newcastle Evening Chronicle 13 August 1926.

[48] Dean Forest Mercury 25 June 1926.

[49] Gloucester Citizen 8 October 1926.

[50] Arnot, The Miners: Years of Struggle, 496.

[51] Gloucester Citizen 1 June 1928.

[52] Gloucester Citizen 19 November 1929.

[53] Dean Forest Mercury 22 November 1929.

[54] Gloucester Journal 25 October 1930.

Forest of Dean Transported Convicts

In the years 1789 – 1842 approximately sixty men and women from the Forest of Dean were transported to Australia mostly for committing minor crimes against property. The lists briefly outline the stories behind their transportation. This is ongoing research so there may be mistakes. I plan to add to more convicts and expand on their stories with further research.

Prosecution

The Justices of the Peace (JP) or magistrates had responsibility for law and order in each county. The post of JP started in medieval times, but became more important in Tudor times. They were unpaid and usually took on the role for prestige. JPs were usually landowners from the county who were appointed annually to the role. However, many did the job for years. The role also included a organising road and bridge repairs, checking weights and measures in shops, licensing ale houses, d supervising poor relief, etc. A JP had the authority to arrest a suspect on suspicion of a crime and interrogate them for three days.

Responsibility for the day to day maintenance of law and order still lay with local communities through the Parish Constable. The Parish, or ‘Petty’, Constable was appointed by the JP for a year. The post was unpaid and done in addition to the person’s usual day job. They were usually local tradesmen or farmers, which meant that communities were ‘policing’ themselves.

The majority of constables’ time was taken up with reacting to information given to them in the form of reports of crimes, or warrants issued by justices of the peace. They were obliged to execute all warrants for arrest and orders given through the courts, justices of the peace, sheriffs and coroners for their jurisdiction. In addition, they were expected to respond to allegations and reports of felonies committed, and arrest those who they witnessed committing felonies and misdemeanours.

The Parish Constable was expected to perform all of the main duties associated with local policing.

- Keep order in inns and ale houses.

- Keep the peace in the parish.

- Send illegitimate children back to their original parish.

- Impound stray farm animals.

- Arrest people who have committed crimes.

- Prevent crimes such as trespassing and poaching.

- Carry out punishments such as whipping vagabonds.

- Watch the behaviour of apprentices.

- Look out for vagabonds.

Local people were duty-bound to help the Constable if he requested it, keeping the community responsible for enforcing law and order.

Public prosecutors, empowered by the state to pursue the prosecution of criminals in England, were not introduced until as late as 1879. Prior to this, the victim had to find the perpetrator and detain them, often with the help of a local watchman, or constable, collect evidence and bring it before a JP, return to the jurisdiction for the trial, and provide witnesses if there were any. This was a time-consuming and costly process and so, for a private citizen to pursue a prosecution they must have been sufficiently motivated and/or wealthy enough to do so.

However, in 1818 an Act was introduced which empowered the courts to award an allowance for loss of time and expense to prosecutors and witnesses in the cases of felony. In 1926 another Act was introduced to extend this system to cover most misdemeanors.

The more minor offenses such as petty theft were dealt with summarily by magistrates at the petty sessions. For more serious cases such as murder, assault and theft, a larger number of JPs would meet four times per year at quarter sessions.

The most serious cases, such as murder and rioting and serious crimes against property, would be passed on to the assize courts, where a judge and jury would pass judgment and this could lead to a sentence of transportation or death. The sentence was usually fixed by the mandatory penalties of England’s Bloody Code, a series of statutes that prescribed capital punishment for many forms of theft and transportation for others.

Tickets of Leave and Pardons

There were only three ways in which the law might release a convict from bondage before the end of their sentence. The first was the ticket-of-leave. The convict who had been given a ticket-of-leave no longer had to work as an assigned man for a master and was also free from the claims of forced government labour. He could spend the rest of his sentence working for himself, wherever he pleased, as long as he stayed within the colony. The ticket lasted only a year and had to be renewed, and it could be revoked at any time. The second was a conditional pardon, which gave the transported person citizenship within the colony but no right of return to England. The third, though the rarest, was an absolute pardon from the governor, which restored him or her to all rights including that of returning to England.

A Certificate of Freedom

A Certificate of Freedom was a government-issued document given to a convict at the end of their sentence. This stated that the ex-convict had been restored to all the rights and privileges of a free subject and could seek out employment or leave the colony. Certificates of Freedom were introduced in 1810 and were generally granted to convicts, who had served their 7, 10, or 14-year sentence. Convicts who had received a life sentence could receive a pardon but not a Certificate of Freedom.

Charles Lees

Charles Lees (1860-1936) was born in Cinderford the son of a blast furnace worker and iron miner. He started work at an early age at Old Leather Pit. He then worked at Duck Pit owned by Crump Meadow company. After a short period at Lightmoor colliery, he moved to Crump Meadow colliery.

He married Minnie Penn in 1881 and had twelve children one of whom died as a baby.

Charles Lees was a trustee and committee member of the Forest of Dean Free Miners’ Association. He was a committee member of the Cinderford Co-operative Society and represented the mining community on welfare organisations such as the Forest of Dean General Accident and Health Insurance Society.

During World War One Charles Lee’s son George applied for exemption from military combat on the grounds of consciousness objection but this was rejected.

In March 1916, George Lees, Charles’s son, and the brothers Howard and William Nelmes were arrested for being absentee under the Military Service Act, having failed to report to barracks on receipt of their call-up papers. They all worked together as woodmen for the Crown Estate. They were brought before Littledean Petty Sessions chaired by George Rowlinson. Lees argued that he was a conscientious objector and asked to be exempted from conscription based on his Methodist religious beliefs. Rowlinson told him that he could have appealed before a military tribunal if he had made an application on receipt of his call-up papers but that it was too late now. They were all fined and handed over to the military.[1] Lees was drafted to the Gloucestershire Regiment and was seriously wounded at the front in October 1916.[2]

Charles Lees presented the following motion to a mass meeting of Forest of Dean Miners in August 1917 which was passed with a near-unanimous majority and triggered a series of events that led to the removal of George Rowlinson as the agent for the FDMA in 1918.

“That we, the Forest of Dean miners, call upon the various Trade Unions of this country to take the necessary steps with the view to ascertaining the views of the workers of all countries to negotiate an immediate and honourable peace.”

One of Charles Lees’ other sons, Oliver, was killed in Flanders in October 1918.

In 1921, he is listed as an overman at Crump Meadow and he worked there until it was closed in 1929.

[1] Gloucester Journal 1 April 1916.

[2] Gloucester Journal 14 October 1916.

William Stanley Wintle

William Stanley Wintle (1881-1971) was born in Yorkley. His first job was at New Fancy colliery. He started his railway career in 1899 working as an engine cleaner in Lydney engine sheds. He was promoted to a fireman (engine stoker) in November of the same year and then served as a fireman at Gloucester and Trowbridge. In July 1902 his finger was crushed while attempting to put a lump of coal in the bunker resulting in an amputation of the top of his finger.

He married Frances Howells in 1906 and had one child. In 1911 he was appointed as a driver at Llantrisant and then returned to Lydney in that capacity the same year. In 1919, he was elected as the secretary of the Lydney branch of ASLEF. In 1922 he was elected as secretary of the Locomotive Men’s Department Committee holding both positions until 1940 when due to his approaching retirement he resigned. He retired in October 1941.

James Edward Holford

James Edward Holford (1877-1957) was born in Lydney, the son of a railway guard. In 1901 at the age of 24 he was working as a railway brakeman and by 1911 he was working as a general foreman at Lydney docks. Finally in 1939 was working as a railway traffic foreman. He married Bessie Minnie Beatley in 1899 and had three daughters. He was an active member of ASRS and by 1907 was representing Lydney ASRS at regional and national meetings.

In 1905, he was elected to the committee of Lydney cooperative society. In 1906 he was elected as president of the Lydney Trades and Labour Association and was a member of the Independent Labour Party. He was made a magistrate in 1924 and continued in this role until 1928

National Union of Railwaymen

The National Union of Railwaymen came into being on 29th March 1913, the result of the amalgamation of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS), the General Railway Workers Union (GRWU) and the United Pointsmen’s and Signalmen’s Society UPSS).

The new union immediately attracted new members – with membership rocketing from 159,261 at the time of amalgamation to 267,611 by the end of 1913.

Discussions on amalgamation grew out of the 1911 national railway strike, which saw four key railway unions: the ASRS, GRWU, UPSS and the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF)) combine in a dispute for the first time. ASLEF was also involved in the first post-strike discussions on fusion, but left the talks after its proposals for a looser federation were not adopted.

For the duration of the First World War and its immediate aftermath, the railways were removed from the control of private companies and managed by the National Government. During the war, the NUR and ASLEF negotiated jointly with the government to win wage increases for railway workers, although at levels below the high rate of inflation. In March 1919 the government announced its plans to standardise and reduce the wartime rates of pay and, after failed negotiations with the unions, the second national rail strike began at midnight on 26-27 September 1919.

A key feeling during the strike was that sacrifices made during the war had not been acknowledged by the government – in the words of the NUR General Secretary, J.H. Thomas,

“the short issue is that the long made promise of a better world for railwaymen which was made in the time of the nation’s crisis, and accepted by the railwaymen as an offer that would ultimately bear fruit has not materialised”.

After nine days of strike action by the NUR and ASLEF, the government agreed to maintain wages at existing levels for another year. Subsequent negotiations resulted in the standardisation of wages across the railway companies and the introduction of a maximum eight-hour day.

The following is a list of some of the main characters in the early years of the ASRS and NUR in the Forest of Dean. Most of them are from Lydney which was a railway and port town.

Introduction

The National Union of Railwaymen came into being on 29th March 1913, the result of the amalgamation of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS), the General Railway Workers Union (GRWU) and the United Pointsmen’s and Signalmen’s Society UPSS).

The new union immediately attracted new members – with membership rocketing from 159,261 at the time of amalgamation to 267,611 by the end of 1913.

Discussions on amalgamation grew out of the 1911 national railway strike, which saw four key railway unions: the ASRS, GRWU, UPSS and the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF)) combine in a dispute for the first time. ASLEF was also involved in the first post-strike discussions on fusion, but left the talks after its proposals for a looser federation were not adopted.

For the duration of the First World War and its immediate aftermath, the railways were removed from the control of private companies and managed by the National Government. During the war, the NUR and ASLEF negotiated jointly with the government to win wage increases for railway workers, although at levels below the high rate of inflation. In March 1919 the government announced its plans to standardise and reduce the wartime rates of pay and, after failed negotiations with the unions, the second national rail strike began at midnight on 26-27 September 1919.

A key feeling during the strike was that sacrifices made during the war had not been acknowledged by the government – in the words of the NUR General Secretary, J.H. Thomas,

“the short issue is that the long made promise of a better world for railwaymen which was made in the time of the nation’s crisis, and accepted by the railwaymen as an offer that would ultimately bear fruit has not materialised”.

After nine days of strike action by the NUR and ASLEF, the government agreed to maintain wages at existing levels for another year. Subsequent negotiations resulted in the standardisation of wages across the railway companies and the introduction of a maximum eight-hour day.

The following is a list of some of the main characters in the early years of the ASRS and NUR in the Forest of Dean. Most of them are from Lydney which was at the time primarily a railway town with docks on the River Severn.

The National Union of Railwaymen came into being on 29th March 1913, the result of the amalgamation of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS), the General Railway Workers Union (GRWU) and the United Pointsmen’s and Signalmen’s Society UPSS).

The new union immediately attracted new members – with membership rocketing from 159,261 at the time of amalgamation to 267,611 by the end of 1913.

Discussions on amalgamation grew out of the 1911 national railway strike, which saw four key railway unions: the ASRS, GRWU, UPSS and the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF)) combine in a dispute for the first time. ASLEF was also involved in the first post-strike discussions on fusion, but left the talks after its proposals for a looser federation were not adopted.

For the duration of the First World War and its immediate aftermath, the railways were removed from the control of private companies and managed by the National Government. During the war, the NUR and ASLEF negotiated jointly with the government to win wage increases for railway workers, although at levels below the high rate of inflation. In March 1919 the government announced its plans to standardise and reduce the wartime rates of pay and, after failed negotiations with the unions, the second national rail strike began at midnight on 26-27 September 1919.

A key feeling during the strike was that sacrifices made during the war had not been acknowledged by the government – in the words of the NUR General Secretary, J.H. Thomas,

“the short issue is that the long made promise of a better world for railwaymen which was made in the time of the nation’s crisis, and accepted by the railwaymen as an offer that would ultimately bear fruit has not materialised”.

After nine days of strike action by the NUR and ASLEF, the government agreed to maintain wages at existing levels for another year. Subsequent negotiations resulted in the standardisation of wages across the railway companies and the introduction of a maximum eight-hour day.

The following is a list of some of the main characters in the early years of the ASRS and NUR in the Forest of Dean. Most of them are from Lydney which was a railway and port town.

William Darters

William Darters (1858-1931) was born in Whitercroft. As a young man, he gained work on the railways in Gloucester as an oiler and became involved with the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS). He married Emma Scrivens in 1883 in Gloucester and had nine children. He moved to Lydney and was elected as secretary to the ASRS and, in 1887, helped set up the Lydney Co-operative Society. He then started working as a manager for the Lydney Co-operative Society and continued in this role until his retirement. However, he continued to contribute to the ASRS remaining as secretary for about 17 years. Emma died in 1917 and in 1920 he married Rachel Eade. For many years he served on Lydney Parish Council.

William Harry Parsloe

William Harry Parsloe (1879-1963)

William Parsloe was born in Alvington, the son of a General Labourer. He worked as a boy in the paper mill in Alvington, and later for a short time at Lydney tinplate works. He then joined the service of the Great Western Railway Company at Lydney.

Parsloe spent five and a half years working in the London area before returning to Lydney. He then served at Chippenham where he was promoted to the position of engine driver and also at Gloucester.

He married Maria Price in 1904 and had two daughters, Winfred and Dorothy. For one period during the War, he was a member of the Lydney Rural District Council. Parsloe was also Secretary of the Lydney Trades and Labour Association and was Secretary of the Lydney Branch of the Independent Labour Party. He was an active member of Lydney NUR serving both as Secretary and President.

He later served as Vice-Chairman of Lydney Parish Council. He was a founder member of the now defunct Men’s Own Brotherhood. During his 42 years of railway service, Parsloe was an energetic member of the N.U.R. At different times he has been Chairman and Secretary of the Lydney branch and later as the Secretary of the N.U.R Approved Society (Lydney section). He for several years was actively connected with the Lydney Co-operative Society.