Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History reserve the copyright of this article but give permission for parts to be reproduced or published provided Ian Wright and Forest of Dean Social History are credited in full.

Introduction

This story starts in the Forest of Dean with a riot and song and ends with an account of the struggle for the human rights of the visually impaired in Australia.

The folk song As Sylvie Was Walking, made famous by Pentangle in 1969, has been traced to Ann Howell who was born in October 1832 at Broadwell Lane End, Forest of Dean, where she learnt it from her uncle. The Pentangle version, which can be viewed on YouTube, is called Once I had a Sweetheart and leaves out the first three verses.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3QoWdrY7zQg

The original version below is from Ralph Vaughan Williams and Albert Lancaster Lloyd (Editors), The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, Penguin, London, 1990, and is listed as collected from Mrs Aston, Australia, 1911:

As Sylvie was walking down by the riverside,

As Sylvie was walking down by the riverside,

And looking so sadly, and looking so sadly

And looking so sadly upon its swift tide.

She thought on the lover that left her in pride,

She thought on the lover that left her in pride,

On the banks of the meadow, on the banks of the meadow

On the banks of the meadow she sat down and cried.

And as she sat weeping, a young man came by

And as she sat weeping, a young man came by,

“What ails you, my jewel, what ails you, my jewel,

What ails you, my jewel and makes you to cry ?”

“I once had a sweetheart and now I have none.

I once had a sweetheart and now I have none.

He’s a-gone and he’s leaved me, he’s a-gone and he’s leaved me

He’s a-gone and he’s leaved me in sorrow to mourn.”

“One night in sweet slumber, I dream that I see,

One night in sweet slumber, I dream that I see,

My own dearest true love, my own dearest true love,

My own dearest true love come smiling to me.”

“But when I awoke and I found it not so,

but when I awoke and I found it not so,

Mine eyes were like fountains, mine eyes were like fountains

Mine eyes were like fountains where the water doth flow.”

“I’ll spread sail of silver and I’ll steer towards the sun.

I’ll spread sail of silver and I’ll steer towards the sun,

And my false love will weep, and my false love will weep

And my false love will weep for me after I’m gone.”

Ann was the daughter of George Howell (1806-1871) and Eliza Jones (1809 -1872) who married in October 1830. George worked as a coal miner and later as a postman. Diary journals, held by a descendant of the Astons in Victoria, describe George as being a little wild in his youth when he was fond of drinking and poaching. There is another reference to George being involved in the riots of 1831 when, just like the leader of the uprising Warren James, he ended up hiding from the military in a disused mine while his family brought him food. However, unlike Warren, he was not betrayed and went back to work in the pits. Sometime later he was involved in a subsidence accident which killed his workmate and, as a result, he “got religion and changed his ways”. It was after this that he became a postman. The Diary journals also mention George’s wife Eliza. She used to go to the coal mine for coal, with her donkey “Venture or Venter” and bring home sacks of coal. The diary records that sometimes she would be late and would hasten home through the lanes looking fearfully round in case one of the numerous ghosts of the locality appeared.

In December 1854, Ann married Edward Aston, born in September 1830 in nearby Five Acres, down the road from Broadwell Lane End. In 1851 Edward was working as an apprentice cordwainer or shoemaker with Isaiah Stephens at Berry Hill. Consequently, in 1855, Ann and Edward decided to emigrate to Australia which was attracting immigrants from all over the world, partly as a result of the discovery of gold. In 1852 alone, 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia and the economy of the nation boomed. The total population trebled from 430,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871.

Ann and Edward sailed from England in 1855 on the ship the John Banks, a voyage lasting four months. They arrived in Kapunda, Adelaide and their first daughter, Eliza, was born in December 1856. An uncle of Edward invited them to join him in Carisbrook in the State of Victoria where he lived. In 1854 the population of Carisbrook was only about one hundred but it quickly grew. The discovery of gold in Victoria led to towns springing up throughout the State providing opportunities for miners, tradesmen and shopkeepers. In the next two years, the State’s population grew from 77,000 to 540,000 and the 1850s Victoria contributed more than one-third of the world’s gold output.

Ann and Edward travelled by steamer to Sandridge and then continued up country by bullock wagon to Carisbrook with baby Eliza and all their processions. This was a journey of 100 miles and the track was rough. Eliza was quite sickly and her health was made worst by the constant jolting. As a result, Ann and Edward took it in turns to walk next to the wagon carrying Eliza in their arms. When they arrived, they had to live in a tent, but sadly Eliza died in December 1857.

Life began to improve for Ann and Edward when they moved into a house in the town where their daughter Charlotte (1857-1928) was born. They soon had two more children, William (1859 -1923) and Sophia (1861-1942). The district population increased dramatically in 1863 when gold was discovered at Majorca, 8km south of Carisbrook, and 15,000 gold diggers rushed to the area. More children followed with George (1863-1867), Stephen (1865-1935) and another Elisabeth (1867-1900). Tragically George drowned in a creek at the age of four. Matilda (Tilly) was born in December 1873, the last of eight children. Misfortune struck again when it was discovered that Tilly had a defect in her eyes and was partially sighted.

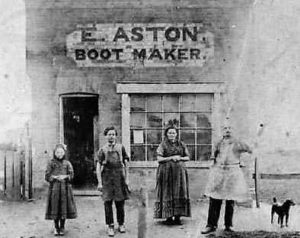

After the initial gold rush around Carisbrook, the mining moved to the North West, leaving a small population living off the land and a number of tradesmen and shopkeepers. At home, Ann continued to sing a range of ancient ballads and folk songs. Edward also passed on songs and tales from the Forest of Dean and the children learnt to sing before they could read. Edward joined the brass band which regularly played at public celebrations and funerals. In the evening the family often sat around the old harmonium singing revival hymns or folk songs with Edward and William accompanying them on the flute. The family joined the Wesleyan chapel, singing in the choir, and became popular members of the local community.

At school, Tilly used large-type books, from which she learned to read, write and memorize poetry and songs. However, just before her seventh birthday, she became totally blind. Misfortune struck again when Edward became ill and could only work part-time. Consequently, Ann had to start accepting money for work as a mid-wife, a service she had previously provided free of charge to her neighbours. In October 1881 Edward died. Ann had no choice but to extend her work as district nurse and mid-wife to support the three remaining children living at home.

Six months later Tilly met Thomas James, a miner who had lost his sight in an industrial accident and who had become an itinerant blind missionary. James introduced her to the Braille method of reading and she began to develop her interest in literature. After a visit to Carisbrook by the choir from the Victorian Asylum and School for the Blind in Melbourne, led by Reverend William Moss, Ann agreed to allow Tilly to attend the Asylum boarding school.

After about 20 years, deep mining returned to Carisbrook and brought with it miners from Cornwall and South Wales whose wild behaviours sometimes brought them into conflict with the settled inhabitants who were mainly Irish or English. Not only did the miners’ goats eat everything in sight and crime become a problem, but the deep mining undermined the foundations of Ann’s house, resulting in deep cracks in the brickwork and leaks. As a result, Ann and the remaining family moved to Moonee Ponds, near Melbourne.

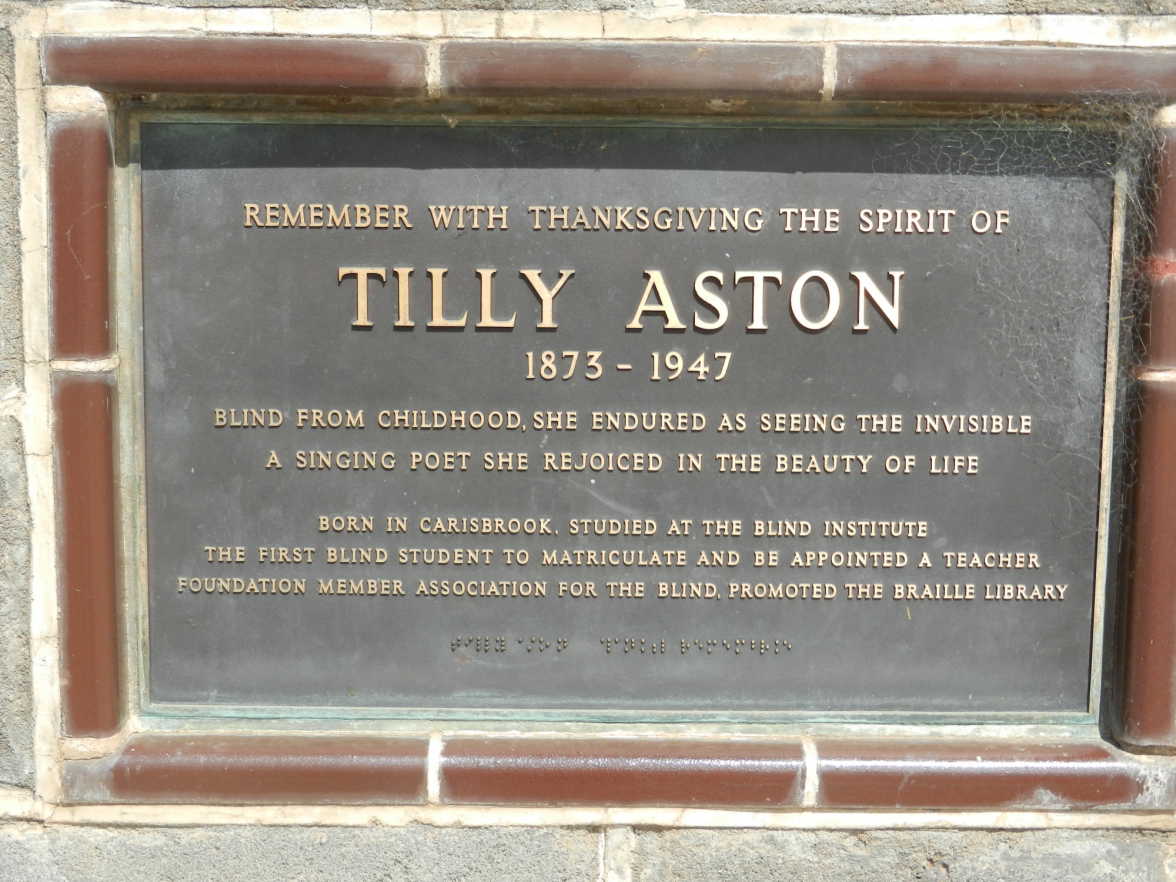

Tilly finished school at the age of 16 and went to live with her brother, Stephen, and their mother at Moonee Ponds. She enrolled in an arts degree at the University of Melbourne, the first blind Australian to do so. However, the lack of Braille books made it impossible for her to complete her degree, and she was bitterly disappointed when she had to discontinue in her second year. Such challenges became the impetus for her commitment to improving the lives of others with impaired vision. She passionately believed that the blind and partially sighted had the right to an education and the ability to run their own affairs.

To make education accessible to the vision impaired, she founded the Victorian Association of Braille Writers in 1894. The Association soon established training programs for sighted volunteers to learn and transcribe Braille and it went on to launch Victoria’s first Braille library. In December 1895, Tilly arranged a meeting resulting in the formation of the Association for the Advancement of the Blind, with the aim of improving conditions for the blind and partially sighted. The Association was run for and by the vision impaired which was a condition of membership. Tilly was its first secretary, serving for nine years in a post where she also assumed the duties of treasurer. When a decision was made to employ a paid secretary, she was elected President.

The Association worked to change Government policy and made contact with people who were vision impaired throughout Victoria, creating networks and carrying out regular visits. It provided financial relief for those in need and worked to increase employment opportunities. The Association forced the government to concede free postage for Braille material, transport concessions for the vision impaired and eventually won voting rights for blind people in 1902. In addition, Tilly successfully helped to lobby for the repeal of the bounty system which meant blind people had to pay hefty levies before they could travel interstate. She also gained government approval for a pension for all blind people. Many of these gains inspired the struggle for the human rights of vision impaired people internationally.

At this time Tilly started writing and in 1901 she published her first book, Maiden Verses. In 1904 she won the Prahran City Council’s competition for an original story. The Woolinappers or, Some Tales from the By-Ways of Methodism was published in 1905 and from September 1908 ‘The Straight Goer’ was serialized in the Spectator.

Ann died in 1913 and Stephen married and moved out of their shared accommodation. Tilly was unable to live alone and so moved to her own house in Windsor where she lived with the support of a housekeeper and companion. In the same year, she completed her teacher training and became head of the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind, the first visually impaired person to do so. Her appointment was criticised by staff and officials who did not approve of a visually impaired teacher. In addition, during her tenure, she was required to sever her connections with the societies she had helped to found. In spite of this, she proved to be a competent teacher and administrator, although her years at the school were not happy. She retired in 1925 and then devoted her life to campaigning and writing. She was also re-elected president of the Association for the Advancement of the Blind, a position she held until her death.

Her later books, which she drafted in Braille and then typed, included Singable Songs (1924) and Songs of Light (1935). ‘Gold from Old Diggings’ was serialized in the Bendigo Advertiser from August 1937 and Old Timers was published in 1938. She believed The Inner Garden (1940) contained her best work. Her sense of humour and courage are shown in her Memoirs of Tilly Aston (1946), written while a member of the Bread and Cheese Club, an Australian arts and literary society. All her books were published in Melbourne. For twelve years she edited and largely wrote A Book of Opals, a magazine issued in Braille for use in Chinese missionary schools. She was also a keen exponent of Esperanto and corresponded with fellow linguists all over the world. Tilly died in Windsor, Melbourne in 1947. A year later the Midlands Historical Society and Carisbrook school children erected a cairn to her memory.

This article first appeared in the Forest of Dean Local History Society Newsletter in 2017. Thanks to Chris O’Sullivan in Australia and Keith Walker from the Forest of Dean Local History Society for providing information and corrections to earlier drafts. Chris is related to Ann Aston through Ann’s sister Susan. Susan married Thomas Edwards in 1870 after his first wife died leaving him with three daughters. They then all emigrated to New South Wales in 1876 with their blended family. Chris kindly forwarded me a copy of Tilly’s memoirs and information from the family diary journals.

Some online sources

https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/a-diverse-state/the-girl-from-carisbrook/tilly-aston/

https://www.visionaustralia.org/community/news/2019-08-23/tilly-aston-poet-and-activist

https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/a-diverse-state/the-girl-from-carisbrook/tilly-aston/

http://www.womenaustralia.info/leaders/biogs/WLE0416b.htm

https://www.aussietowns.com.au/town/carisbrook-vic

http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~watkinsbrown/genealogy/memoirs_of_tilly_aston_australia.htm

http://www.simplyaustralia.net/?s=tilly+aston

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/aston-matilda-ann-tilly-5078

One reply on “As Sylvie Was Walking”

I enjoyed this article.