Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History reserve the copyright of this article but give permission for parts to be reproduced or published provided Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History are credited in full.

INTRODUCTION

At Wednesday’s meeting of the Miners Conference, now sitting in Nottingham, the butty system came under review and was universally condemned. One of the speakers characterised it as the worst evil under which the miner suffered, and another as the root of most of the miners’ grievances. The views of the Conference on the subject are to be embodied in their petition to parliament.

Gloucester Journal 17 November 1866

Recent years have seen the growth of subcontracting, piecework, self-employment, day work, zero-hour contracts, umbrella companies, minimum wages, and the use of agencies in a range of British workplaces. The driving force behind these apparent innovations is an attempt by companies to reduce labour costs and increase productivity.

This is not new. The sub-contract or butty system of working existed in the British coal mining industry from the early nineteenth century onwards until its demise in the mid-twentieth century. In the Forest of Dean, the butty system operated in most of the deep mines from the early nineteenth century onwards until it was finally abolished at Eastern United colliery in 1938.

The butty system in the Forest of Dean up to 1888 has been discussed in detail by Chris Fisher in his book, Custom, Work and Market Capitalism, The Forest of Dean Colliers, 1788-1888, and his article “The Little Buttymen in the Forest of Dean”, International Review of Social History, 25 (1980). Fisher discusses the impact of the butty system on workforce cohesion and solidarity, and how it increased the rate of exploitation of the workforce to the benefit of employers. This account of the butty system in the mining industry in the Forest of Dean will build on Fisher’s research by extending the period up to 1938.

Chapter One examines the concept of the independent collier, the contract or butty system, the various types of contract systems employed in the British coalfield and the role of the contract teams that worked on the coal face.

Chapter Two provides a summary of Fisher’s research covering the period in the 1870s and 1880s when Timothy Mountjoy and Edward Rymer were agents for the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association (FDMA), which was the trade union representing the Forest of Dean miners.

Chapter Three outlines the role of George Rowlinson, who was the FDMA agent from 1888 to 1918.

Chapter Four discusses the butty system in the Forest of Dean coalfield in the twentieth century and provides more detail on how the system worked. The discussion will be illustrated by oral history statements in Forest dialect from a cross-section of Forest miners to reflect a range of views on the topic, which reveal common features but also highlight complexity and contradictions.

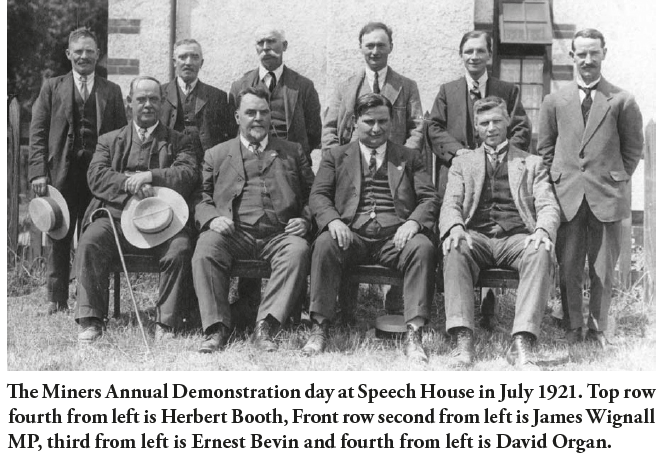

Chapter Five considers the role of Herbert Booth, who was the full-time agent for the FDMA from 1918 to 1922. Booth’s experiences in his native Nottinghamshire coalfield will be contrasted with those of the Forest.

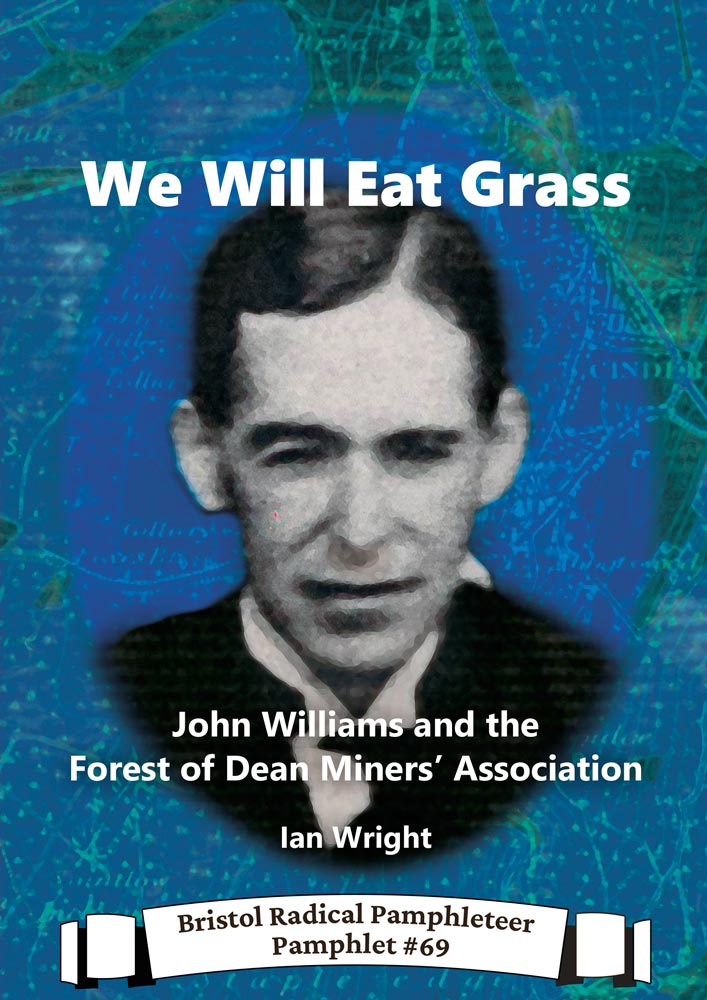

Finally, chapter six outlines the role of John Williams, the FDMA agent from 1922 to 1953 and the events surrounding the demise of the butty system at Eastern United in 1938.

CHAPTER ONE

THE INDEPENDENT COLLIER

One of the consequences of investment by mining companies in deep mining in the nineteenth century was a significant increase in the number of miners. However, until 1978, there was a common perception among many historians that miners had become wage labourers or ‘archetypical proletarians’. By this, they meant miners had turned into a uniform class of industrial wage earners with identical interests and status who, possessing neither capital nor production means, earned their living by selling their labour with little or no control over the day-to-day conditions of work.

Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, contrasts the `independent workman’ with ‘the collier’. The former is represented by the figure of the weaver or the shoemaker, who may still have a property in loom, linen or leather. The latter owns nothing but his ability to work, an ability which is seen as being perfectly indistinguishable from that of the ‘common labourer’. If the collier is more highly paid, it is not because he has any skill but is entirely due to the greater hardship, dangerous and difficult conditions and inconstancy of employment which characterise his work.[1]

Miners were perceived as living in occupationally homogeneous communities, sharing common work experiences and pursuing a common interest. As a result, miners were believed to have developed strong solidarity in their conflicts with their employers, who struggled to come up with strategies to undermine their demands for improved working conditions.

In 1978, Royden Harrison, Chris Fisher, and others from mining backgrounds challenged this view in their classic study of the nineteenth-century collier in their book The Independent Collier, The Coal Miner as an Archetypal Proletariat Reconsidered in which they explore, amongst other things, the butty or contract system of working in British coalfields in the nineteenth century and the role of miners as skilled artisans and small working masters.[2]

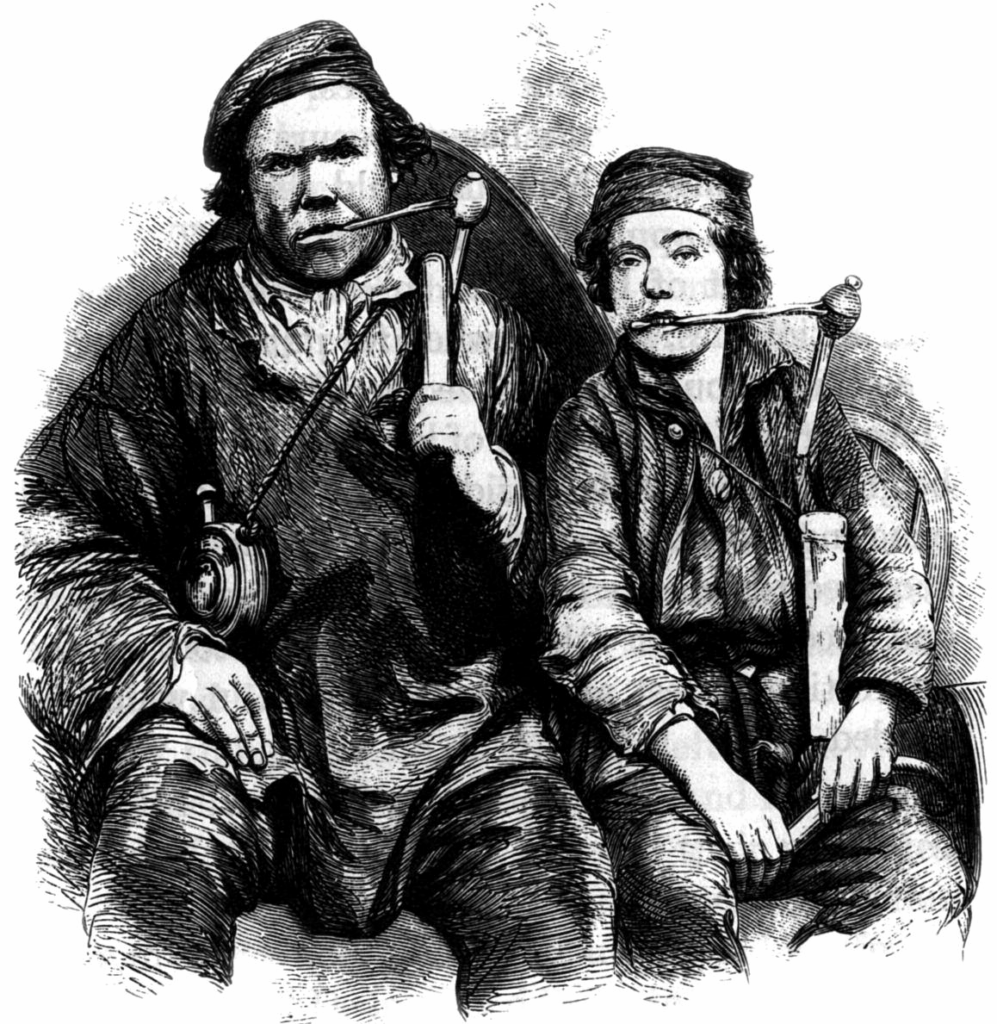

Hewers

In most districts in the British coal industry in the nineteenth and early twentieth there were large differentials between the various grades of workers employed in the collieries. The more experienced colliers or hewers who worked at the coal face extracting coal were highly skilled and were paid considerably more than most of the other workers in the mine. The hewers learned their trade on the job by working with the older, more experienced men.

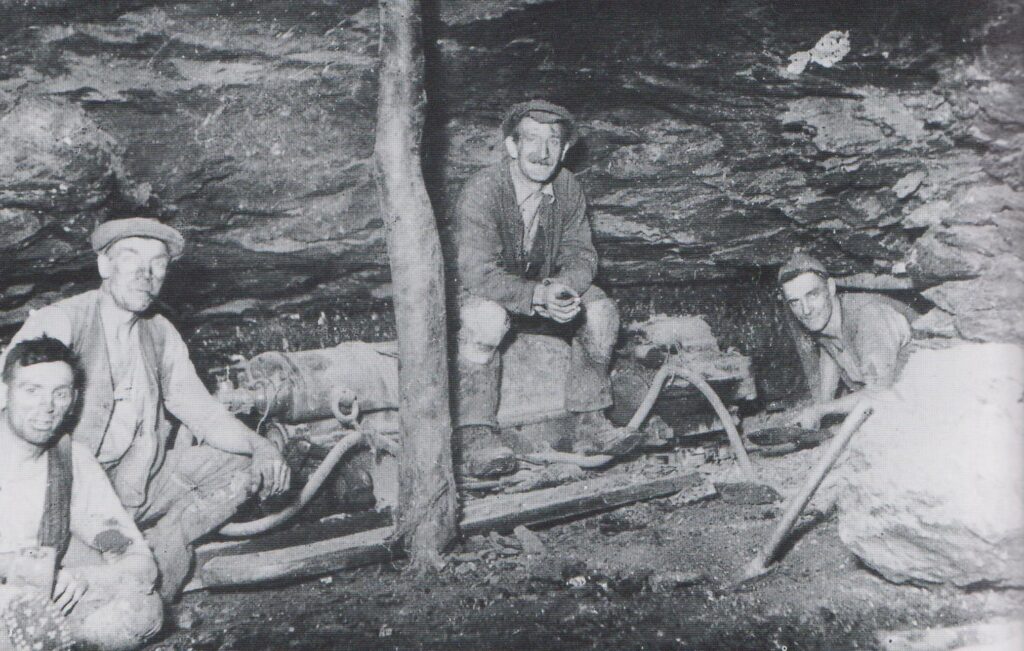

Up to the early to mid-twentieth century, hewing was done by hand using a pickaxe and other hand tools. The normal procedure for hewers was to cut a slot in the base of the coal seam so that coal would drop, or be coerced into dropping down under gravity. The roof immediately above the coal was also liable to fall and so hewers, being in the vicinity of this activity, were sometimes killed by accidental falls of coal or stone.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Forest of Dean, the hewing teams were led by buttymen who were paid by the ton of coal sent to the surface under a contract arranged with the colliery management. The buttyman employed men and boys who made up his team, called daymen, and he paid them a wage based on the days they worked. When demand for coal was up and prices were high and the conditions at the coal face were good, the buttymen’s earnings were usually much higher than the daymen’s.

Boys were often employed as hodders, who moved coal from the coal face to the roads, and trammers who filled the drams with coal, which were then transported to the shaft to be taken to the surface. A dram is an underground truck used for transporting coal.

The buttyman was allocated a ‘stall’ or section of the seam by the colliery manager. The stall was a rectangular area of coal to be extracted, which the buttyman regarded as his ‘place’. Sometimes this ‘place’ was shared with one or two partners or butties. The rate the buttyman was paid for each ton of coal extracted was negotiated with the colliery owner locally by the individual buttyman, sometimes with the support of the FDMA. The rate was dependent on the conditions at the face, the width and quality of the seam, systems of working and other factors such as faulting, the condition of the roof or floor, water, etc.[3] Coal extracted by the hewing team was sent to the pit head in marked drams, where they were weighed and the tonnage recorded. The buttymen were often also responsible for timbering and opening roadways and when they were also paid piece rates for work under a contract system.[4] According to Fisher, the nineteenth-century buttyman in the Forest:

had to be something of an entrepreneur within the pit. While the principal source of his earnings was the cutting of coal to be sent out of the pit for sale, there were other jobs to be done. The pit had to be developed, that is, roads had to be driven out through the bulk of the coal so that working places might be turned away, and when the pit worked more than one seam, or where a seam had been broken or displaced by a geological fault, smaller pits or drifts had to be made within the mine. If pillars had been extracted, the space left, the goaf, had to be packed with stone or timber supports; and perhaps stone or timber left in earlier work had to be shifted so as to direct roof pressures away from roadways or working places.

As the coal industry developed and tasks were divided up, the division of labour increased. Consequently, by the 1920s, only about 40 per cent of the total workforce worked on the coal face. While men involved in timbering and creating roadways were also paid piece rates, many other tasks in the pits were carried out by men or boys employed directly by the owners. They were paid a day rate and were often referred to as the company men. These included the surface workers and labourers, the craftsmen such as banksmen, enginemen, blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, pump men, and supervisors such as deputies and overmen. [5] Also included were men and boys involved with the haulage of coal, maintenance of haulage roads, clearing roof falls, and attending to ventilation.[6] In some circumstances, such as when the contract rate for a seam had yet to be agreed, the buttymen would work for an agreed day rate. However, in most cases, the employers preferred the piece rate system because it provided an incentive without the need for micro-management.

Contract Teams

The butty system was not unique to the Forest, but there were differences between districts on how the earnings were shared out within the teams working on the contract, depending on local custom and practice. How this was organised varied considerably from district to district, and there was a spectrum of systems, some more egalitarian than others. Stephanie Tailby has identified three distinctive butty arrangements: [7]

- The big butty system, whereby colliery owners sublet the working of an entire pit or districts of a pit to a contractor or partnership of contractors.

- The little butty system, whereby contracting colliers undertook to work a section of the coalface or a seam at piece rates and paid and supervised a small team of men and boys.

- An arrangement in which a collier or a pair of colliers working on piecework rates employed a day wage assistant, apprentice or boy.

In some districts, such as the Midlands, a single contractor or buttyman might employ many day men working a whole seam and he was viewed by the rest of the miners as very much part of the management hierarchy. This system was imported from the Midlands into the Kent coalfield in the 1920s and survived until the late 1930s.

Barry Johnson’s study of the Nottingham coalfield (Who Dips in the Tin? The Butty System in the Nottinghamshire Coalfield) and Robert Goffee’s study of the Kent coalfield (Incorporation and Conflict: A Case Study of Subcontracting in the Coal Industry) illustrate how the hierarchy and inequalities created by the butty system of working impacted on trade unionism by fragmenting the labour force and undermining solidarity.[8]

However, in some contract systems, the earnings were shared equally among all the men in the contract. Dave Douglass’s study of the Durham Pitman has revealed how a unique and more democratic form of organisation within the contract system (maras system) in the Durham coalfield created a strong sense of group solidarity and equality within small working groups.[9] The Durham miners operated a cavilling system where places were allocated afresh by drawing lots every quarter so that the more productive areas were shared equally.[10]

The puffler system in Yorkshire was similar to the little butty system, but by the 1940s, the system had changed so that the leader of the working group was paid an extra allowance by the colliery company rather than profits.[11]

It was common practice in most districts for colliers to employ boys. In South Wales, a pair of colliers might employ just one boy. It is unlikely that, even in the most equitable systems, the boys were paid as much as the men, and it is possible there were differentials depending on age and experience among the daymen.

CHAPTER TWO

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

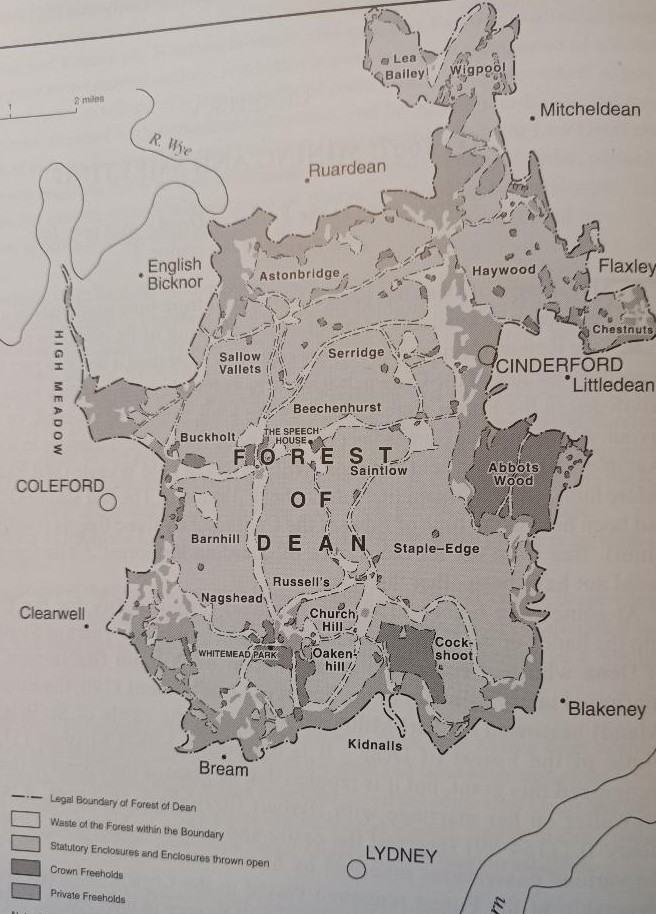

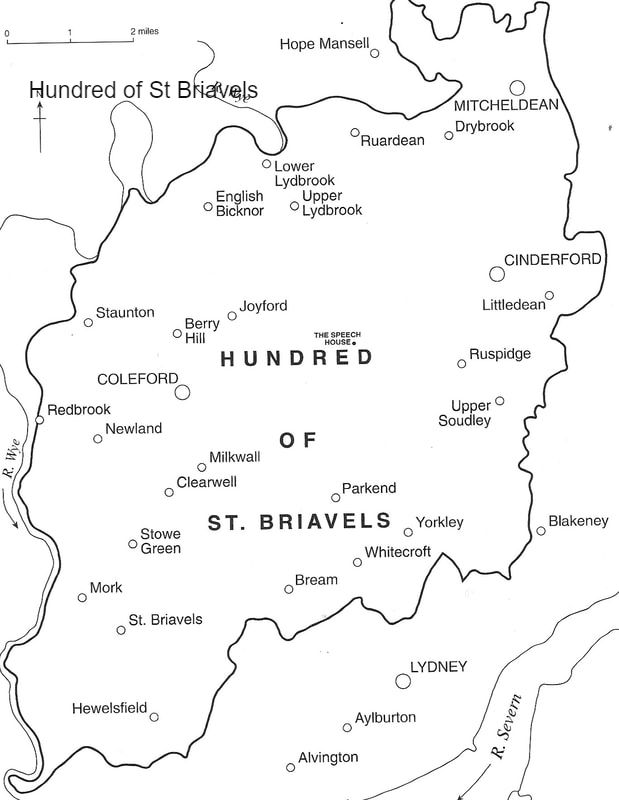

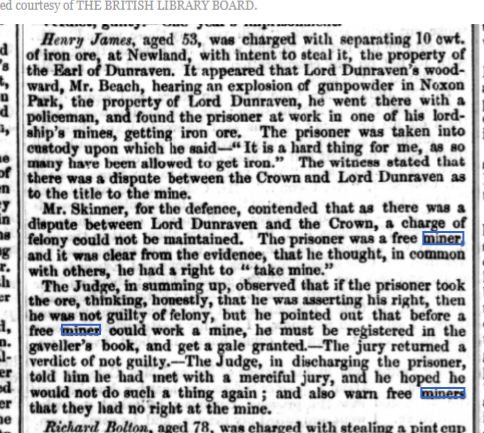

Coal and iron ore had been mined in the Forest of Dean for many centuries and as a result, a community of free miners had emerged who claimed certain rights and privileges. Free mining rights were claimed from ‘time immemorial’ by any son of a free miner born in the Forest of Dean who had worked a year and a day in a Forest pit. This allowed any free miner the exclusive right to open a pit anywhere in the statutory Forest of Dean, provided they paid royalties to the Crown, the owner of the land.[12]

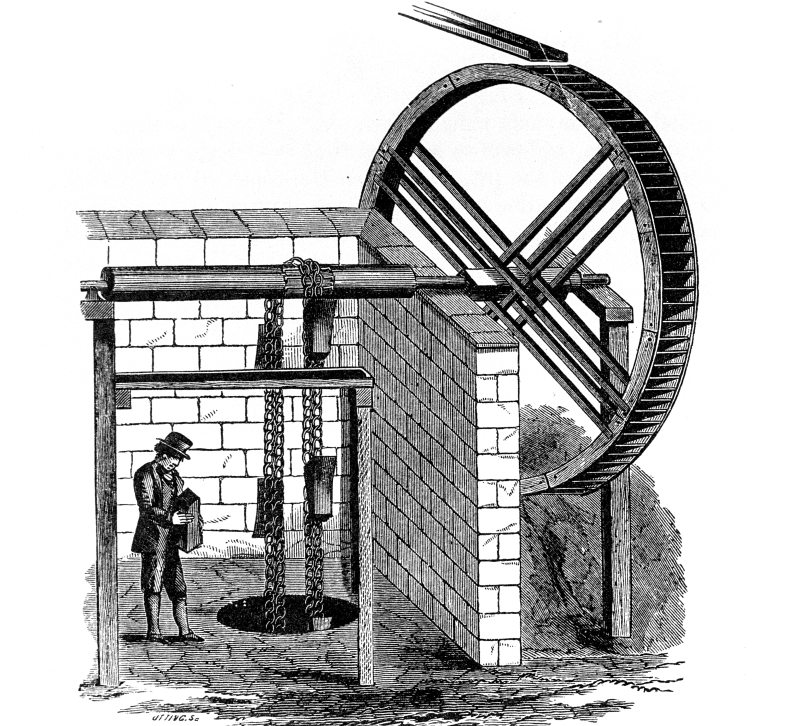

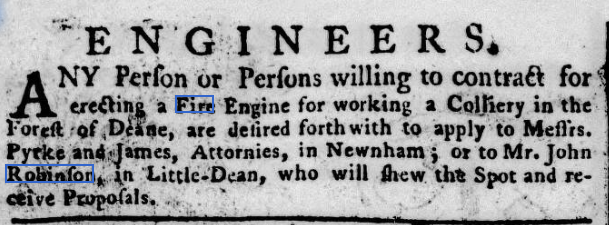

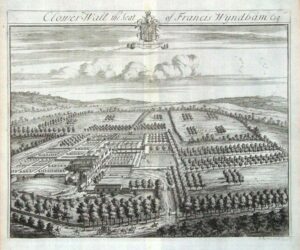

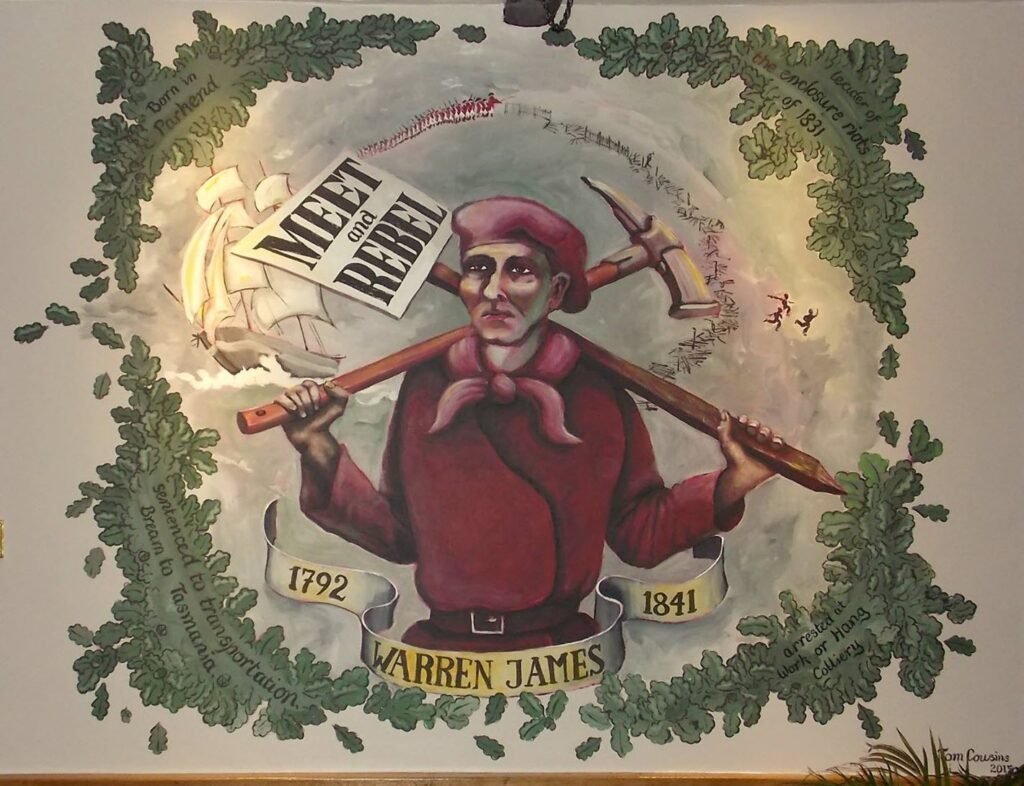

The early nineteenth century saw the penetration of, and transformation of, the old free-mining coal industry by capitalists from beyond the borders of the Forest. Men like Edward Protheroe, who made his money from his slave plantations in the Caribbean, invested in deep mining in the Forest of Dean, usually in partnership with a few enterprising and ambitious free miners.

As a result, in the years between 1790 and 1830 the mining industry in the Forest of Dean had passed, in the main, from the hands of a relatively large group of working proprietors of small-scale co-operative free mines into those of a small group of men, mostly outside capitalists, who had the capital to invest in steam engines, deep mining, railroads and iron furnaces.

However, their presence was opposed by most free miners who could not compete with the new deep mines, forcing many into unemployment and poverty. This was one of the main causes of the 1831 riot when the Foresters destroyed the Crown enclosures, which had restricted their customary free mining and grazing rights.[13] It was no coincidence that during the riot, Foresters specifically targeted Protheroe’s property.[14] After the 1831 uprising, the leaders were transported or imprisoned and many were forced to rebuild the enclosures.

The government responded by introducing limited free mining rights, set out in the Dean Forest (Mines) Act 1838, which guaranteed that only free miners could be awarded gales.[15] However, their rights were curtailed because the condition that free mining rights could only be claimed by the son of a free miner was removed. Free miners could now sell or lease their pits to whom they liked, and the Act confirmed the right of outsiders, including wealthy capitalists, to buy, own and sell mines. While a few free miners went into partnership with the capitalists, most of the inhabitants of the Forest were now dependent on the money they earned from wages or as contractors working in the new deep pits owned by the capitalists.[16]

Fisher argues that the significance of this was that property rights were introduced to mines, which displaced the egalitarian community of free miners with their strongly held beliefs in customary rights. The ownership and the use of resources in the Forest had been fundamentally transformed in ways which favoured private property, the exchange of commodities for profit and capital accumulation for a few at the expense of the labouring many.[17]

Fisher contends that the development of the butty system in the nineteenth century in the Forest had its roots in its tradition of free mining. He argues that the butty system allowed some colliers to retain some independence as small working masters and skilled artisans, while others were reduced to wage labourers.[18]

The Emergence of the Butty System

The capitalists had little knowledge or experience of mining. Protheroe had made his money from slavery, lived in Bristol and had no practical skills.[19] However, by 1832, he held financial interests in thirty-two coal mines in the Forest and was negotiating for others.

As the new owners expanded their pits and the workings grew more extensive, there was a growing demand for skilled hewers to extract the coal. The free miners, with their expertise and deep knowledge of the Forest coalfield, were the only ones equipped to meet this need. Requiring minimal training, they provided the colliery owners with a convenient source of highly skilled labour. These free miners were soon taken on as subcontractors, or buttymen, negotiating agreements with the owners to mine coal at fixed rates per ton. The buttymen were also able to hire labour as required from within their own community. Many free miners who continued operating their small pits found it increasingly difficult to compete with the larger, more modern enterprises.

However, those working as contractors for the new colliery owners could sometimes earn more and have a regular income. Free miners had become accustomed to a degree of independence, and the butty system allowed them to continue to work with a considerable amount of autonomy, hewing coal in small teams. As a result, they could continue to work unsupervised as small working masters, employing local labourers as required. However, the men and boys they employed, some of whom were ex-free miners, were reduced to wage labourers and dependent on the buttymen for work. The old free mining community had become fractured between the buttymen and their employees

The system allowed the buttymen to define the social relations of work and exert high levels of control over the labour process, backed up by a strong commitment to custom and practice. However, it is unclear to what degree the buttymen were reproducing pre-existing social relations. The average number of miners who had been working in a free mine around 1800 was four, usually including a boy.[20] Free miners worked in partnerships, called verns, often made up of family and friends, but may have also employed one or two casual labourers, an arrangement which was often used by the buttymen.

Most buttymen worked on the job, on the face, often with fathers, sons and brothers as daymen or partners. The buttymen supplied their own tools and timber. They had to face many challenges that could lead to loss of earnings, such as opening and clearing up stalls, dealing with broken or displaced seams, coping with water and soft roofs, and the occurrence of stone. These were often referred to as ‘abnormal places’. If no coal was produced, they earned no money but still had to pay their daymen and boys. Sometimes they had to ask the colliery owners for an allowance to cover such circumstances. In addition, they could be subject to victimisation by the owners and be given difficult working conditions.

The contradiction in the butty system for the local community is clear: some Foresters could maintain some form of dignity and respect working as buttymen, but the rest became part of a casual labour force, subject to the whims of the market, the coal owners and the contractors. This is how Fisher explains the system:

Work in the large pits, from the early 1820s, came to be organised around contract miners, or buttymen. The masters employed some men on day wages, in order to maintain travelling and haulage roads in the pit, but most of those whose pay came directly from the master were contract men. A man and his mate (the butties) undertook to work a stall. That is, they agreed to hew the coal and load it into tubs, for which they received a stipulated rate per ton (the contract). The butties then employed men and boys at a fixed rate per day (the daymen) to help with the work. The butty paid his daymen rates which varied according to his assessment of their value as workmen. That depended in part on their age and experience. The daymen included experienced, adult colliers who worked at the coal face, and boys and youths in various stages of learning the craft, for the “off hand” work of loading, moving materials, cutting and setting timber, and hauling tubs from the face to the main transport roads. The number of daymen in each stall varied according to the needs of the butties, but there were not many of them: perhaps there was a ratio of two butties to four or five daymen.

Free mining continued, but by the mid-nineteenth century, the output of the free mines was small compared to the deep pits, although free mining remained an important part of Forest identity and culture.

In the mid-nineteenth century, about two-thirds of Forest coal went to the house coal trade throughout southwestern England, with the main demand in the winter and one-fifth went to the local iron industry. So, the buttyman’s power to hire and fire according to the demand for coal was important. This meant the daymen needed to have other jobs and often worked on farms in the summer. Therefore, their economic situation was based on both dependency and uncertainty, just like any other casual labour force. However, many of the younger daymen aspired to be a buttyman and treated their apprenticeship with the buttyman as an opportunity to learn the trade.

The owners, on the other hand, took little risk but had a guaranteed profit from the coal produced. They had no employment obligations, with no hiring and firing of labourers and did not need to micro-manage the workforce. Coal mine managers as a professional class did not exist in the nineteenth century.

Truck System

In 1870, a government commission was appointed to discover if the truck system was still operating in the British coalfields, in disregard of the Acts of Parliament prohibiting such a system. In the truck system, employers paid part or all the wages in the form of credit notes, which could then only be exchanged in the employer’s shops or pubs. During the investigation, it became clear that in some cases in the Forest of Dean, butties and mine owners were paying their men using credit notes for shops and pubs, some of which were owned by themselves or family members, and also paying their men in pubs they owned or managed.[21] In 1886, Thomas Hale, a buttyman who worked in iron mines owned by the Crawshays, wrote in his diary:

When I was a lad working in the coal pits, the butties used to take us to some public house and cause us to spend some of our money that one had worked very hard for.[22]

Fisher characterised the nineteenth-century Forest of Dean contractors as ‘little buttymen’ because he argued that they only employed a small number of men and boys.[23] However, the newspaper reports about the Commission reveal that in some pits the butties at Lightmoor, Trafalgar and Foxes Bridge were employing up to 70 men. This meant that in some cases in the 1870s in the Forest of Dean, the buttymen were in control of whole seams or sections of the mine as they were in Nottingham and Derbyshire. In terms of social relations, there was a significant difference between these contractors and the little buttymen who may only employ one or two labourers. The term butty system must, therefore, be used with considerable caution as its meaning varied from district to district, pit to pit and seam to seam and changed over time.

Examples of the Ratio of Large Buttymen to Daymen in 1870[24]

| Buttyman | Colliery | No of Daymen | Proprieter |

| James Braidnack | Foxes Bridge | 40 | Shop |

| John Hamlyn | Lightmoor | 70 | Shop and Pub |

| John Emery | Lightmoor | 70 | Shop and Pub |

| William Bevan | Lightmoor | 10 | Pub |

| James Griffiths | Duck Pit | 10 | |

| George Herbert | Trafalgar | 40 |

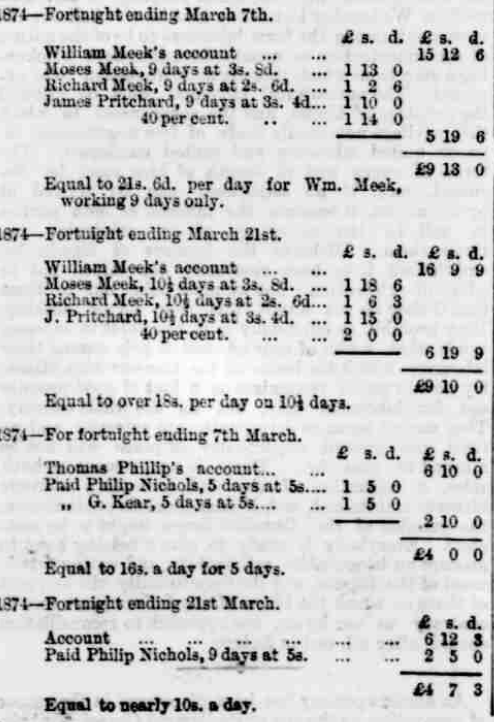

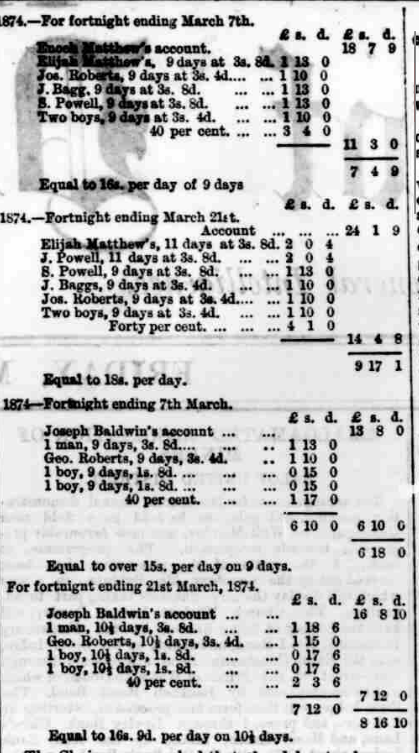

Examples of Ratio of Little Buttymen to Daymen in 1874[25]

| Buttyman | No. of Daymen | |

| William Meek | 3 including 2 Meeks | |

| Thomas Phillips | 2 | |

| Elijah Matthews | 2-4 plus 2 boys | |

| Joseph Baldwin | 2 plus 2 boys | |

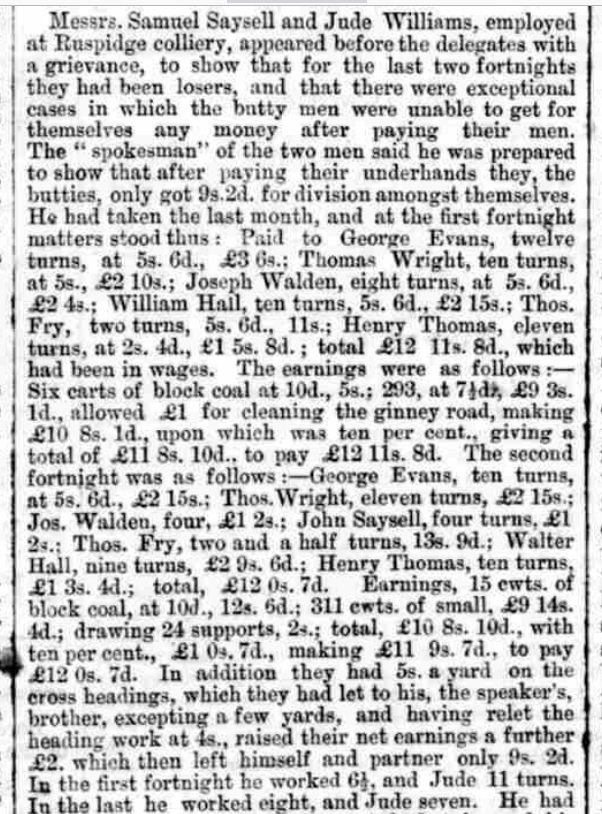

| Samuel Saysell and Jude Williams | 5 plus 1 boy | |

| Shellah Russell and Joseph Burrris | 4 |

Trade unionism

The butty system created divisions within the workforce, which impacted the development of trade unionism and its relationship with the colliery owners. The divisions were not only between the buttymen and their daymen but also between the buttymen themselves as they competed for the best workplaces or stalls. This could lead to victimisation or favouritism because some stalls were more difficult to work than others due to water, faults, soft roofs, etc. At the same time, the buttymen were aware that an experienced day man could always step in to take their place during a dispute with the owners. Since the butty system undermined union organisation, it was opposed by the Miners’ National Union (MNU) led by Alexander Macdonald. In November 1866, the Gloucester Journal reported that:

At Wednesday’s meeting of the Miners Conference now sitting in Nottingham, the butty system came under review and was universally condemned. One of the speakers characterised it as the worst evil under which the miner suffered, and another as the root of most of the miners’ grievances. The views of the Conference on the subject are to be embodied in their petition to parliament..[26]

William Morgan, a butty, raised the question of divisions among the men at a meeting in Cinderford Town Hall in October 1871. He complained of how the masters might set the men against one another and argued that there is no other way open to us than to have a union and stick together.[27]

Timothy Mountjoy (July 1871-1878)

There were no recognised miners’ trade unions in the Forest of Dean before 1871. Before this, the buttymen negotiated their contract rates either individually or collectively at each pit. A typical rate paid to the buttymen in 1870 was 1s 6d a ton, with a pit head price for the colliery owners of 10s a ton. The rate varied from pit to pit, seam to seam. However, there was competition between the buttymen and this could lead to undercutting. There were also many disputes about how the coal was weighed at the pit head and this led to to a breakdown in trust between the owners and the buttymen.

At this time, most agreements between the buttymen and the colliery owners were based on an informal sliding scale in which a percentage was added or deducted from contract rates as the price of coal went up and down. The sliding scale assumed that there was an identity of interest between capital and labour and wages were subject to the anarchy of the coal market.

An example of an informal agreement could be as follows: If the pit head price of coal is 10s a ton and the negotiated contract rate between butty and master was 1s 6d a ton, then an increase in the price of coal of 1s could give a 5% increase in the contract rate, giving a new contract rate of 1s 7d per ton. These agreements were often ad hoc and varied from pit to pit and contract to contract. However, the colliery owners often did not abide by agreements and rarely voluntarily increased wages.

In the early 1870s, the rising price of coal led to a strong demand for labour, which empowered the miners to try and push up the contract rates. The owners refused their demands and so in July 1871, a strike of 800 men and boys at Trafalgar colliery, followed two months later by a strike of 600 men at the Parkend Coal Company, resulted in increased wages.[28]

The strikes were led by buttymen but involved the whole workforce. Six trade union lodges were formed, representing the main large pits and the men organised themselves into the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association (FDMA).[29] They elected a council made up of representatives from each lodge.[30] They then recruited a popular local miner and preacher, Timothy Mountjoy, as their full-time paid worker.[31] The FDMA then affiliated with the national miners’ union, the Amalgamated Association of Miners (AAM), which had the resources to pay strike pay.[32] There is no evidence that the larger buttymen mentioned above were elected to the council, as they would have been viewed as very much part of the colliery management.

The price of coal continued to rise, reaching 20s for the best Forest block coal by the summer of 1873. As a result, the FDMA successfully pushed contract rates up by 40 per cent above those of 1871.[33]

The buttymen also gained the right to appoint their own checkweighmen, which was sanctioned by the Mines Act of 1872, to verify the findings of the colliery owner’s weighman on the tonnage of coal produced by each hewing team. The checkweighman needed to have good literacy and numeracy skills and often became the lodge representative in negotiations with the owners. The FDMA insisted that calibrated weighing machines be installed at the pit banks. Fisher argues that in the nineteenth century:

Elected by the butties and paid by them, the checkweighman was perhaps the only person in the pit who was capable of maintaining independent action, of surviving moments of vindictiveness on the part of the master. The checkweighman, therefore, became the focus of lodge organisation, keeping the books, calling and chairing meetings and leading deputations..

The FDMA also obtained an agreement to reduce winding hours from ten to eight and that wages be paid every two weeks.[34] By 1873, the FDMA had recruited 4,500 members, or about eighty per cent of the total number of colliers in the district. including the buttymen, day men and company men.

However, there was still no guaranteed rate for the day men whose pay remained dependent on their level of skill, age, value in the labour market and whim of the buttyman. There was also no guaranteed work, as some daymen may only be offered one or two days of work a week, while others could get 5 or 6 days a week. The FDMA Council initially accepted that it was up to the buttyman to determine when and where the day men could work and what wage he paid his men. Sometimes percentage increases were not passed on and daymen could easily be victimised or sacked.[35]

The approximate market wage for a skilled day man in September 1873 was based on the rate for 1871, which was 3s 4d per shift. However, in most pits, the buttymen were very aware that they had to keep daymen on their side and so, in most cases, increased wages if there was an increase in contract rates. This meant that, by the summer of 1873, most of the skilled daymen were now earning the 1870 day rate (approximately 3s 4d) plus 40%, giving 4s 8d, but their labourers and boys earned less.[36] In contrast, the company men, such as banksmen and surface men, were paid approximately 2s 8d plus forty per cent.

Despite this, there was conflict when it became apparent that some of the buttymen at Trafalgar did not pass on the advance to their day men. In response, the FDMA passed a resolution that all advances should be passed on to the day men. The FDMA Executive Council went further and suggested 6s plus 40 per cent for skilled daymen. This led to a flurry of letters in the Forest of Dean Examiner.

Some miners argued that some of the day men were every bit as skilled as the buttymen and so should be awarded a good rate if they worked hard. Others argued that some daymen were “clod hoppers recently come from the plough tail” and “the public house slashers” and should not be paid the same as those with skills. One day rate collier argued:

I am one of those who believe the time has come when the ordinary collier should speak plainly out, objecting to the present unsatisfactory method of paying the daymen. I venture to say that every day collier able to do a fair eight hours’ work ought to have the same uniform standard wages, together with his 40 per cent. Having in general terms explained the grievance of our day-men or at least many of them—l would affirm that in the Rocky vein, where I am a day collier, there are some butties who out of every five per cent, pay their men at a reduced rate, instead of what is fair, just, and honourable.

Some skilled day men accepted that the experienced buttymen should earn more, while others insisted on higher pay. The demand for skilled daymen was high and so some could negotiate higher rates of pay. Some others were able to negotiate with the owners for their own stalls and became buttymen themselves. In the end, the FDMA decided to leave it to the buttymen to choose how much they wanted to pay their daymen according to their market value.

Average Earnings per shift for Little Buttymen in September 1873 (2s a ton for cutting coal)[37]

| Buttyman | Earnings per shift |

| James Johnson | 10s 8d |

| Davis | 9s 3d |

| Edwards | 13s 2d |

| John Tingle | 12s 1d |

| Charles Smith | 7s 8d |

However, the buttymen sometimes earned little for themselves or even made a loss. For instance, in December 1874, it was reported in the Forest of Dean Examiner that Samuel Saysell and Jude Williams had no money left over after paying their 5 daymen 5s 6d a shift and their one boy 2s 4d a shift.

Lock Out

In 1873, the colliery owners responded to the formation of the FDMA and formed the Forest of Dean Coal Mine Owners Association. However, in the summer of 1874, the price of coal fell and the owners announced they would cut the rates by 10%. In the autumn, the owners attempted to impose another 10% reduction, but the FDMA refused to accept the wage cut and challenged the owners’ figures on the selling price of coal and the amount wages had increased during the boom. The owners refused to negotiate with the FDMA, characterising Mountjoy and district officers as inflammatory agitators. The miners refused to work for the new rates and so were locked out of their pits

After 10 weeks, the owners struck a deal with the AAM national officers, who were concerned about the mounting cost of the strike, while Mountjoy and his fellow officers were locked out of the talks. The agreement accepted the 10% reduction and the men reluctantly returned to work in February 1875 after struggling to survive through one of the coldest winters for a generation. The owners imposed another two cuts in tonnage rates in July 1874. In response, the buttymen cut the rates paid to the day men and laid some off.

The owners continued to refuse to meet with Mountjoy and district officers and insisted that they would only negotiate directly with representatives of the buttymen from each pit. As a result, the power of the FDMA ebbed and the role of the individual lodges became more important.

Sliding Scale

In August 1875, a formal sliding scale to govern the movement of hewing rates of pay in relation to coal prices was agreed between buttymen and the colliery owners at a meeting at Littledean. A percentage was added or deducted from this figure depending on the selling price of the coal. The agreement was based on a price of twelve shillings per ton at the pit mouth for the best-screened block. The buttymen’s tonnage rates were agreed at 15% over the base rates of 1871. From that base, rates were to move five per cent for every movement of one shilling in prices. There was no provision for the day men, who were left by default to the kindness or not of the buttymen.

Since the colliery owners continued to refuse to meet with Mountjoy and the FDMA officials and wages were determined by the sliding scale, there was no role for the FDMA. Any negotiations were carried out by deputations made up of the buttymen or checkweighmen from the individual pits.

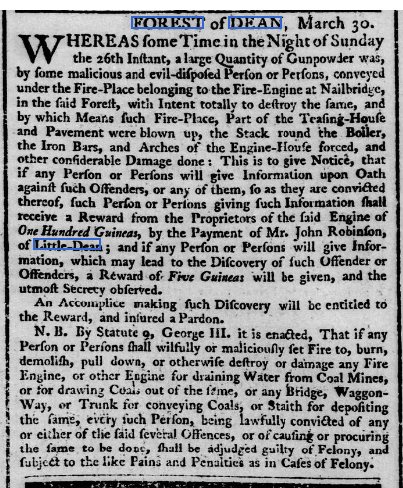

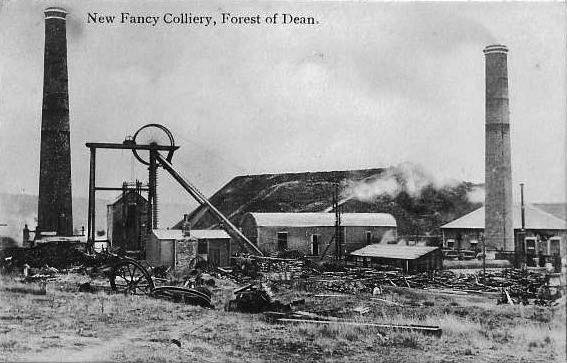

In February 1877, the owners imposed another ten per cent reduction, and 3000 miners refused to work. In one case, desperate strikers fired a gun at enginemen at Trafalgar colliery who had returned to work during the strike to operate the pumps to prevent the mine flooding.[40] In another case, John Harris from Harry Hill, who had returned to work, had his house blown up with dynamite, and soon after, John Trigg from Bream, who had returned to work at New Fancy colliery, was badly beaten up.[41] The owners still refused to meet with Mountjoy and members of the FDMA Council. Consequently, a deputation made up of delegates from each pit was forced by the owners to accept the ten per cent reduction.[42]

During 1877 and 1878, the price of coal and wages continued to fall partly because of price competition amongst the owners.[38] This situation hit the day men particularly hard as many were forced into short-term work or unemployment. Some unemployed day men were granted poor law relief, provided they accepted unpaid work breaking stones in local quarries.[39]

Soon, the level of wages was reduced to that of 1871, the membership of the FDMA had collapsed and there was no money to continue to pay Mountjoy. The owners became law unto themselves and no longer abided by the Littledean agreement.[43] For example, in September 1879, the owners of New Fancy Colliery imposed another ten per cent reduction on the rate per ton. With no district organisation, the buttymen reluctantly accepted the reduction and imposed a ten per cent cut in the wages on the day men, which gave them just 3s a day. The day men refused to accept this and went on strike, but with no district union, they were forced to accept the reduction and returned to work, defeated, one week later.

Neddy Rymer (1882 -1886)

In 1882, confidence among the workforce returned as the price of coal began to rise. A group of miners, led by the checkweighman John Ennis, decided to rebuild the FDMA and recruited a new agent, Neddy Rymer.

I hope that none will take offence,

And think I’m but a charmer,

For everybody knows I am

Miner and Workman’s Advocate 17 May 1865[44]

Rymer had been involved in mining union activism since the 1860s and worked in most of the coalfields in northern England, where he had gained a reputation as a militant arguing against the sliding scale and alternatively arguing for a living wage which was independent of the price of coal.[45] In 1873, he said:

Whatever be the price of coal or iron, or whatever be the state of trade in the money market, we must have our position made secure and our labour protected from the wolves and vultures of a mean, selfish, and brutal generation.[46]

This meant that in 1873, he was against the use of a sliding scale. However, by the late 1870s, he had moderated his views after the depression in the coal trade led to defeats in coalfields across the country. Consequently, when he was recruited as the new FDMA agent in 1882, he argued that his first task would be to negotiate a sliding scale and a board of conciliation with the owners.

A meeting in Cinderford on Saturday 14 October 1882, attended by Rymer, Mountjoy and national officers, formally announced the formation of the new organisation and agreed to demand a ten per cent pay rise.[47] By the end of the month, the FDMA had accepted a 5 per cent offer from the employers on condition that they agreed to the establishment of a sliding scale.[48]

In his first two months in the Forest, Rymer was successful in building up the FDMA with 1000 members, including buttymen, daymen and company men. Soon, about 30 pit lodges had been formed and sent delegates to the new FDMA Council, which affiliated with the AAM. At the end of November, the FDMA presented four demands to the owners:

- Another increase in wages of 5 per cent.

- Buttymen should receive a tonnage remuneration for work in abnormal places.

- The formation of a sliding scale based on company accounts and a board of conciliation.[49]

However, initially, the owners would only accept the demand for a conciliation board.[50] In addition, the FDMA Council, now representing the daymen as well as the buttymen, demanded:

- The election of checkweighmen by all the workmen, including the daymen.

- The day men should be paid weekly.

- An eight-hour day including trammers.[51]

- Day men should not be paid in pubs, particularly if they were owned by a buttyman.

All these demands were controversial. The checkweighmen had traditionally been voted into office by the buttymen to whom they felt responsible, rather than by all the colliers of whatever status.

The issue of weekly pay was contentious because it would mean that the owners and the buttymen would need to agree on details of work done every week, including measuring up the yardage for timbering and road ripping, as well as the total tonnage of coal mined.

The buttymen often expected the trammers, who were employed by the buttymen, to clear coal from the face to the pit head and get it weighed in after they had left work in preparation for the next day’s work. This meant they were expected to work more than eight hours. In fact, there were cases of the buttymen employing children unsupervised on the night shift to move coal mined during the day. At a meeting in September 1973, Mountjoy reported that:

at Crump Meadow there were two butty men who holed theft coal in the day and prepared it, and at night sent their two lads to hod it into the roads, and another to fill it. There were these little boys away down in the pits, perhaps 150 yards from any living creature.[52]

The day men had traditionally been paid in pubs, some of which were owned by buttymen or their relations.

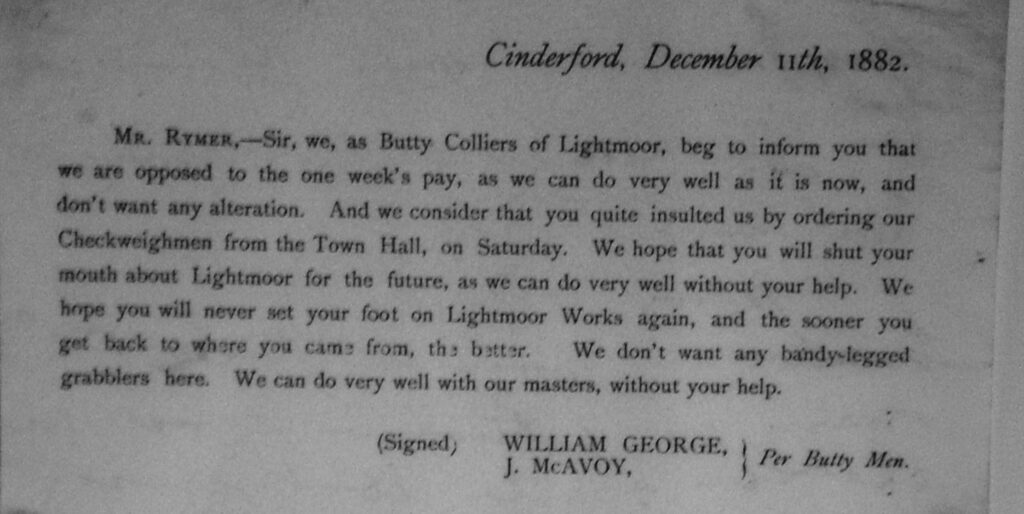

As a result, the FDMA Executive immediately ran into conflict with some of the more powerful Lightmoor and Trafalgar butties and their checkweighmen over these four demands. Things came to a head at a meeting in Cinderford on Saturday 2 December 1882, when an argument erupted and two checkweighmen from Lightmoor were ejected from the meeting.[53] Consequently, the two checkweighmen involved, William George and John MacAvoy, wrote a letter to the FDMA Council.

Cinderford, December 11th 1882.

Mr Rymer, Sir, – we, as Butty Colliers of Lightmoor, beg to inform you that we are opposed to the one week’s pay, as we can do very well as it is now, and don’t want any alteration. And we consider that you quite insulted us by ordering our Checkweighmen from the Town Hall, on Saturday, We hope that you will shut your mouth about Lightmoor for the future, as we can do very well without your help. We hope you will never set your foot on Lightmoor Works again, and the sooner you get back to where you came from the better. We don’t want any bandy-legged grabbers here. We can do very well with our masters, without your help.

(Signed WILLIAM GEORGE and J McAvoy ) per Buttymen.

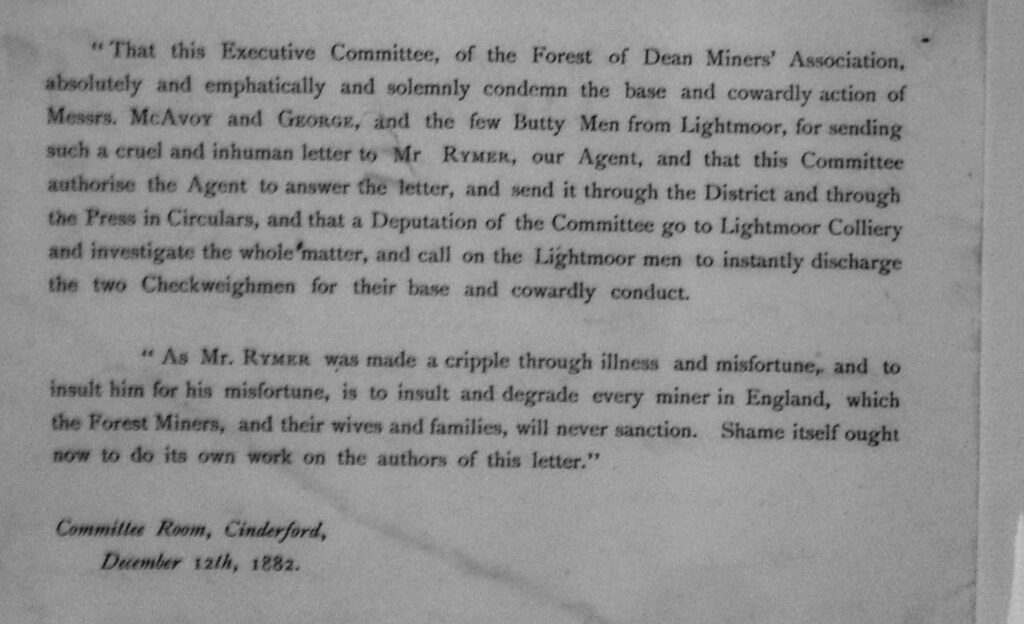

The next day, the FDMA Executive Committee met and drafted the following reply, which was circulated to all those concerned.

That this Executive, Committee, of the Forest of Dean Miners’ Association, absolutely and emphatically and solemnly condemn the base and cowardly action of Messrs. MacAvoy and George, and the few Butty Men from Lightmoor, for sending such a cruel and inhuman letter to Mr Rymer, our Agent, and that this Committee authorise the Agent to answer the letter, and send it through the District and through the Press in Circulars, and that a Deputation of the Committee go to Lightmoor Colliery and investigate the whole matter, and call on the Lightmoor men to instantly discharge the two Checkweighmen for their base and cowardly conduct.

As Mr. Rymer was made a cripple through illness and misfortune, and to insult him for his misfortune, is to insult and degrade every miner in England, which the Forest Miners, and their wives and families, will never sanction. Shame itself ought now do its own work on the authors of this letter.

Committee Room, Cinderford, December 12th 1882.

However, by now, the membership had reached about 3,000, three-quarters of the miners in the Forest of Dean.[54] Rymer had built up a hardcore of loyal supporters among the day men and some of the smaller buttymen, including the chair of the FDMA Council checkweighman, John Ennis. At a meeting between the owners and the FDMA representatives on Monday 18 December, the owners conceded a 5 per cent rise in contract rates. Rymer also attended a national conference in Leeds with a mandate from the FDMA to support a motion for the regulation of the output of coal by working only eight hours a day.[55]

Living Wage

By March 1883, a depression had returned to the coal trade, and as a result, the colliery owners proposed a 10 per cent reduction in wages. Rymer argued that the men should be paid a living wage independent of the price of coal, which meant a rejection of the sliding scale. He argued that it is not the miners’ responsibility that competition between owners forces down wages. He added that the FDMA should reject arbitration based on coal prices but accept arbitration on the establishment of a minimum wage, which would force the price of coal upwards.

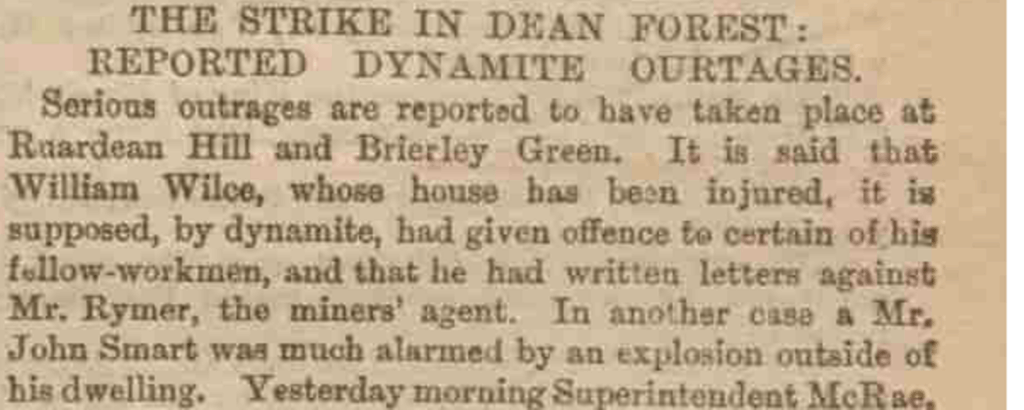

Consequently, the men refused to accept the reduction and so were locked out. As with Mountjoy, the colliery owners refused to talk to Rymer and the FDMA District Officers. This attempt by the owners to undermine the union again caused considerable bitterness and conflict within the local community. On one hand, some of the larger buttymen from Lightmoor and Trafalgar Colliery returned to work on the owners’ terms and attacked Rymer in the local press. On the other hand, some of the smaller buttymen and daymen stayed out on strike. Some were driven to acts of violence. such as the dynamiting of the house of William Wilce, who was a checkweighman at Trafalgar Colliery. In addition, the house of John Smart, who had returned to work at Trafalgar, had its window broken.[56]

The following words were posted on the walls outside Lightmoor Colliery:

Blood! Blood! Blood! If you go into work you had better make your wills.[57]

However, after five weeks and the intervention of national officers, the men returned to work with a 5 per cent reduction, with the other 5 per cent referred to arbitration. In the end, they agreed on a total of a 7.5% reduction. Rymer felt betrayed by the national union and maintained his position that miners should be paid a living wage, whatever the price of coal:

The miner seeks….. to claim from the country a fair reward for his labours and, as the country employs her wealth, and possesses her power and influence through the manhood, skill and labour of the workman, he sees no reason why he ought to toil and live in poverty……This the miner sees, and determines not to allow his blood and life to be bartered away like dead metal, or as though he were a mere chattel. [58]

However, as before, the power of the FDMA was undermined by the tactics of the owners, the sliding scale and the existence of the butty system, which created divisions in the workforce. Rymer struggled on to keep the FDMA alive and was forced to accept a sliding-scale agreement to run to 1884. The scale was based on a pithead selling price of 9s a ton, with the buttymen receiving 2.5% above the 1871 contract rate. This was accepted by the buttymen but ignored the plight of day men who were left again with no agreement on wages.

Rymer continued to campaign for weekly pay and the end to the payment of the men in pubs, but without success. However, he successfully campaigned for timber to be provided by the owners, obtained an agreement that the existing custom of 21 cwt in a ton of coal be reduced to 20 cwt in a ton and was instrumental in getting a Liberal MP elected in the constituency.

However, after the strike, he lost his authority because the colliery owners refused to negotiate with him while the senior buttymen accepted the establishment of a sliding scale. The re-signing of the agreement in 1885 and 1886 effectively made the district union and the agent redundant. By June 1886, there were not sufficient funds in the union to pay his wages and he was asked to resign. Fisher argues:

Our understanding of colliers’ unionism, at least in the Forest of Dean, is modified if conventional assumptions about the traditional social cohesion of the colliers are abandoned and the divisions of the labour process are taken into account. The union is seen not to have been concerned in an even-handed way with the problems of all colliery workers. It was the buttymen who started the union in the first place. Their view of pit work governed the behaviour of the union, particularly in the key area of wage bargaining. The butty wanted a fair share of the fluctuating price of coal, but had no ambition to set a minimum rate or standard for his labour: as a small working master he accepted the fact of risk and its influence on his profits. Given a formal sliding scale which would distribute the price of coal equitably between master and butty, there was no reason for them to quarrel. The dayman was, in the union as in the working place, subordinate to the butty. The union made no attempt to abolish the dayman’s condition of dependency. For their part, the masters chose to deal with the buttymen through the nexus of the sliding scale.[59]

CHAPTER THREE

GEORGE ROWLINSON

In 1886, while travelling the country promoting a Liberal newspaper, The Labour Tribune, George Rowlinson visited the Forest of Dean and addressed at least ten meetings in the district promoting the paper and trade unionism. On the night before he was due to leave, he was approached by a group of checkweighmen led by John McAvoy and William George, who asked him if he would be willing to take on the role of agent of the FDMA. He accepted and for the next 32 years, Rowlinson worked closely with the checkweighmen and buttymen who dominated the FDMA Executive during his years in office.

Rowlinson was a man of moderate views and an advocate of the sliding scale and a cautious, market-conscious approach to dealings with the colliery owners. The senior buttymen and checkweighman had found someone who suited their needs. Fisher contrasts Rymer with Rowlinson in this way:

His first meeting was not for the purpose of denouncing the masters as tyrants and robbers of value which labour had created or to demand a wage increase. It was a tea meeting presided over by the Reverend W. Thomas, at which Rowlinson expounded his belief that the interests of masters and men were identical.[60]

Miners’ Federation of Great Britain

However, Rowlinson’s approach to industrial relations was at odds with developing militancy in the nation’s coalfield, which sought to break down regional isolation and led to the formation of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB).

The MFGB was established in 1888 to represent and coordinate the affairs of local and regional miners’ unions in England, Scotland and Wales while allowing the district associations, like the FDMA, to remain largely autonomous.

At the inaugural meeting, it was agreed to raise funds to campaign around wages and conditions and for an eight-hour day, secure legislation, and obtain compensation for miners killed in accidents. The MFGB was hostile to the sliding scale as it had failed to provide a living wage during the depressions in the coal trade.

The founding unions which formed the MFGB covered Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, North Wales and the Midland Counties, including the Forest of Dean, Bristol and Somerset. However, the exporting districts of South Wales, Northumberland and Durham initially refused to join and their leaders were strong advocates of the sliding scale. The MFGB’s membership increased by 30% in its first year, and by 1890, its member federations had 250,000 members.

1893 Strike

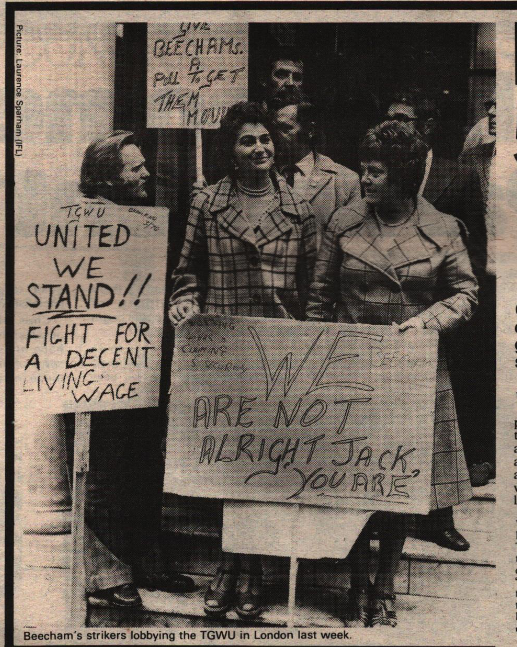

Just like in the early 1870s and 1880s, the MFGB and FDMA achieved some success on the back of a rising market in the coal trade in the early 1890s. However, when the price of coal fell in 1893 because of a depression in the coal trade, the coal mine owners threatened to reduce wages by 25%.

The miners in those areas that had joined the MFGB, including the Forest, refused to accept the reduction in wages, and at the end of July, miners in most pits in districts affiliated with the MFGB were locked out.[61] The fundamental issue behind the lockout was the use of the sliding scale, which had forced miners’ wages below the poverty level.

John MacAvoy, who was chairman of the FDMA, disagreed with the strike and resigned at the end of August. Then on 18 September, despite some local and national opposition, Rowlinson, with the support of some of the buttymen in the Forest, led the Forest miners back to work. Rowlinson negotiated a deal with the employers, resulting in a 20 per cent drop in wages and a return to a sliding scale agreement. However, the shortage of coal because of the strike led to a temporary increase in the price of coal, and so contract rates in the Forest rose. Rowlinson argued that his decision had been vindicated. However, the unilateral action resulted in the expulsion of the FDMA from the MFGB.

In the other regions, the strike continued and, after the use of troops to shoot dead striking miners in Yorkshire, the government intervened and encouraged the owners to agree upon a return to work with no cut in wages and no cuts to take place before 1 February 1894. In addition, it was agreed that wages in future would be determined by local Conciliation Boards, which would avoid drastic cuts in wages. This meant the formal sliding scale, which tied wages directly to the price of coal at the pit head, was abandoned. The miners returned to work on 17 November without having to concede any loss in pay. In the end, a 10% reduction in wages was agreed by the conciliation boards to start from July 1894.

The Conciliation Boards

The local Conciliation Boards were made up of an independent chairman, worker and owner representatives. Their main purpose was to resolve industrial disputes without resorting to lockouts, strikes and violence. In doing so, the Conciliation Boards were able to take other factors into account, such as inflation, cost of living, and capital investment and they attempted to avoid any severe reduction in wages.

The FDMA was able to take advantage of this agreement, and in February 1895, the FDMA reached an arrangement with the local coal mine owners to set up a local Conciliation Board. However, in the Forest, the FDMA continued to use a sliding scale, which was overseen by the Conciliation Board, which agreed a percentage increase or decrease in wages of 5 per cent in line with a one-shilling increase or decrease in the price of coal.

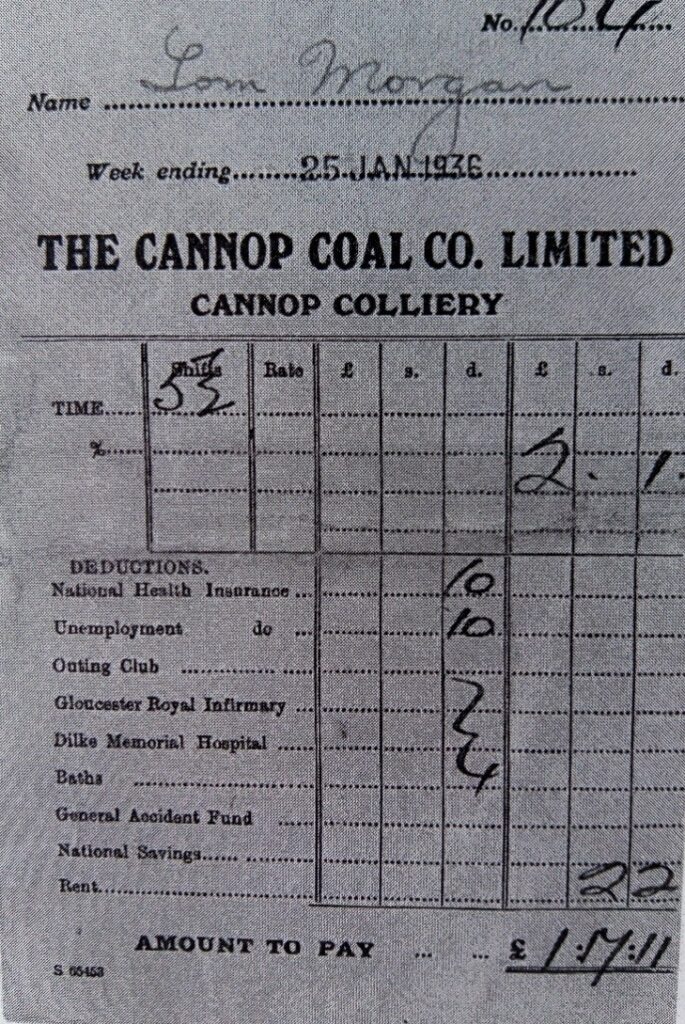

In the Forest, a base rate was set at the rate agreed in 1888 and applied to tonnage rates, rates for other tasks such as road ripping and timber work. Similarly, for those on a day wage and employed by the buttymen or the company, the base rate was the actual level of pay in 1888. However, since the base rate was set at different levels for different areas, pits and coal seams, the rates varied considerably depending on the conditions and local negotiations. In addition, new base rates would need to be negotiated between the miners and the mine owner for new seams or changes in conditions. The percentage above the base rate was agreed upon by the Conciliation Board and reviewed at regular intervals, depending mainly on the price of coal.[62]

In addition, in 1895, it was agreed that the maximum percentage above or below the base rate would be 60 per cent. In 1888, in the Forest of Dean, the day rate for hewers was 4s a shift. In 1898, the minimum day rate for hewers was 4s plus 15 per cent, giving a minimum wage of 4s 7d a shift. The buttymen, who were on piece rates, normally earned more than this and may have paid their skilled daymen a day rate above or below this wage. It was accepted practice that the buttymen would pay skilled daymen this rate, but there was no statutory obligation to do so.

Gradually, the other local associations joined the MFGB. In 1908, the Liberal government passed the Coal Mines Regulation Act, which limited the hours a miner could work to eight hours per day, which was one of the demands raised by Rymer in 1883.

In September 1909, a ballot of the FDMA members resulted in 93 per cent voting in favour of re-joining the MFGB. By then, John MacAvoy had obtained work as manager at Lightmoor Colliery and established a close relationship with the buttymen at the pit.

In October 1909, six buttymen came out in a dispute over the cutting of a pillar of coal at Flour Mill colliery. When the owners sacked the buttymen, the rest of the 700 men also came out on strike in support. As a result, the owners threatened to close the pit. However, the men returned to work after two weeks when concessions were made on both sides.

1912 National Miners’ Strike

The conflict over payment for working in abnormal places was one of the main factors leading to the 1912 National Miners’ Strike. In October 1911, an MFGB conference resolved:

to take immediate steps to secure an individual district minimum wage for all men and boys working in the mines . . . without any references to the places being abnormal.[63]

Individual districts prepared schedules of minimum rates for each of the various grades of labour. For instance, Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire asked for a top rate of 8s for hewers. In the end, the MFGB officially conceded to a demand of national rate of 7s. 6d. In a national ballot, over half the MFGB membership voted for strike action in support of their demand. In February 1912, after negotiations failed, a nationwide strike over the demand for a national minimum wage began. The strike involved one million workers and had the support of Forest of Dean miners who had voted 1,585 for the strike with 245 against. It was the biggest strike Britain had ever seen and for more than a month, the nation’s pits were closed.

The strike was solid in the Forest, including both union and non-union men, buttymen, and company men. FDMA members, who received strike pay, voted at a meeting in Speech House to provide relief to non-union men from their General Accident fund.[64] It was the biggest strike Britain had ever seen and for more than a month, the nation’s pits were closed.

However, the result was only a partial victory for the miners after government intervention established the principle of a locally negotiated minimum wage under the new Coal Mines (Minimum Wage) Act 1912. The government argued that the difficulty of issues such as the diversity of conditions and classes of work, especially for day men, could only be overcome by a decision that the individual minimum wage would be arranged by the district itself and be as near as possible to the present wages. In fact, nationally, the majority of miners rejected the settlement, arguing for a nationally agreed minimum wage, but the MFGB Executive overruled this at a special conference.[65] The local minimum wage was to be decided by district boards under an independent Chairman. In the Forest of Dean, the Chairman was the local aristocrat and Tory, Russell Kerr.

As a result, men working in abnormal places were now at least guaranteed a minimum wage. This included the buttymen, who were also required to pay their men a minimum wage. This was the very demand made by Rymer in the 1880s and had taken thirty years of campaigning to achieve it.

In the Forest of Dean, the rates were negotiated based on the base rate of 1888 plus the existing percentage. In 1912, this was 4s plus 30 per cent, giving a day rate for hewers and buttymen of 5s 2d. This was at least 2s below the larger coalfields where the price of coal and productivity, because of better conditions, was higher.

The agreement for most districts included a stipulation that no adult over 22 and under 65 should receive less than 5s per shift and no boy less than 2s. This was roughly the average pre-war working wage. However, in the Forest pits, Rowlinson agreed to an exemption from this stipulation. He gave in to pressure from the colliery owners and argued that it could lead to men and boys being thrown out of work as higher wages could threaten the viability of the Forest pits. As a result, the day men would receive less depending on age and experience on a scale down to 1s 3d for the boys. Consequently, the pay of some of the men was below the recently set national minimum rate. For example, the skilled timbermen were to receive a minimum of 4s a shift. This arrangement was primarily suited to the buttymen because it reduced the wages they had to pay their daymen.

However, the introduction of the Minimum Wage Act transformed the nature of the butty system in the Forest of Dean. The Act meant that the daymen were guaranteed a minimum wage in law and were no longer subject to the whims of the buttymen in terms of their earnings. Secondly, the buttymen themselves were guaranteed a minimum wage. If their earnings were not high enough to pay the day men the statutory amount, then the company was required by law to make up the difference and provide a minimum rate for the buttyman himself.

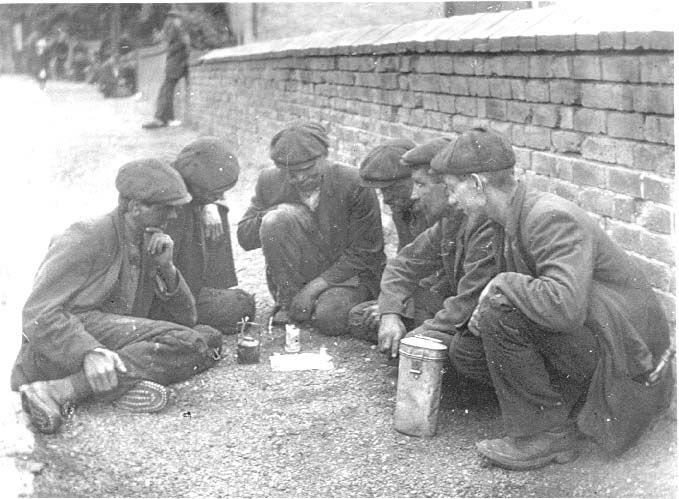

CHAPTER FOUR

TWENTIETH CENTURY

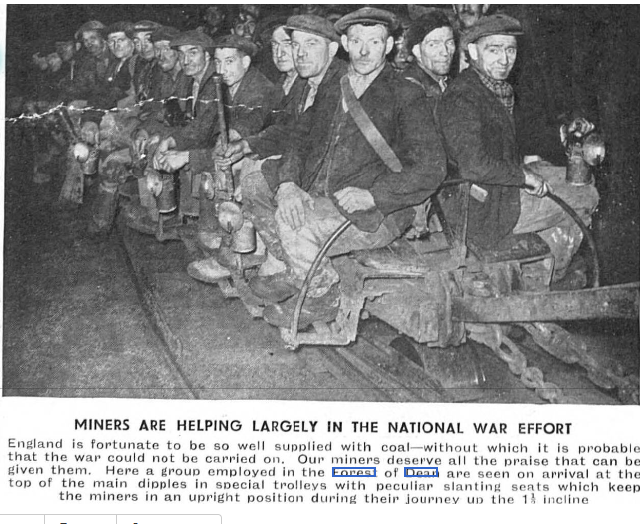

Also, by the twentieth century, there were no records of buttymen employing the large number of workers mentioned earlier. lan Marfell, who worked at Trafalgar Colliery in the early 1920s, probably sums up a typical arrangement:

Will Reed and Frank Arkell were the two buttymen and had several other men working for them, who were paid a daily wage. Any money earned over and above that was shared by the two buttymen. This system was used in all the house-coal collieries at the time.[66]

By the 1920s, most teams in the Forest of Dean consisted of a butty or a pair of butties with one or two day men and a boy, although some teams were larger and the system varied from pit to pit. In 1929, at Eastern United, the teams varied from about four men up to about nine men.[67]

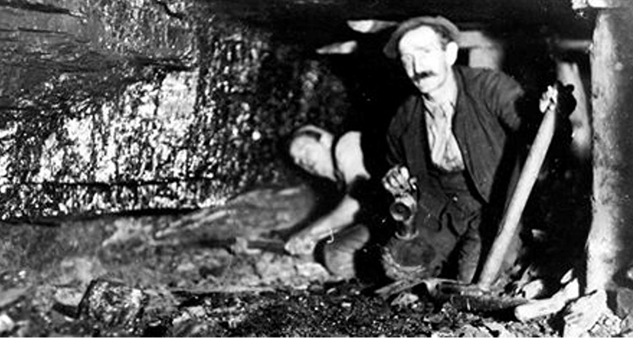

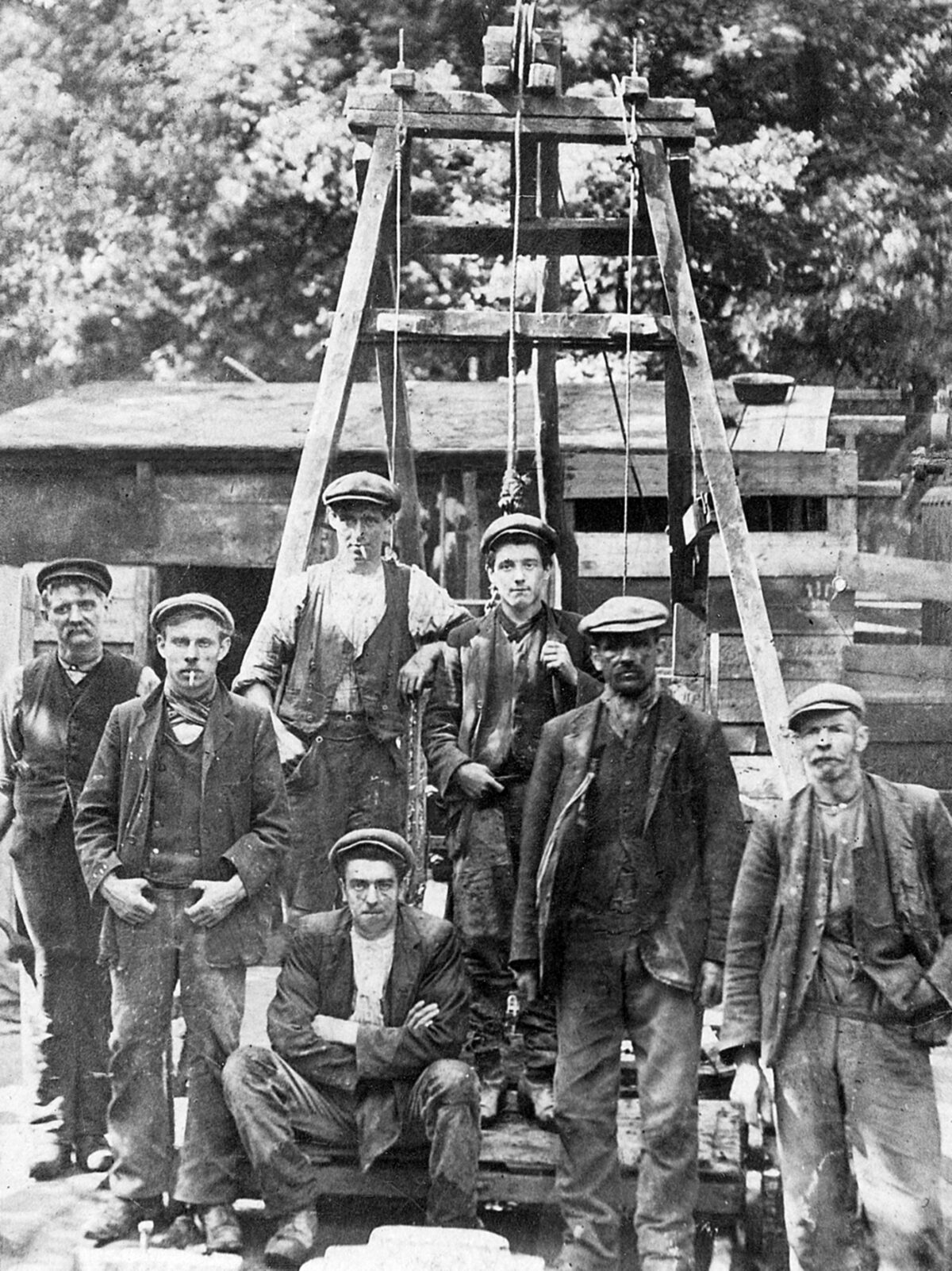

In the early 1920s, coal in the Forest of Dean was still extracted by hand and in most cases, the buttymen were directly involved with hewing coal themselves. The buttyman and his team performed the complete operation of coal extraction, which included the undercutting of the seams, digging out the coal and filling the drams. They could also be involved in timbering and driving new roadways to transport coal and access the coal faces, often using explosives, all paid on piece rates. The degree of job control enjoyed by the buttyman was still almost complete. The buttyman was autonomous in the organisation of his work tasks and responsible for all aspects of coal extraction with little external supervision. This was highly skilled work and based almost exclusively on knowledge gained through extensive experience in coal extraction in a range of geological conditions. Albert Meek explained:

Then you got rock road to drive and one thing and another; timbering – we were complete colliers we used to do the shot firing. They’ve got shot firing separate these days. We used to do all the timbering and we used to do everything that you could call a collier. You had to be complete colliers at that time.[68]

Since the buttyman was almost in complete control of the labour process and his remuneration was dependent on the amount of coal sent to the surface, he had the power and incentive to make sure his team was fully employed and worked hard throughout the shift, which sometimes could lead to bullying and exploitation.

Since the buttymen were paid on piece rates and acted as supervisors, there was still no need for micro-management of the teams working deep in the mine. In addition, the buttymen employed their day men, so the colliery owners had no employment obligations such as supervision and the hiring and firing of labourers. At the same time, the colliery owners received their profits while relegating responsibility for organising the hewing process and the disciplining of the workers to the buttymen.

However, there was now some oversight by underground officials directly employed by the colliery company. The deputies were charged with the supervision of safety, the ventilation of the workings, the inspection of timber work, etc. The deputies were responsible to the overman who was in charge of all the workings and was directly responsible to management. In addition, the daymen were listed on the company books so colliery owners could be held responsible in the case of accidents and the colliery owners were obliged to pay compensation in the cases of death or injury. This could mean there was no deterrent for the buttymen to take risks.

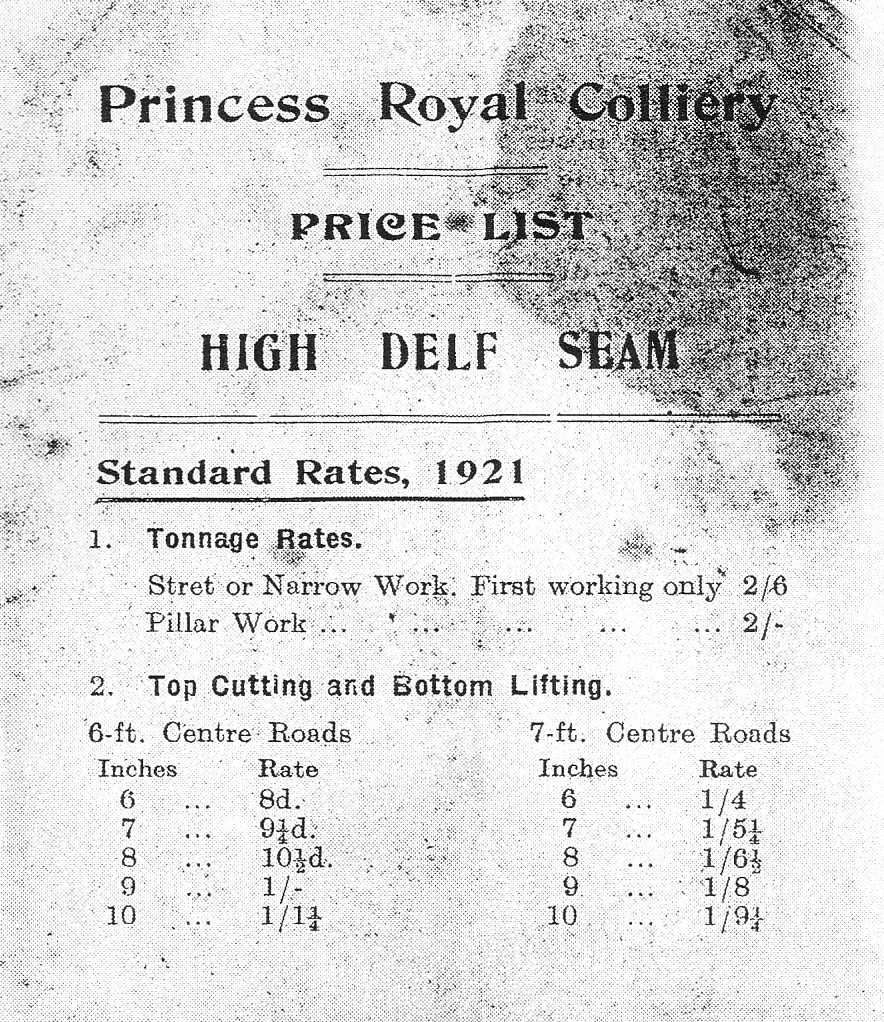

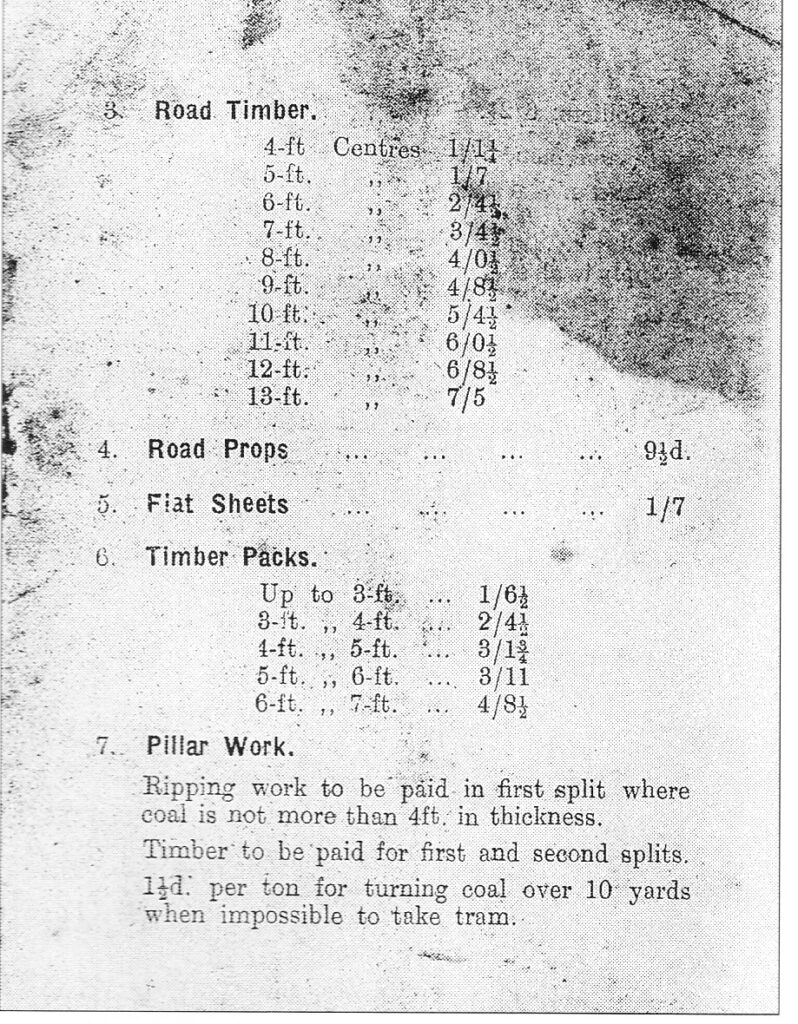

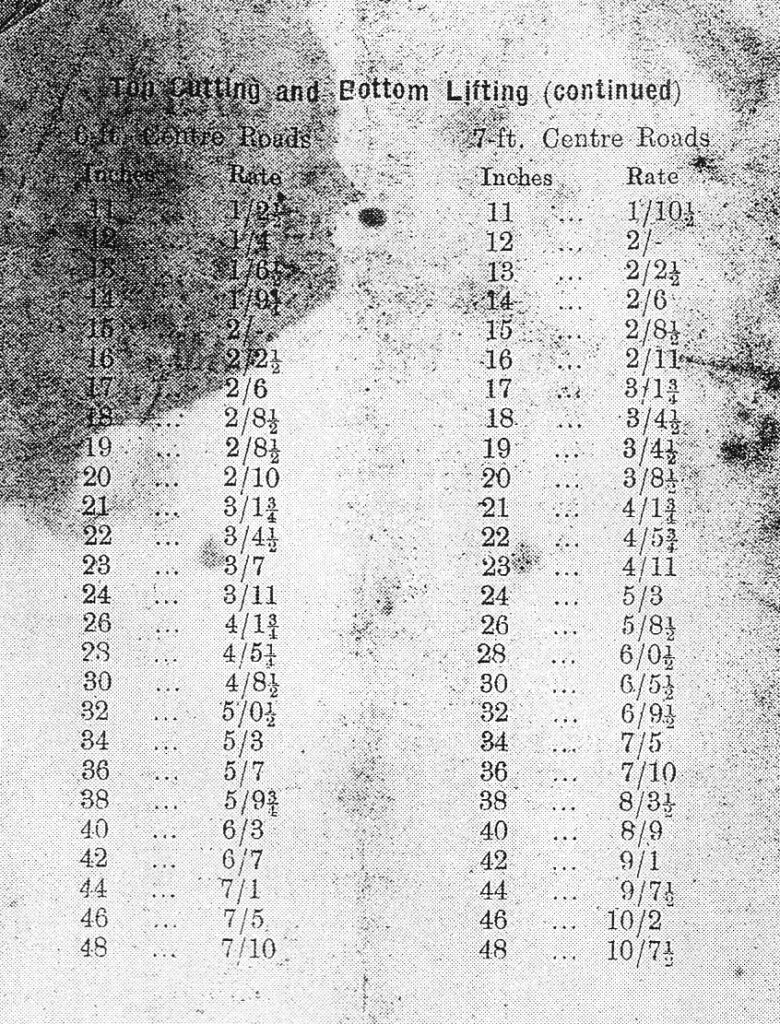

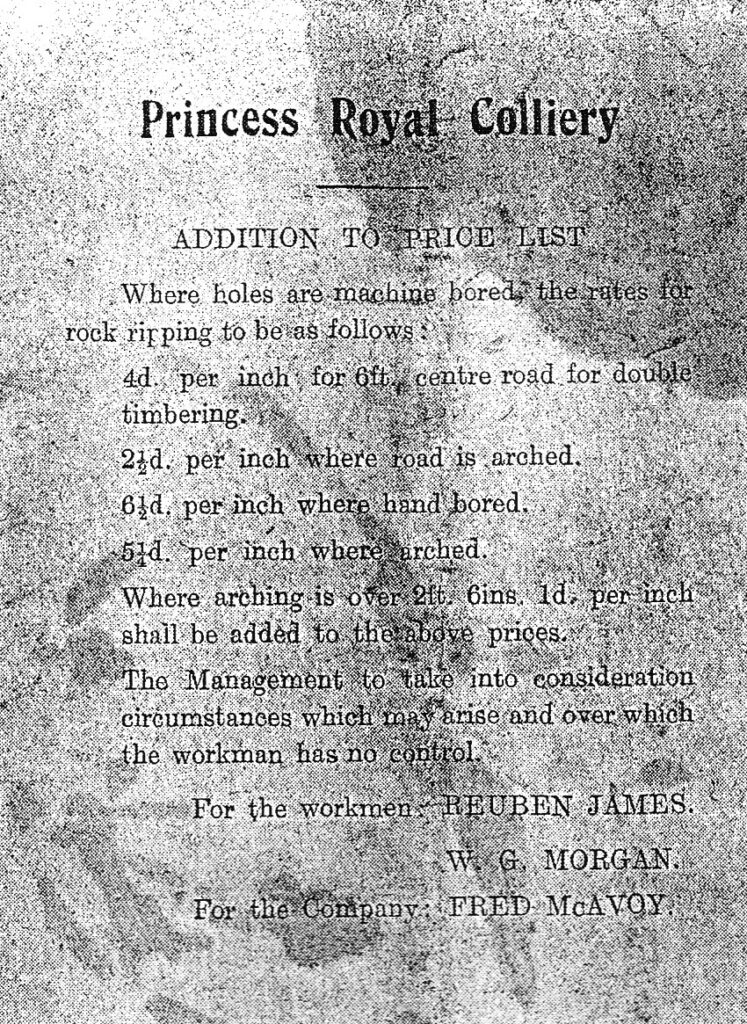

Price Lists

In most pits, an agreement between the FDMA and colliery owners included a detailed price list that listed the tonnage rates for coal produced and a piecework rate for a whole range of other jobs such as road ripping (paid by the yard), installing and repairing timberwork and associated work such as clearing dirt, which was not directly productive.[69]

The price lists were regularly reviewed by the colliery management, usually by negotiation with the FDMA and the buttymen. These negotiations took place all the time and often on the spot. If the issue was not resolved, the team could down tools, leading to a strike involving the whole pit. This was the case in 1909 when six buttymen came out in a dispute over the cutting of a pillar of coal at Flour Mill colliery. When the owners sacked the buttymen, the rest of the 700 men also came out on strike in support. As a result, the owners threatened to close the pit. However, the men returned to work after two weeks when concessions were made on both sides.[70]

At the time of the 1926 Lock Out, a Cinderford miner explained in a letter to the Gloucester Citizen how the butty system operated:

According to the agreement, every collier knows that there is what is known as a basic rate for cutting coal, timbering, etc. This varies according to the seam of coal worked, for instance: the ” Starkey ” vein of coal, which is from 12 inches to 14 inches thick, has the highest price per ton, namely 3s. 9d., plus a percentage, which in any case would not be more than 7s 6d at the rate paid before the stoppage.

The basic rate paid for making a road 10 feet wide by 7 feet high is 10s. per yard, plus of course 80 per cent according to the new terms in this seam. The roof to be taken down would be 5ft. 6in in thickness and 9ft. in width, and if any timber were required the price per pair would be 1s. 9d. plus, of course, percentage, and 2s. 6d. for partong caps, that is timber where two roads are separating.[71]

Trade Unionism

Most Forest buttymen identified with the principles of trade unionism and often were active members of the FDMA who supported them in their conflicts and negotiations with the colliery owners. The FDMA was involved in most negotiations to prevent buttymen from competing for contracts or undermining each other by offering low contract rates. In fact, even up to the 1920s, the FDMA was effectively a buttyman’s union and most disputes were driven purely by buttymen’s concerns, such as price list and tonnage rates, the condition of the seams, water in the pit, the extra allowances for dead work, conflict over dirt in the coal and so forth.[72] In the early 1920s, the majority of the FDMA Executive Committee were still buttymen or checkweighmen.

One example was Jesse Hodges (1880 – 1964), who was born in Nailbridge, near Cinderford. He started to work in an iron mine as a boy and then moved to Crump Meadow colliery where he worked his way up to be a buttyman, employing his son, Jesse Hodges (Jnr), as a labourer and hodder. Jesse Hodges (Snr) was then elected to the post of checkweighman and represented Crump Meadow on the FDMA Executive during the lockouts of 1921 and 1926.

Systems of Work

One of the factors affecting the earnings of the buttymen was the type of working system used and the number of men and boys in their team. The pillar and stall system was used on the lower, thicker steam coal seams, such as the Coleford High Delf vein. In this system, the stalls were about 3-5 yds wide and the seams were up to about 2 yds in depth. Pillars of coal were left behind to support the roof as the seam moved forward and then usually removed at a later stage. The thickness of the seam gave sufficient height for the drams to be brought practically right up to the face, where they could be loaded with coal and taken by the trammer to the main road.

In this system, the buttymen often worked in a partnership of two or three men (butties) to cover two or three shifts in the same stall with just one day man on each shift and usually a boy working as a trammer and labourer. Forest miner Len Biddington described the system:

There’d be three butty men, one for mornings, one for evenings and another for nights, for each stall and two men at a stall. The butty man would have a man he’d pay day wages, the butty men were paid on the coal and the yardage and all the overplus would be shared out between the dree butty men.[73]

The longwall system of working was used in the house coal collieries on the upper, thinner house coal seams. This system of extracting coal involved driving two advance tunnels or headings about 100 yards to 120 yards apart and extracting the coal from between the two headings. The width of the stalls or sections of the seam to be worked by each team could vary from about 15 to 40 yards. Rubbish was thrown into the gob, which was the empty waste area behind the face, which was allowed to gradually collapse in a controlled manner as the face advanced.[74] Alan Marfell described the technique at Trafalgar colliery in the 1920s:

Sometimes the seam was only eighteen inches high (or even less) to work under. You had to learn how to work under that height, how to lie out to use a pick, how to use a sledge for driving a wedge to bring the coal down after undercutting, and how to use a shovel to put your undercutting in the ‘gob’ behind you.[75]

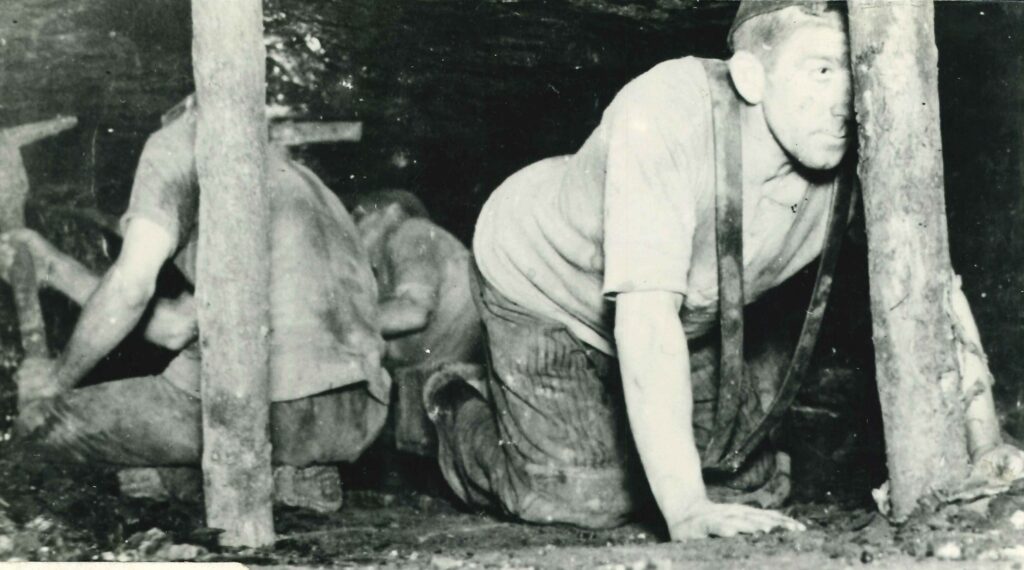

The thinness of the seams meant that teenage hodders were employed to drag the coal out from the face under a roof, which sometimes was only about 18 inches high, and then along a small trolley or hod road to a larger road that ran parallel to the face.

The system usually required more day men, including at least two hewers, hodders and possibly a trammer or filler on each shift, although in some instances two butties would work with one hodder. In 1922, J W F Rowe described the Forest of Dean longwall system in this way:

The stalls usually extend 15 to 20 yards each side of the ‘trolley’ road, or gateway leading back to the main road. In each stall, there are two, three, or four hewers, who do all the work at the face. When the coal is broken out, it is collected by a ‘hod boy’. The trolley road is often very low as it nears the face, and the hod boy may have to take his hod a considerable number of yards down the trolley road before emptying it into the trolley. When it is full the trolley is pushed by hand back to the main road, and then it is emptied into a tram or large truck, which is taken by horses to the shaft. The tram is loaded by a filler, and the hand-putting of the trolley may be done either by him or by the hod boy. The hod holds about two scuttles-full, the trolley about 8 to 10 hundredweights, and the tram anything from 20 to 30 hundredweights …. Two of the hewers or sometimes three, share equally, and employ other men at the face, together with the hod boy and, the filler, all on day rates.[76]

The buttymen and the hewers were regarded as the elite of the workforce, but they worked in the most difficult and dangerous conditions, and this was particularly so for those working the thin seams in the house coal pits. Life for the day wage hewer was hard, but an inspection of inquest reports into deaths in Forest mines reveals that most buttymen were also directly involved in the physical work on the coalface. According to Jesse Hodges (Jnr), who worked for his father, who was a buttyman, the work in the house coal collieries was particularly hard:

You had to lie on your side, you dragged on your side in a way or on your belly, to get the coal out. I’ve seen men, “Mollie” Morris he was a great big man, he used to work in thirteen inches, he used to squeeze his stomach right in. He worked on his side and it was wet, water coming down all the time in that seam, and you dragged yourself in and you dragged yourself out and men worked in that. They lay on their sides to work, hauling the coal out. There was hardly any room to use your pick … And that’s how that was done. That’s what I said, we were animals. We were classed as animals and treated as such. They were bad old bosses in those days. They were the boss and you had to beg for bread.[77]

Forest miner, Eric Warren, described the difference between the men working on the face in the house coal and steam coal pits:

You could always tell a house coal collier from a steam coal collier. The house coal collier was thicker in the shoulder. He had to lie on his back to work. He did everything from that position. There wasn’t a tougher man in Britain than the house coal collier, he worked hard, played hard and drank hard.[78]

Hodding

Hodding was used in the house coal pits to transport coal from the coal face to the drams in a hod, which was a large wooden box on skids.[79] Most of the hodders were teenage boys (14 plus) and in the 1920s they would start on about 20d a day, but their pay would improve with their skill and age. Those who volunteered may have preferred hodding to other jobs such as working on the screens, or ‘road zwippin’ where they would only get 10d a day. In addition, hodding provided an opportunity to learn the skills of a hewer and the status involved.

Hodders had to drag the hod along by hand and knees using a chain attached to a leather harness that ran between their legs and over their shoulders. Some of the seams were only about 12 to 18 inches high, so the work often resulted in injuries to their back, knees and private parts.[80] Fred Warren started work as a hodder at Foxes Bridge Colliery in 1913 and described his first day at work as follows:

Oh, I d’ aim I was 14 or more, just about 14, because we had to go up to the pit in the morning, stand by the cabins and see all the men go down and if there were two butties on there and they hadn’t got nurn a boy, they would come out and look around at you. You were like cattle in a market. They would look at you and if your backside did stick out a bit, they did say “he might be able to do a bit of hodding”.[81]

Similarly, Albert Meek who was born in 1898 and started work at Crump Meadow in 1911 said:

You’d cry all day and you would cry all night. You would get sore shoulders; you would get sore knees. And you would say to your parents “what would you do for my sore knees?” “Put them in the jerry!”[82]

Fathers and Sons

Attitudes towards the buttymen within the mining community still differed. Some viewed them as exploiters and others viewed them as highly skilled men who deserved to be paid more for their extra responsibilities and skill than the less experienced and often younger daymen. Molly Curtis, born in 1912, remembers that her father, who was a buttyman, earned more than the daymen but complained about his responsibilities:

They used to have “places” and then they had to share out the money and dad used to say “Oh, ‘I hate it on a Friday when I can’t give those men as much as I feel they earned ‘…….Dad was the keeper of the place, you know it was his “place”. He had a lot of responsibilities, you know, and sometimes he used to say if he couldn’t get enough coal out, then he used to have to go back grovelling to the manager and they didn’t like grovelling.[83]

It was quite usual for young boys to start their mining career working for their fathers, and often, hewing teams were made up of fathers, brothers and sons. It was likely that many young, skilled miners aspired to follow in the footsteps of their fathers to become their own working masters with their own stalls or section of seam to work. Harry Barton started work for his father just before World War One. After serving in the military, he returned to the pit and later became an active member of the FDMA and a member of the Communist Party:

Now when I was about 17 my grandfather, who was a ‘Butty-man’ with my father, he retired when he got old, he got the coal dust on his lungs. And father said to me one day he was going to take me in with him as a ‘butty’, so I was a butty. That was all right by me because we paid the men who were working for us and we shared the money out between us afterwards. I used to work it out what the men’s wages were who were working for us. And I used to work it out on paper the night before, on the Thursday night. Well, when we were at work the next day I would go to the main office after we came out of the pit and draw the money out from there. I’d put it down on paper what these men were due to be paid out of the money I had picked up. Whatever was left over I shared between my father and me, that was the butty system.[84]

At Lightmoor, a Forest house coal colliery, a buttyman could work the same area of the colliery for many years and the places or roads were often named after him. Harry Barton, whose father and grandfather were buttymen, remembers working for his father at Lightmoor:

This road was nearly a mile long from the main road which we called ‘Barton’s Road’. My grandfather and father worked that road. The next road below was 30 yards on down, then there was another road which was called ‘Morse’s Road’, that meant, you were from Ruspidge. On a little bit further was ‘Woolford’s Road’.[85]

Hierarchy of wealth

However, the butty system created inequality in earnings and status. Some miners, particularly the buttymen, owned more than one house and maybe managed or owned a pub or a shop and some land, while the daymen were more likely to be tenants or lodgers with no other extra means of support. In fact, there was a long tradition of buttymen owning or managing pubs in the Forest. Harry Barton was born in the Kings Head Hotel in Cinderford, which was managed for about six years by his father, who worked as a buttyman at Lightmoor colliery.[86]

As a result of the hierarchy of wealth and status among the miners themselves, there were significant differences in levels of poverty within the community. Winifred Foley, in her account of a 1920s childhood in the Forest of Dean, recalls:

The women from the better-off end of the village and a sprinkling of the husbands were regular chapel-goers. Not so the other end. All too often the poorer women ‘hadn’t a rag to their backs good enough for chapel!’[87]

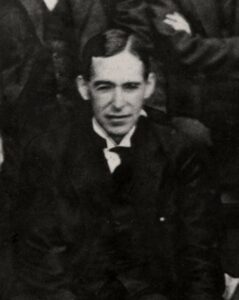

CHAPTER FIVE

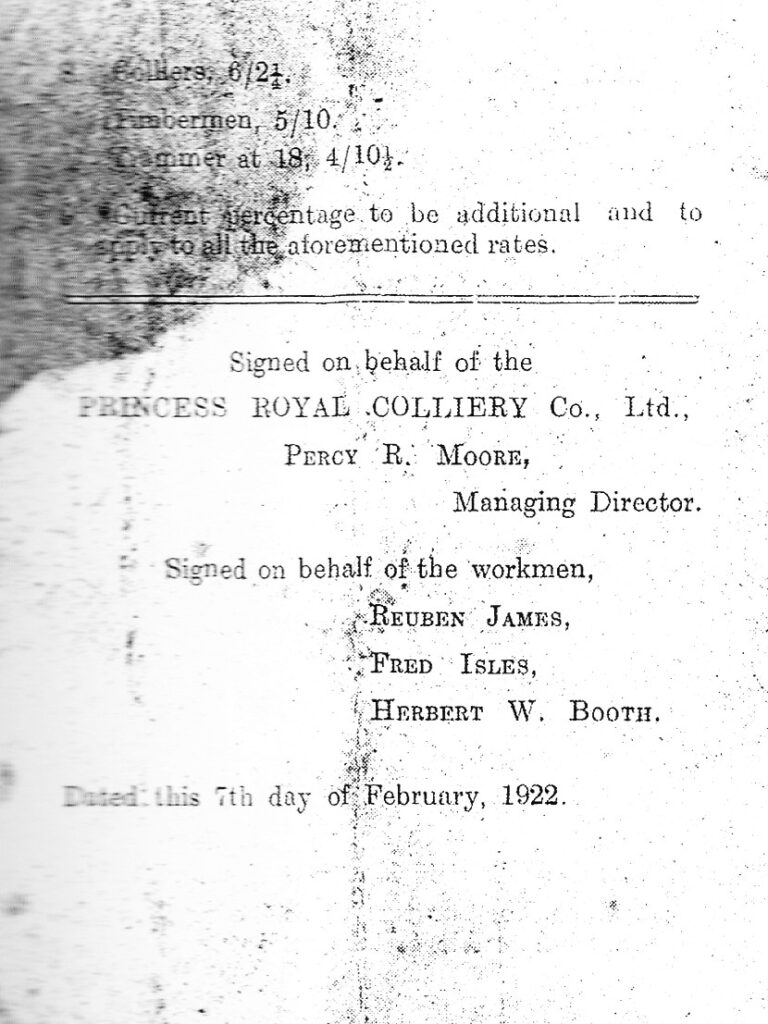

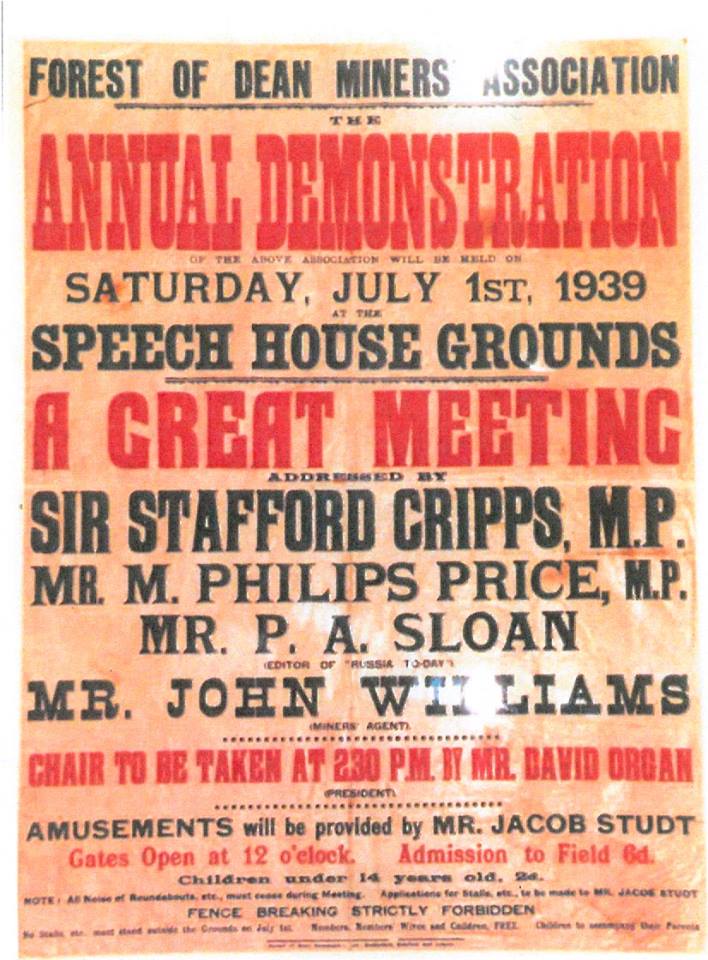

HERBERT BOOTH