This is an account of my trips to South Yorkshire Coalfield in the Autumn of 1984 during the 1984/85 Miners’ Strike. It includes a description of my visit to Shireoaks Colliery in Worksop where I was a guest of friends, George and Christina Bell. I describe my experience of being attacked and beaten by the police while on the picket line at Maltby Colliery when I visited the pit with George in September 1984. Also included are accounts from the other members of the mining community and details of some of the events that took place at Maltby and Shireoaks during the strike.

At the time, I was living in London in a short-life Housing Association house in Shepherds Bush which I shared with two others. I was a member of Hammersmith and Fulham Miners Support Group, which was twinned with Sutton Manor Colliery in Lancashire. During the strike, miners from Sutton Manor, Shireoaks and Manton collieries (Worksop) stayed with us while they were in London for meetings or fundraising.

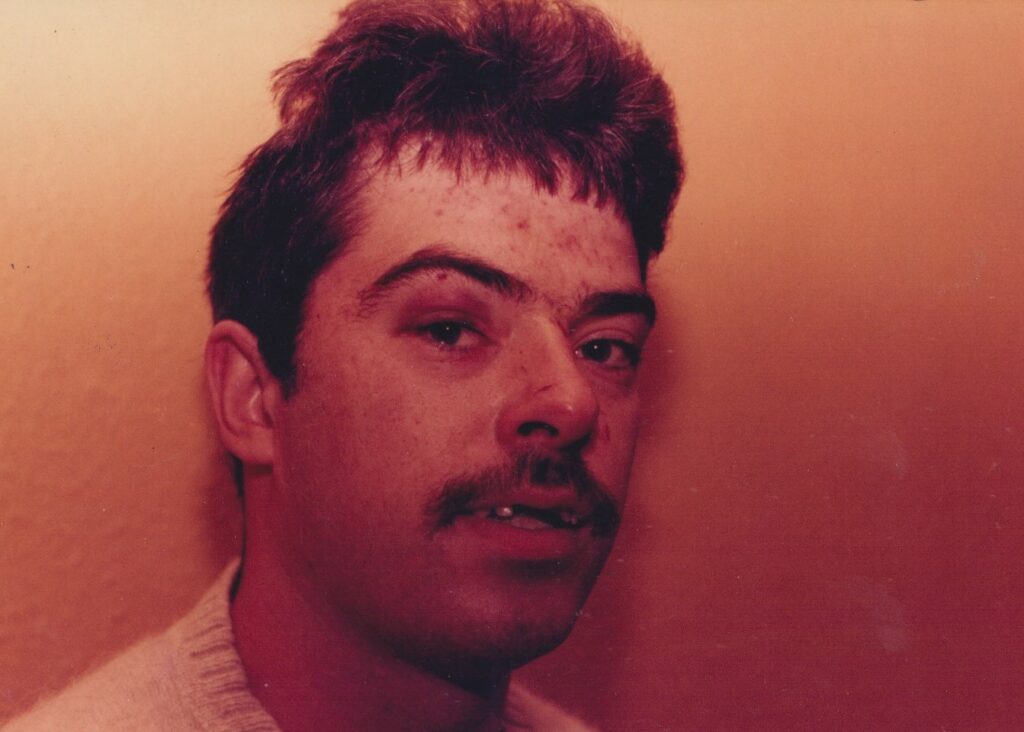

Ian Wright

We stood up to the establishment. Alright, we might not have won it, but we stood up for what we’ve believed in, we stood up for what we thought was right, and it’s worth remembering that people can still do this.[1] Christina Bell

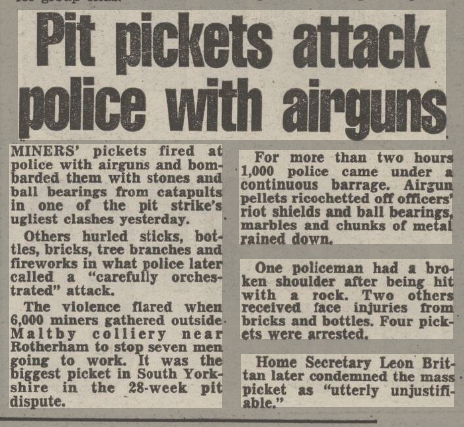

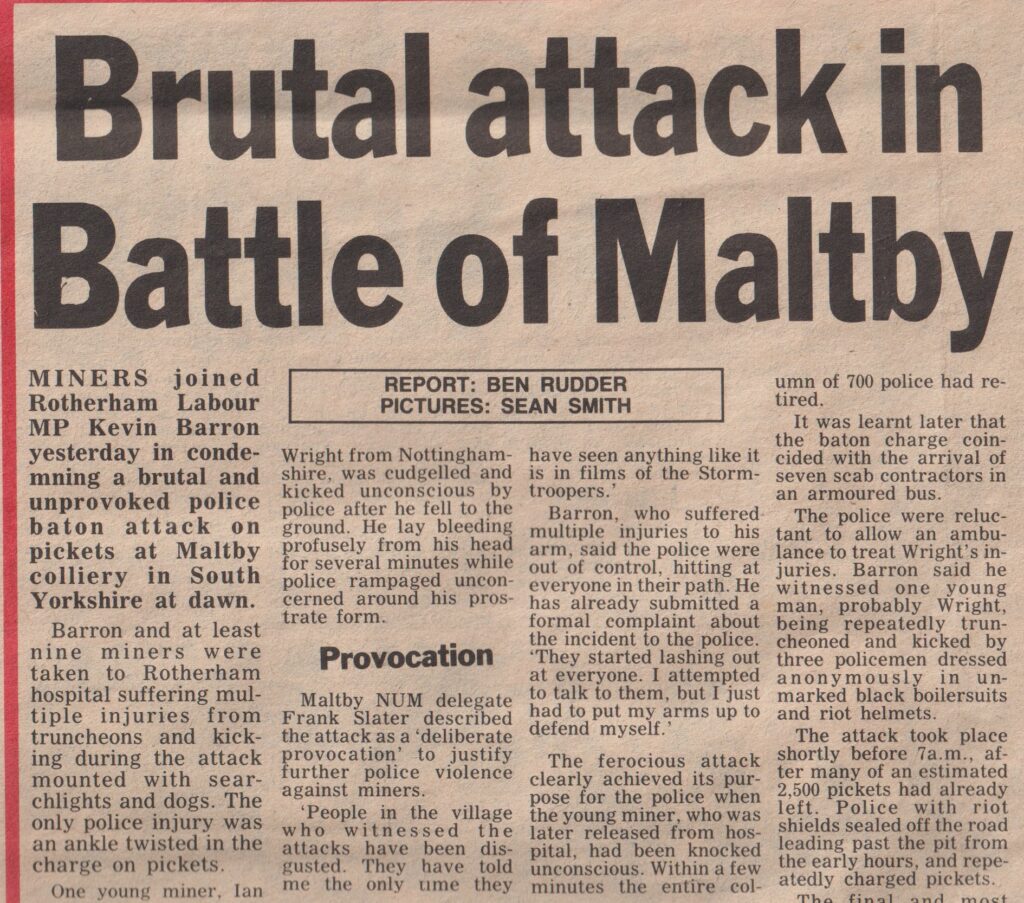

Towards the end of September 1984, the the right wing media claimed that there were running battles between “heavily outnumbered police” and “5000 violent pickets” at Maltby Colliery, South Yorkshire. They reported that the trouble started when police reinforcements were brought in from other areas to clear the way for some subcontractors to enter the pit to carry out development work.

News articles and TV commentators claimed that on Friday 21 September, there was a sustained attack lasting for about four hours by pickets using bricks, bottles and catapults firing rolled-up pieces of lead, ball bearings and marbles. The police claimed that dog handlers and their dogs in nearby woods were attacked with air guns and road signs. They added that walls near the pit entrance were torn down and used as missiles and to build barricades.

This is how the BBC and the Daily Mirror reported the Maltby picket of Friday 21 September.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUapdI7_KCg

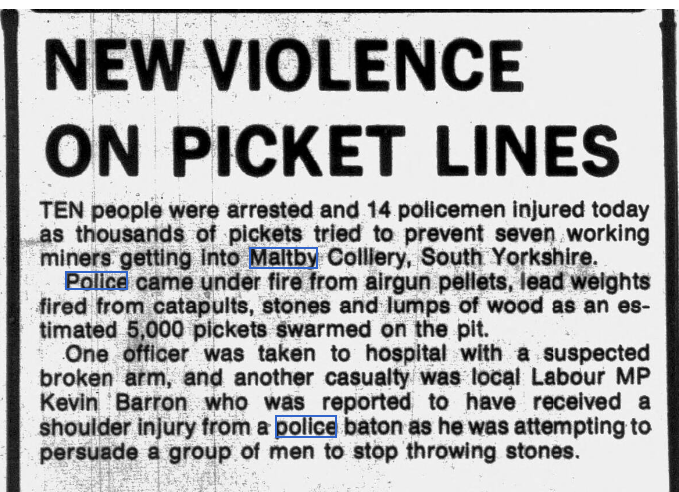

According to the newspapers, on the following Monday morning, violence erupted again outside Maltby Colliery, with pickets again using air guns and catapults against the police. The papers claimed this resulted in about ten arrests and about 14 policemen injured (although the numbers reported varied considerably). The Daily Express claimed that :

pickets opened fire with deadly new weapons…500 brave policemen faced 5,000 raging pickets.[2]

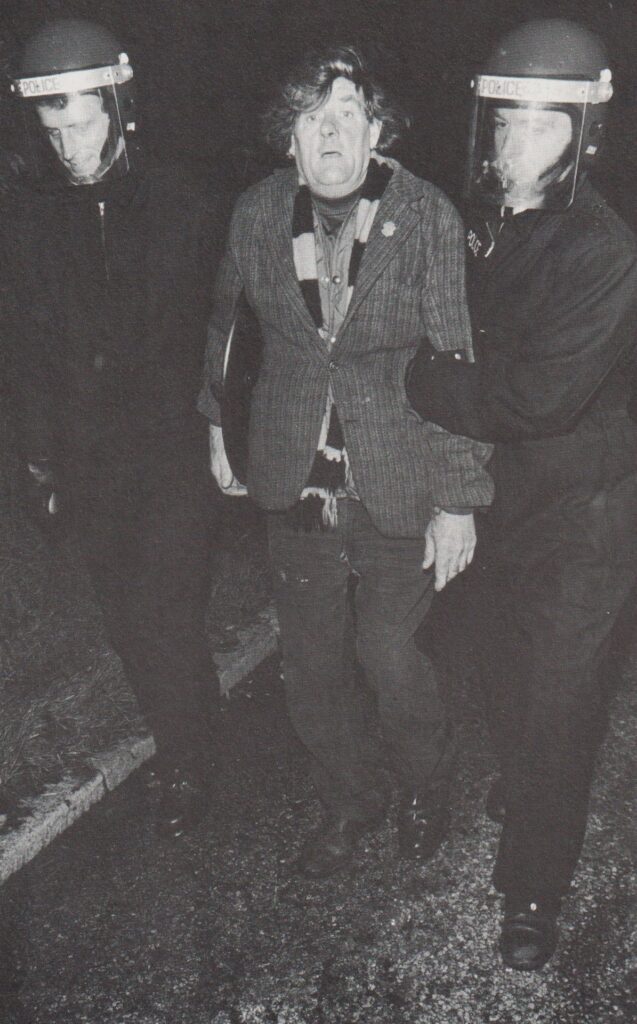

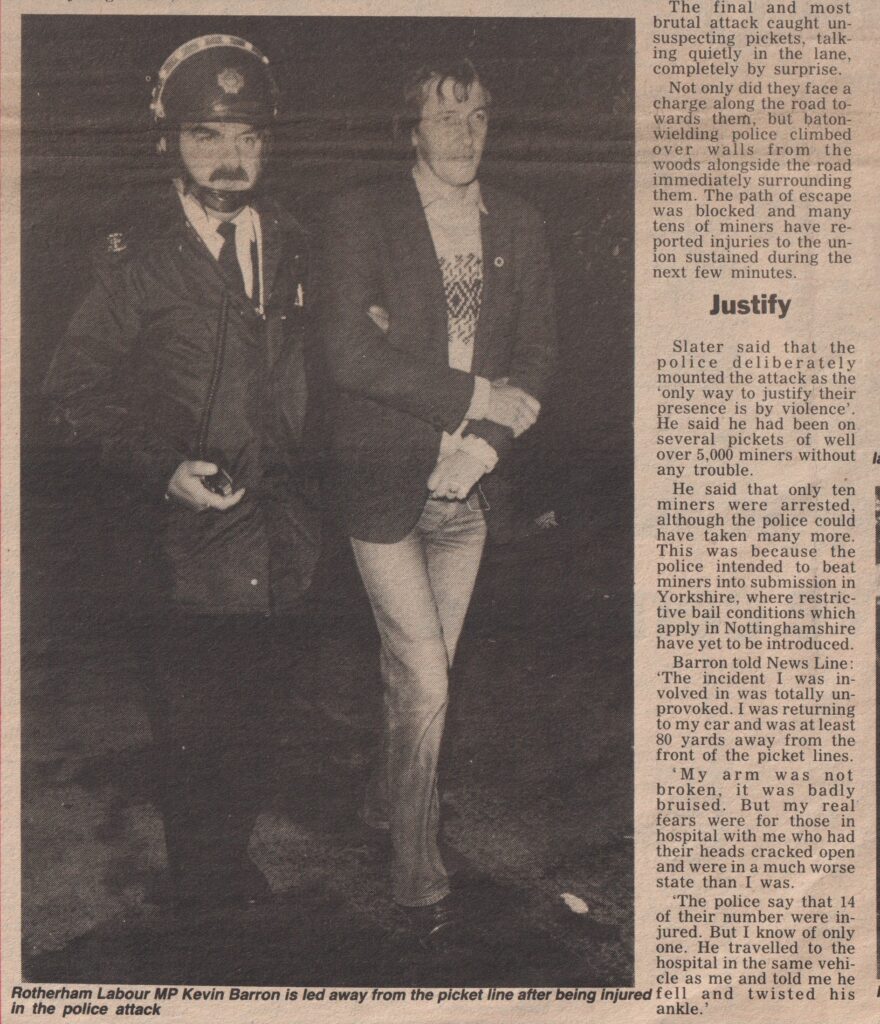

The reports added that the local Labour MP, Kevin Barron, suffered bruising to his arms after being attacked by the police while walking back to his car. Barron said:

The police were bludgeoning people to the ground. When I went back later there was still a pool of blood on the pavement. I have never seen anything so brutal in my life.[3]

In response, the Tory MP Eldon Griffiths, who is the Police Federation’s parliamentary adviser, called for the use of plastic bullets. The next day, the South Yorkshire Police Committee met with the Home Secretary, Leon Britain, who offered to review the government’s contribution to South Yorkshire’s policing costs. Except for the case of Kevin Barron, there was no mention of injuries to the pickets in the media. Here is a typical report on the events of Monday at Maltby.

Most of the reporting in the media amounted to a gross distortion of the truth and even outright lies. However, it was clear that in some cases the miners were fighting back, but in these cases, the reports failed to mention that the miners were responding to endless provocations. Emotions were running high and the tension between the police and the miners had deepened. The police increasingly behaved like a military occupying force taking over collieries and pit villages and communities felt they were under a state of siege. It was becoming clear that there was a danger the strike could be lost, collieries could be closed and jobs and communities destroyed. It was understandable that the miners were determined to fight back and defend themselves from an occupying hostile outside force, which appeared to represent their enemies in Thatcher’s Tory Party and the NCB. There was violence on both sides. However, the media reports consistently underplayed the offensive violence from the police and exaggerated the defensive violence from the pickets.

The Build-up to the Conflict

On 1 March, the National Coal Board (NCB) announced Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire would close in five weeks, having recently told its miners that the pit would stay open for another five years. The proposed closure of Cortonwood became the final straw in a series of closures which triggered the long-running UK miners’ strike of 1984–1985. On 5 March 1984, Cortonwood miners walked out on strike following a ballot and called on the Yorkshire Area NUM Council to call a strike of all its members. The Council agreed to do this and by the end of the week, the whole Yorkshire coalfield was on strike.

Neither Maltby Colliery nor Shireoaks Colliery in Worksop were threatened with closure. However, by 12 March, 1,350 miners at Maltby and 920 miners at Shireoaks had joined the strike out in solidarity. Most other mining communities followed suit and soon, with the backing of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) national Executive, a large majority of miners across the UK were on strike. However, some miners in the Midlands and Nottinghamshire remained at work. In response, pickets from Maltby and Shireoaks joined thousands of other Yorkshire miners descending on Nottinghamshire to persuade them to join the strike.

Tension between the Maltby community and the police erupted almost immediately when 30-year-old Frank Slater, a member of the Maltby (NUM) Lodge, who lived in nearby Worksop, was arrested on his way to the Nottinghamshire picket lines on Wednesday 21 March. The arrest occurred after his car ran out of petrol at a roundabout and the police asked him to identify himself. However, feeling threatened, he would not wind his window down, so the police smashed his windscreen.[4]

Slater was then dragged out of the car and charged with obstructing the highway and failing to stop when requested to do so. Also arrested and charged with obstructing the police was Stephen Kent (22). John Wallace (27). Kevin Wright (23). Darren Steele (19) and Ronald Marson, all from Maltby. Antony Wilson (33) from Maltby was charged with obstructing the highway and obstructing the police.[5]

June Disturbances in Maltby

The tension between the police and miners in Maltby continued but attitudes to picketing and how to respond to police violence varied. Disturbances broke out in the town over the weekend of 10-12 June, leading to confrontations between the police and youths. The next weekend, on Friday 17 June, two hundred young people gathered outside Maltby police station and attacked it with bricks and bottles for more than an hour and 16 arrests were made, of which eleven were miners.

The next day, many miners from Maltby headed off to Orgreave and joined one of the most violent events in British industrial history, where many miners became victims of brutal attacks by the police. On their return to Maltby on Saturday night, more trouble occurred and a riot broke out. The papers reported 29 arrests and 16 shop windows broken. Mr Ron Buck, 52-year-old magistrate and the Maltby NUM lodge secretary, condemned the smashing up of property:

I am making a plea to all mineworkers to cool it. There have been problems with policing here and on picket lines but it is my opinion we would be better off showing patience and going through the proper channels rather than people on street corners having a go themselves.[6]

However, others saw it differently. Jimmy Gavin, a member of the NUM Strike Committee at Maltby, said:

They can’t get us on the picket line so they are coming into the village to get us. We know it’s a planned military-style operation. [7]

Later in June, Keith Boyes, a member of NUM Maltby Lodge Committee, was interviewed by the Guardian and said:

I won’t be going back until I can see security for this industry. We never entered this dispute thinking it would last three weeks. We knew it could be six months because we have to erode 10 years of overproduction before we have any effect. Our branch members knew it would be a long strike. People kept on saying that the modern miner would never strike. But the way I look at my TV and video is that if they got burnt I would not lose a moment’s sleep. I regard materialistic things as a hobby. It’s when your backs are against the wall and how you react to those matters. And the Yorkshire miners have reacted in the same way we did in 1973, 1969, and 1926. Yorkshire miners’ families have learnt to adapt during the strike.[8]

In August 1984 tension between the police and young people in Maltby increased further because the police had begun to behave like an occupying military force. The Guardian reported that Buck warned there could be more trouble and that the young miners are “are not choir boys”.[9] He added that they were determined to stay solid and “aim to maintain the community, not just the pit”. Others from the Maltby community told the Guardian:

If you are born into a mining community it is all around you – this great thing holds you together and makes you stand up and fight.

It’s not so bad when you are sitting down next to someone in the same boat. (More than 300 midday meals are served in church, with dawn pickets eating first, then the men and their children.

There is nothing financial in it for us. it is all for our kids to have lobs. (Elizabeth Buck)

If I told my husband to go back, he’d throw me through the window. (Maltby Miner’s wife). [10]

September Disturbances in Maltby

The immediate trigger of the disturbances in September in Maltby was the action of the NCB. At this time, no miners had returned to work at Maltby but the NCB had arranged with Cementone Ltd, an outside construction contractor, to enter Maltby Colliery to carry out development work on the sinking of a new shaft. After meeting Maltby NUM, most of the fifty-odd Cementone workers had agreed to join NUM for the duration of the colliery contract and to refuse to cross the picket line or go to work until the strike was over.

However, the NCB found seven Cementone workers willing to cross the picket line and arranged with the police to provide protection and accompany them to work on Thursday, 20 September. This was a clear provocation because the seven workers would not be able to do much work but if the police could get them into the colliery, it would provide a symbolic victory to the NCB. In response, Maltby NUM arranged to picket their colliery and asked for help from other districts. However, on Thursday morning, the police outnumbered the pickets and managed to get the scabs into the pit. The Maltby NUM officials appealed for more support.

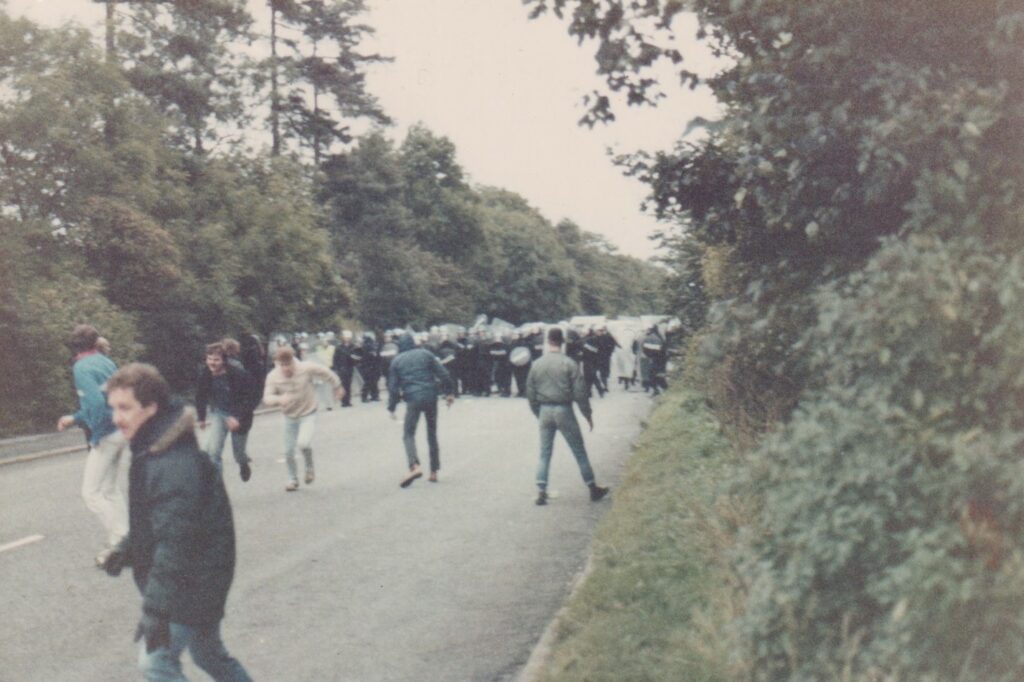

On Friday 21 September, about 2000 pickets were confronted by police horses and dogs from the South and West Yorkshire constabularies. Maltby NUM officials stated they witnessed 180 minivans full of police going into the Maltby pit yard with more following in coaches. Another attempt was made by the pickets to prevent the subcontractors from getting into the pit, but the police pushed them back up the road and were able to get a van containing the strike-breakers into the colliery yard by driving at speed through the pickets. Tension in the village increased over the weekend and led to a confrontation between Maltby miners and the police at a local Chinese takeaway.

On Monday, the confrontation between the police and pickets continued, but after the police had pushed the pickets back and allowed the van full of scabs to enter the pit, they brutally attacked the picket line from behind, resulting in serious injuries to several miners and their supporters.

The Daily Mirror’s and BBC’s coverage of these events listed at the start of this article was repeated in the mainstream media which continued to be hostile to the miners throughout the strike. The media stories were almost certainly sensationalist and exaggerated and did not tell the whole story. Statements from the miners who were there, pictures taken by John Sturrock and Newsline photographers and reports in trade union and socialist newspapers tell a different story. However, despite efforts, not a single report or image of police violence was reproduced on television or in the national press. In contrast, here are some alternative accounts of events of Monday 24 September.

Shireoaks

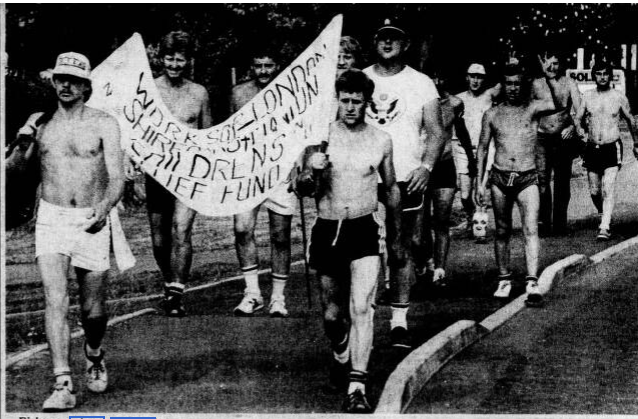

On Sunday 23 September 1984, Ian Wright and Ray Collingham from Hammersmith and Fulham Miners’ Support Group arrived in Worksop to stay with George and Christina Bell to learn about the strike at a grassroots level. Ian had made friends with George while working on a work brigade in Cuba in 1983 and George had stayed in London with Ian while organising a hunger March from Worksop to London in July. One local newspaper reported on the March as it went through Hinckley:

Eighteen miners marched through Hinckley on Thursday as part of a sponsored walk to London in a bid to raise money for striking miners’ children The men are walking from Worksop to London on a route that will cover 202 miles. They live and work in Worksop and Shireoaks where the schools have now shut for the holidays and the children can no longer eat free school meals So the men say they are hoping to raise money to buy food for their children “We can manage without” said one of the men “But our children can’t”.[11]

There were two pits in Worksop: Manton colliery and Shireoaks Colliery, where George was chair of the NUM lodge. At this time, all the miners at both pits were solidly behind the strike. On the evening of Sunday 23 September, George received a phone call that there was to be a picket outside Maltby Colliery at 5 am the next day.

On Monday 24 September, Ian and Ray rose early and drove north with George and other miners from Worksop about nine miles to join the picket line outside Maltby Colliery. However, before the morning was over, several pickets had been taken in an ambulance to Rotherham District Hospital because of the serious injuries they had suffered from truncheon blows, dog bites and beatings by the police. Here are the legal statements about the Monday picket issued by Ian Wright and Ray Collingham several weeks later followed by statements by other pickets and journalists.

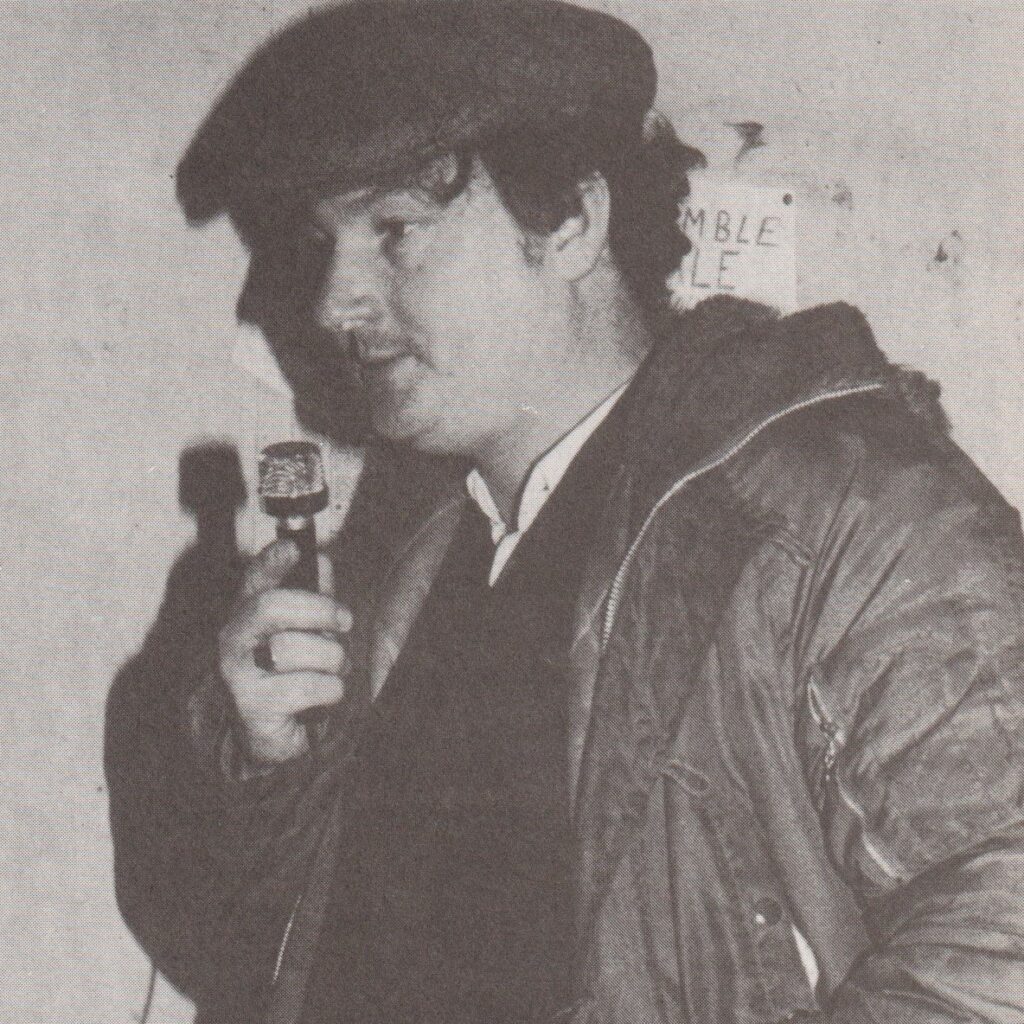

Statement from ian wright

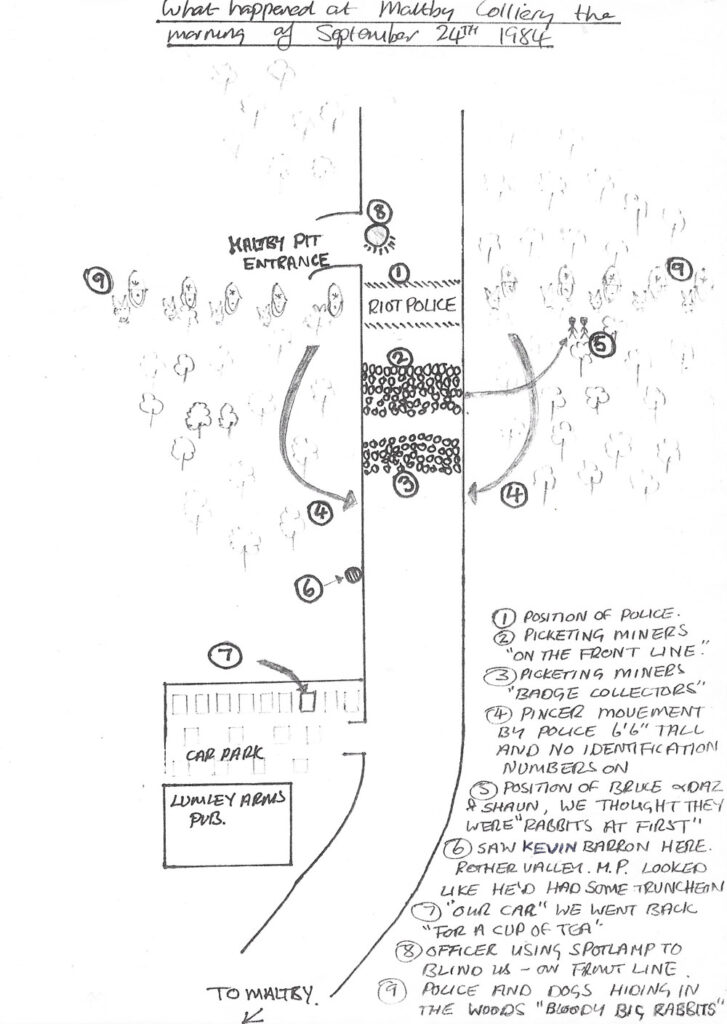

I attended the picket of Maltby Colliery on Monday 24 September as an observer from Hammersmith Miners Support Committee. I was with Ray Collingham, also from London, and George Bell, chairman of Shireoaks NUM. Ray and myself were staying with George and his family in Worksop. I know George well. He had stayed with me earlier in the summer while organising a hunger march from Worksop to London. He had invited Ray and myself up to Worksop to observe all aspects of the miners’ strike.

We arrived on Sunday 23 September. Monday was the first day we had gone out to observe a picket. George told us not to get involved with any picketing ourselves and to keep to the back. We arrived at Maltby at approximately 5.00 am. When we arrived, there were groups of men standing around chatting in the village and further down the road towards the pit. There were less than 1000 pickets. Further down the road, there were lines of police across the road with riot shields. They were shining search lamps up the road. There was no attempt by the pickets to break through the police lines. There was a small group of young men opposite the police lines, occasionally throwing stones at the police lines. However, most of the men were standing around in groups along the road towards the village, chatting.

The police had successfully blocked the road towards the pit and, now and again ran forward pushing the young men back up the road. I was standing further up the road towards Maltby with George and Ray, talking to people. As the road to the pit was blocked by the police, people were gradually leaving throughout the morning.

At about 6.30 am, the police managed to force the pickets back and drove a van at speed containing the seven scabs into the pit. Consequently, people started to leave and only about 200 people remained.

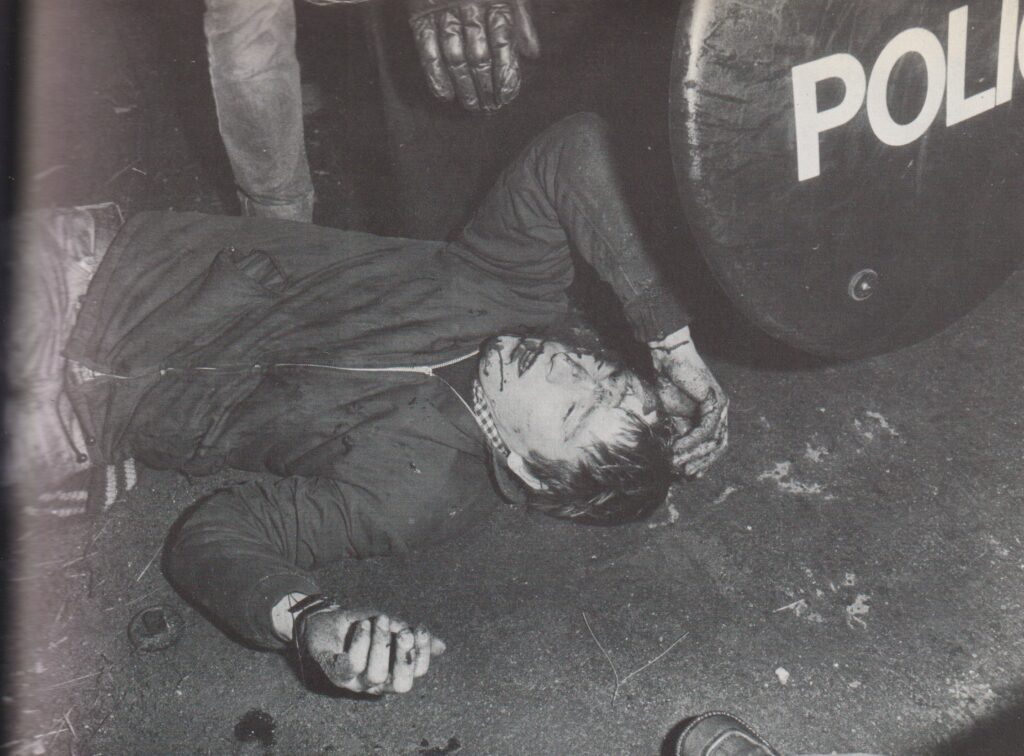

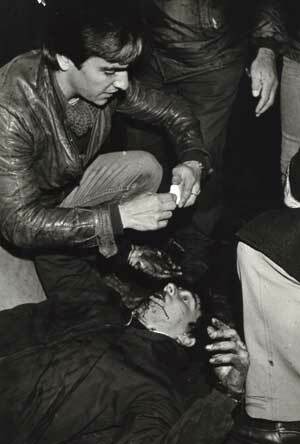

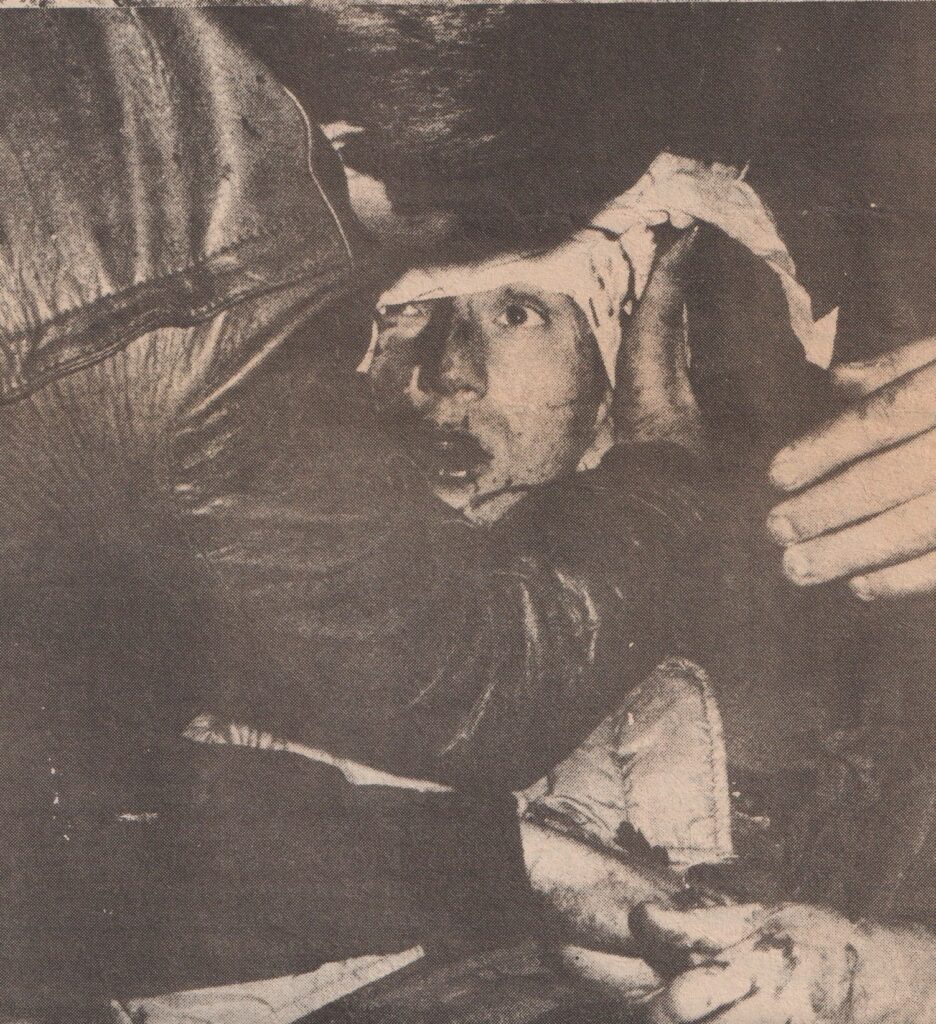

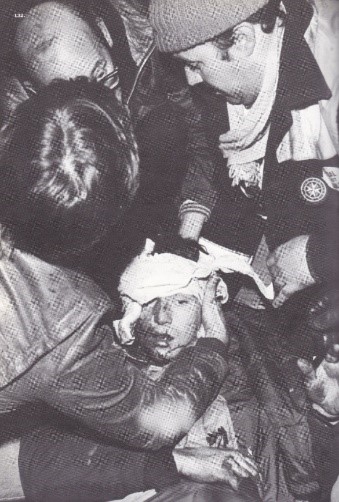

Not long after this, a group of police dressed in boiler suits with no numbers ran out of the woods opposite me, about 100 yards from the police lines, shouting obscenities. They had raised truncheons and full riot equipment. I tried to run, but a policeman hit me hard on the head with a truncheon. I collapsed to the ground. I tried to get up but was hit on the head again by a truncheon blow. I collapsed to the ground. I was then kicked while I was on the ground. All I could think was that I would die. I then crawled away into the bushes by the road and lay there. I felt the blood on my head and face. I felt someone pulling me from the bushes. Then people were bandaging my head. There was a lot of shouting. People were trying to console me. I am not sure if I lost consciousness or not. I thought I was dying.

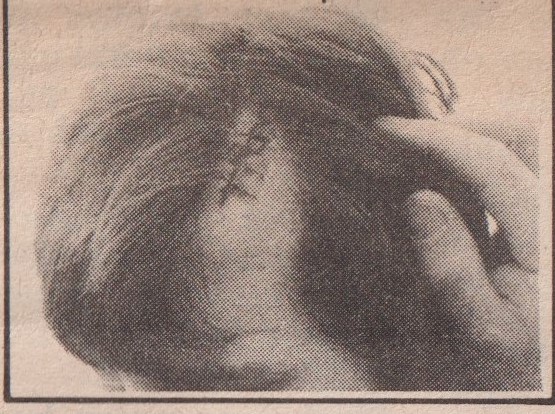

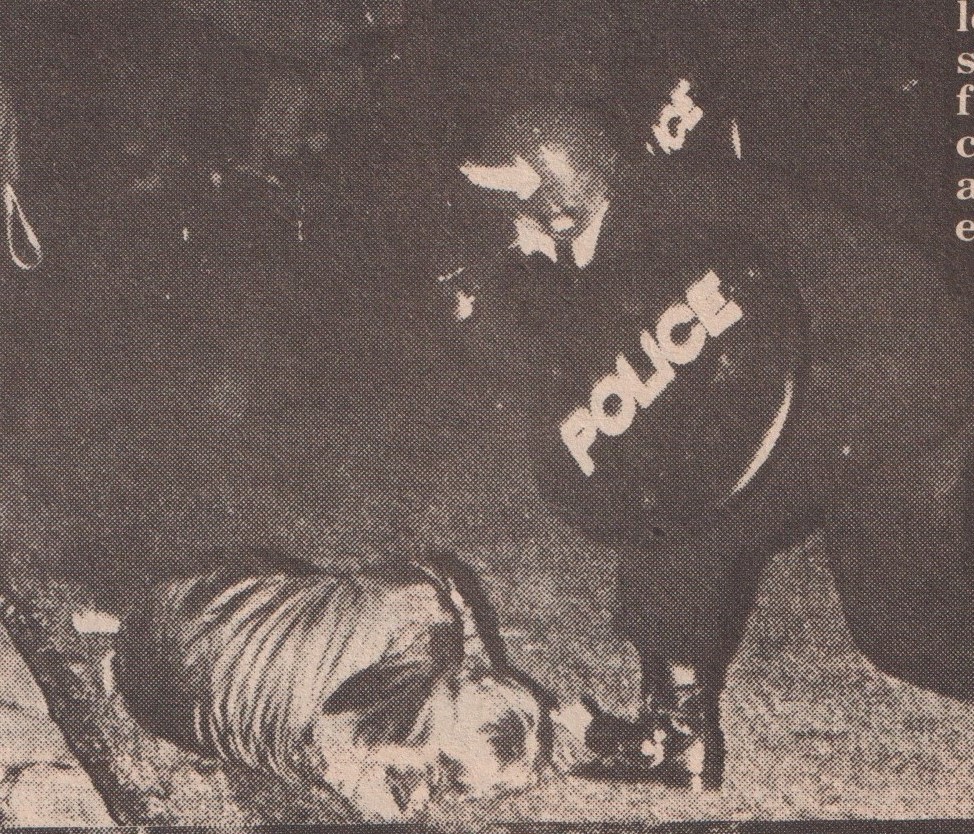

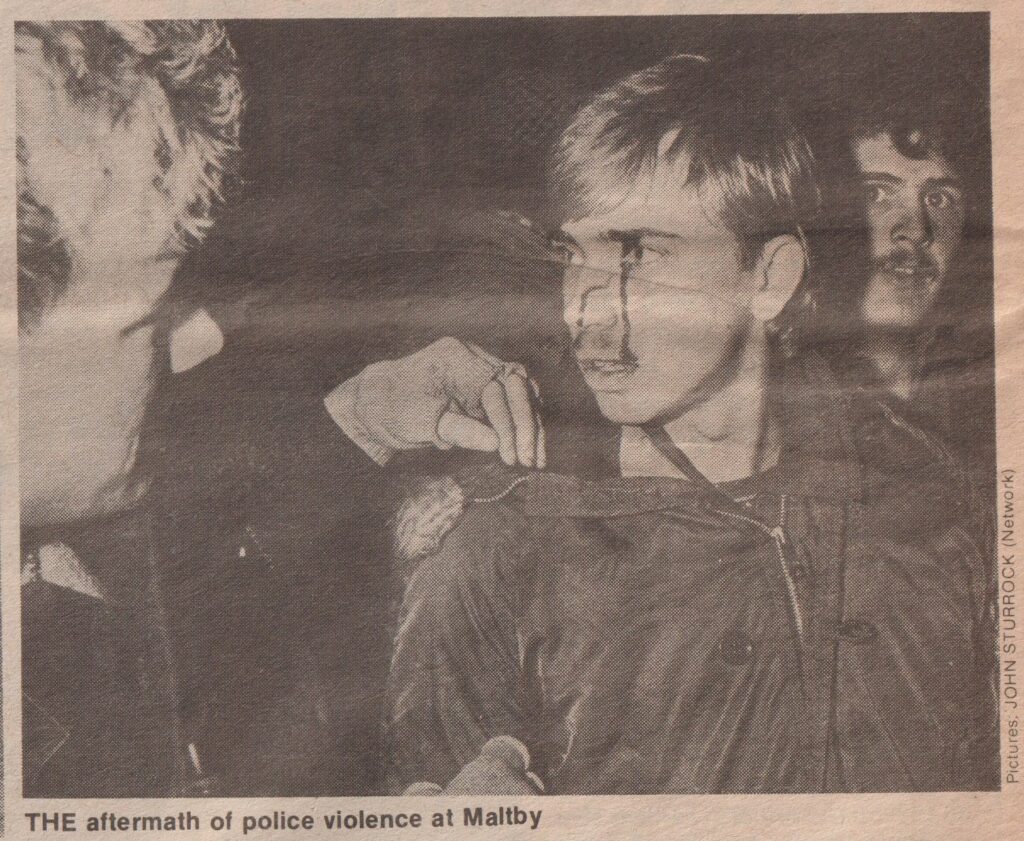

These pictures were taken just after the police attacked me.

I was put into an ambulance and taken to Rotherham Hospital. A man in the same ambulance was also seriously injured. He collapsed in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. Later, I discovered he had kidney damage. Several eyewitnesses later claimed they saw me being kicked and truncheoned by four policemen. I was also told that those miners who had first reached me and attempted to give me first aid were also attacked by the police and had to retreat. It took some time before the ambulance staff could reach me. When I got to the hospital, I noticed other pickets had been brought in and treated for injuries, a few with dog bites.

I received initial treatment from the nurses in the form of stitches to the wound on my head. The nurses were very sympathetic and told me they had only treated one policeman who had a twisted ankle. However, I did not receive a medical assessment of my injuries from a doctor or an X-ray of my head because the police had entered the hospital with dogs and were roaming around the hospital and arresting anyone with injuries. The nurses had no alternative but to usher me and others out of the back of the hospital, where NUM drivers were waiting and I was driven back to Worksop.

When I got back to Worksop, I was still suffering from concussion and sickness with a severe headache and could not walk. The next day George decided I still needed medical treatment and arranged for an appointment with a local GP. George helped me into the back of a van, but on the way to the GP surgery, we encountered a police roadblock. The police dragged George and me out of the van, abused us with obscenities and threatened George. I eventually got to a GP who examined and dressed my injuries, gave me some paracetamol, and wrote a report of my injuries.

I later found out that some of those arrested at the hospital were charged with a range of public order offences including riot. Both Andrew Platt and Mick Wheatley pictured below, were arrested by the police while waiting for treatment at Rotherham hospital. They were then confined under curfew in their houses from 9 pm to 8 am to prevent them from joining early morning pickets.

London

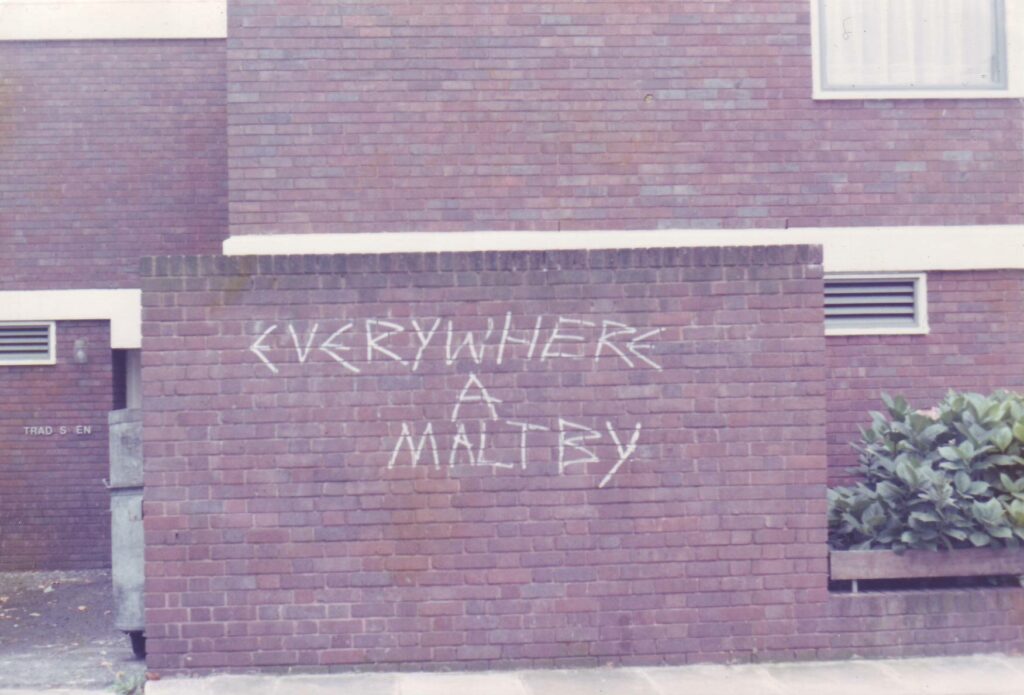

When I was well enough, I returned home to London where I spotted this graffiti on a wall in Kilburn.

On 25 September Malcolm Pithers’s coverage of the events on the Monday at Maltby in the Guardian was similar to the other papers and the BBC. He ignored violence by the police and emphasised violence from the pickets. He claimed that fourteen policemen and only three pickets were injured. However, he reported extensively on Kevin Barron’s bruised arm and also mentioned that Colin Baker an ITN journalist was struck on the head. It is hard to know if this is just lazy reporting and poor journalism but we do now know there was a huge amount of political pressure on the media to back the government and the NCB.[15]

When I was well enough, I was determined to try and contact sympathetic journalists to counter the propaganda offensive by the government and its supporters in the press. I headed to Fleet Street with photographs and a personal statement of the events at Maltby. Not surprisingly, the right-wing press was hostile, but I did not expect the same reaction from the Guardian, which told me that they were not interested and asked me to leave the building. In December, they published the photograph of me taken by John Sturrock on the centre page of the magazine of their sister paper the Sunday Observer to highlight so-called picket line violence without any context or explanation of what happened.

Statement by Ray Collingham

The media claimed 5000 pickets had attacked the police with catapults and airguns. They reported 3 pickets and 14 police officers injured. We saw no airguns and just one young kid with a catapult. There were less than 1000 pickets around when the police attacked them. At least 20 pickets were injured. One policeman suffered a twisted ankle.

I travelled in the ambulance with Ian and an injured miner to Rotherham District Hospital. The injured miner had a broken hand from being hit with a truncheon. During the journey he collapsed; subsequently, I learnt that he had sustained kidney damage from the beating he received.

While waiting in the hospital I saw and spoke to other casualties who were brought in from Maltby, they included:

- A 50-year-old miner who had been beaten around the head.

- The local M.P., Kevin Barron, who suffered bruising to his arms.

- A young miner who had a bad dog bite on his right calf. He was arrested at the hospital; the police demanded £1.60 to pay for a prescription for his antibiotics before being taken away.

- Another young miner, who was also arrested, had 4 stitches put in a head wound before being taken away.

- A Belgian Steelworker who had come over to visit the miners had been bitten on the arm and thigh and beaten around the head.

- Later that day I met another young miner who had been set upon by 5 police and a dog. He lost two front teeth and sustained a black eye and extensive bruising on his body.

- There was one police officer who had been brought in with a twisted ankle. I saw the lunchtime news that day. Part of the film showed him tripping over during a police charge.

Statement by photographer John Sturrock in The Tribune 5 October 1984

John Sturrock estimated that between 800 and 1,000 pickets were standing along the road when the police made their first charge:

There was some sporadic stone, nothing dramatic certainly no air guns, when the police snatch squad charged from behind the floodlights a few times. The photograph of the man lying in the road shows a lad who fell over running away during the second charge. The policeman leaning over him had a truncheon and hit him several times, on the body I think. When the police retreated back, they left the injured man lying on the ground, his face cut where he had been kicked and his body bruised. [16]

Shortly afterwards, Sturrock witnessed the third attack on pickets, but this time the police employed different tactics, charging from behind:

A squad of policemen, their faces obscured by helmets and their blue boilersuits without any means to identify them, emerged from woods at the side of the road near the rear of the pickets. Although there had been some stone-throwing, these pickets were not involved. Many were older retired miners, some were from miners’ support groups and among them was Labour MP Kevin Barron. The police charged regardless into the crowd, which scattered in front of them, with many trying to escape by climbing a wall and diving into a hedge-row on the other side of the road. When the road cleared, Barron was left nursing a badly bruised arm and three or four bodies lay motionless on the ground having either fallen or been knocked down by truncheon-wielding police. [17]

Statements from Maltby NUM Branch Officers

Frank Slater, who was arrested earlier on in the strike in March, said there were:

Lads with broken arms, head wounds needing stitches and hospitalisation. Some were arrested in hospital. One lad was truncheoned by one copper and then kicked by others. He was on the floor and could have easily been arrested without violence. But he wasn’t arrested. It’s quite obvious these police support units are out of the control of their superiors. The police were determined that they were not interested in arresting people. They were just determined to give the lads as much hammer as they could. They injured several of our members, some of them seriously while making no attempt to arrest anyone. Lads were getting hammered on the road and then left on the road. The tension was unbelievable from the beginning, with shield-beating etc. I’ve said from the start of this dispute that the police can only justify being present by creating a violent situation.[18]

Ron Buck: Maltby NUM branch secretary

Buck said “There was blood all over the place” and condemned police exaggeration of the number of pickets as a ploy:

to justify the police using whatever numbers they wanted. If there were 6,000 pickets (the official police estimate), we’d have been stood six miles away. The maximum possible on that day would have been 2,500. After the strike-breakers went into work a squad of police burst out of the wood and went at random beating people with truncheons. It was a sadistic pleasure these people were getting out of this. One lad was left bleeding profusely from wounds on his face, after he was beaten about the face with truncheons, by a squad of police. The pit ambulancemen who were bent down giving him first aid were then clobbered. All the relationship established before the strike has been shattered. Management have put their loyalties behind a few men who aren’t even their employees, as against men who have given their loyalty to the pit, and the community who have been behind it. The branch feels that we have been betrayed to promote strike-breaking by men other than coal board employees. [19]

But Ron was at pains to point out that about 50 Cementation workers at Maltby were supporting the strike, in contrast to the half-dozen crossing picket lines At a packed branch general meeting, which unanimously supported the union’s case and resolved not to return to work with the strike-breakers, the group of Cementation workers supporting the strike announced they would go back only with the rest of the branch:

This has united our branch. They are more resolute now than ever. I’ve never been so proud in my life to represent those lads at Maltby. I’ve dealt with hundreds of cases where families have nothing, but there’s not one of them said they intend breaking the strike. The branch feared that the behaviour of the police would lead to a repeat of clashes in the community experienced earlier in the strike. There’s a housing estate next to the pit with children and old people and we’re concerned that they should be able to live in peace and quiet. But if any troubles come about, the blame should be laid squarely on the coal board. [20]

Ted Millward: Treasurer of Maltby NUM.

There was a massive police presence and we couldn’t get near the pit gate. They shoved us right away to the perimeter of the village. There were some stones thrown, but very little. Police waited until around 250 pickets remained before boiler-suited officers with no identification marks emerged from woods, to launch a savage attack from behind. I was involved at Orgreave, but I’ve never seen anything like this. And a lot of the public, who were on their way to work, saw it all. They saw them smash pickets with no attempt to make arrests. They let their dogs bite us. A journalist was bitten three or four times. One of our first aiders who was bandaging a lad bleeding on the floor was hammered. The police have adopted the tactic of terrifying or injuring our lads.[21]

Bob Mounsey: A 50-year-old Maltby miner and former NUM Branch delegate.

I’d just walked back to the Maltby bus stop to let my wife know I was okay. She’d seen the aggro earlier. As I walked back past the Lumbley Arms, about 35 to 40 police came out behind me. `I dodged two, one who struck at my head with his yardstick and another who tried to knee me between the legs. Then I was hit on the hip. It paralysed my leg. As I stumbled another hit me on the leg and head. `A group of them kicked me on the floor. I’ve got bruises across my kidneys, down my left leg from the hip to the knee, on both shoulders, and there’s a lump on the back of my head. I wasn’t knocked out. I just lay there dazed. An old chap came across to see if I was okay. I tried to get up but he told me to stay down because the police were still hanging about. The police had no intention of arresting anyone. It was just a commando raid to dish out some hammer.[22]

Ronald Jeffery: A Maltby supervisor and NACODS member (Newsline report)

Police wielding batons at Maltby in Yorkshire yesterday behaved like animals. I arrived at the Lumley Arms at the rear of the picket line at 6.15 in the morning. Everything was quiet and the pickets were dispersing. I sat on the wall and watched the men start running up the road and I wondered why. This was the very first time I’ve ever approached a picket line in the strike. Then I was amazed to see figures appear out of the woods carrying batons and shields. Not knowing how many more were going to pour out of the woods, or what was going on, I was very frightened — and I mean frightened. So I ran with the crowd.

I returned to the scene shortly afterwards and witnessed batons being wielded in an animal fashion. The police were not satisfied with flashing their truncheons — they had one guy on the ground with his head already open and were laying the boot into him. An ambulance was held behind the police cordon and the police wouldn’t let it through. It eventually was able to treat him, and I was amazed to see another ambulance arrive from the other direction within the next three minutes.

There were no stones or bottles being thrown prior to the police coming out of the woods. I doubt very much if they were police. They came out like animals — either drugged or crazed through some other fashion. Before the animals appeared the pickets were simply standing and talking and were ready to disperse.[23]

Excerpts from Life on the Front Line: Bruce Wilson’s diary of the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Thursday 20 September 1984.

At Maltby we parked in the Lumley Arms pub car park and walked down the road to the pit. At either side of the road, it was heavily wooded and every now and then there was a length of low stone wall. When we got to the pit entrance, the entire road was blocked by a wall of pickets. It was quiet, no trouble.

The scabs went in from the Tickhill end of the road. Ten minutes later the police lines moved forward pushing us back up the road, and woe betide anyone falling behind. Made our way to the Baggin’ for some snap and a nice cup of tea. I found it hard to believe all these horror stories about Maltby after this morning. It wasn’t too bad.

Friday 21 September 1984 from Life on the Front Line

On the front line at Maltby, our last port of call this morning, me, Daz and Bob were in the woods passing out wood, trees, anything we could move and passing it out to other pickets who were constructing a barricade in the road. The police commanding officer who was stood behind his men on the front line gave instructions to shine a bloody great searchlight on the pickets. It blinded us all, he’s been doing this for a while now. They could run out and batter you, and you would not even see them coming.

But I’ve got an idea. The police would not come nowhere near the barricade, it was pitch black, woods on either side of us. They weren’t daft. We kept the police at bay for a couple of hours. Then they decided enough was enough. They’ve got a new toy, a Transit van with ‘wings’ a large wire mesh guard extending from the van’s front doors. The van drives slowly in the road towards us and behind the ‘wings’ police hide with truncheons drawn, usually with no identification numbers on their boiler suits. Their job is to clear the road and disperse the pickets.

I’m getting rather fed up with all this running about, chased all over risking life and limb, or if you’re lucky just a bit of truncheon and arrest for a pound a day! I’m not complaining though, we are making the police get up early as well. On the picket lines after the scabs have gone in they just want to go back to their nice warm beds and we won’t let them, they hate it when we hang about and they do everything possible to get rid of us. Good day today, we gave them something to do.

A quiet morning. We all got back to the Baggin’ safe. To enjoy what was on offer on the new menu. Over the weekend two C.I.D policemen went in the Chinese takeaway in Maltby, it was full of Maltby lads who beat them up. They got in their car and drove off and came back with a couple of reinforcements. They all got another good hiding.

Monday 24 September 1984 from Life on the Front Line

We made our way back to the car and headed for Maltby. I parked in the Lumley Arms pub car park. Full crew again today. We set off walking to the pit entrance. It was still early morning and pitch black, not very well lit here either, both sides of the road are heavily wooded, the closer we got to the pit entrance, the darker it got, no street lights.

I had in my possession some polished aluminium plate, about 3 inches square and polished to a mirror finish. I dished some out to the lads and saved a few for myself. We had not been on the picket line long, there were a few hundred pickets here now and as expected the commanding police officer ordered his men to put that bloody searchlight on us. It’s terrible, it blinds you. Anyway, he’s had a good run, our turn now. I told the lads what I was going to do. We all pointed our polished plates at the searchlight and it worked! He switched the searchlight off! He turned it on us again, we showed our mirror, and he got the reflection back. After a few more goes with his spot lamp he gave it up as a bad job. Ha Ha, those few hours in the shed making them paid off.

It was still pitch black and quiet on the front line, row-upon-row of police in front of us. We turned round and there were hundreds of miners behind us. About ten foot away from me, Razzer [Silverwood lad] shouted,”WERE HAVING A PUSH, SO ALL BADGE COLLECTORS GET TO THE BACK,” there was roars of laughter.

Then a reply came back, “WHAT THA’ FUCKING ON ABOUT’ I’M HERE AREN’T I?” When the laughter died away someone shouted ‘Zulu’ that was it, all the front line pickets ran at the police lines (the distance between the police and miners’ was only ever a few feet, just enough distance to stop them reaching out and snatching you). Pushing and shoving against the police lines, a couple of lads next to me went down on the floor. This went on for about five minutes and the police don’t like it at all!

Several lads on the front line were ‘snatched’ and arrested, they disappeared into the dark behind police lines. Things heated up then, from the back of the picket line a few stones and missiles went over into the police lines, It went quiet again, then some more missiles were thrown into the police ranks. That was it, they charged, the first one of the day. I ran back up the road, but I could not get past the mass of pickets in front of me, so I jumped over a small wall, right into the laps of two riot police knelt down hiding, batons drawn, wearing boiler suits with no numbers on. They looked as surprised to see me as I was them. They did not get me, but nearly.

I met up with Shaun back on the road, it went quiet again, we were about 30ft from the police lines. We decided to have a look around and try and sneak round the police. We went into the woods across from the pit entrance. We had only gone a few yards when Shaun shouted to me ‘look at them rabbits’ we could see pairs of eyes looking at us in the dark. They were all over. The thing was, the eyes were about 3ft off the ground. We just saw the dog handlers in time. Retreating in the dark, I said to Shaun, “big bloody rabbits them mate!”

We made our way to the front line again. We stopped for a while, but then and I don’t know why, decided to go back to the ‘Battle Bus’ for drink out of my flask. We usually stay until the last. All the crew decided to go back with me. We were sat in the Lumley Arms car park supping tea when all hell broke loose, miners came running back up the road towards the village. We got out of the car and set off walking back to the pit entrance. We could see within spitting distance the police had done a dirty trick. The boiler suited ‘snatch squads’ had gone into the woods on either side of the road, sneaking around the pickets in a pincer movement. Then they came out of the woods, back onto the road, trapping about thirty pickets. They were cut off and surrounded by riot police and nowhere to go! Dogs and their handlers were still in the woods. The poor bastards, the police went wild and truncheoned anything that moved.

Big bastards they were, not one under 6ft 4in. Yellow jackets on, no identification numbers. Police? More like the Coldstream Guards on manoeuvres. We came across one lad unconscious with a fractured skull, blood all over the place, a copper was stood on him while three others laced into him. A man went to help him, a copper grabbed him and threw him to one side, the copper told the man to leave him and “fuck off”.

Riot police running about all over the place with no numbers on. Same old story of pickets treated like criminals. Walking back to the car we passed Kevin Barron the Rother Valley MP. He was making his exit as well, he looked rough, looked like he had some boot and a bit of truncheon for good measure. The police grossly exaggerated what went on today. Their purpose is to slag the pickets down so they can get their ‘rubber bullets’.

November Fire and Fury

Tensions in Maltby escalated further and resulted in serious rioting in November. The papers reported “A night of Fire and Fury” across the South Yorkshire coalfield on Monday 12 November. They reported that ‘mobs’ had attacked police stations, looted shops and set buildings on fire and coalfield violence reached new peaks of savagery. The papers claimed petrol bombs, spears, metal staves and six-inch bolts were hurled at police, as the violence spread from pit gates to mining villages. They quoted a police spokesman who said: “It has been the worst night of violence we have had since the strike began. It has been coordinated throughout the county and not concentrated at one pit, which has previously been the pattern.” The Liverpool Echo said:

Pickets began gathering in the county shortly after midnight. It was seven hours before calm was restored. The first trouble came at Maltby at 2.45 a.m. when the police station came under siege. Several windows were smashed as missiles rained down on the building. On the A631 between Maltby and the colliery, a workman’s cabin was dragged into the middle of the road and set on fire. Pickets uprooted lamp standards to obstruct police vehicles. Wires were strung across the road at head height. A garage was broken into at Maltby and looted. Oil and glass covered the road near the colliery gates.[24]

The Times reported that at Maltby street lamps were pulled down to form barricades and by the end of the morning, trouble had occurred at over half of South Yorkshire’s collieries leading to 45 arrests, 33 police injuries and 9 pickets injured.[25] However, given the distortion in reporting the events at Maltby in September, the accuracy of these reports must be viewed with caution.

Hammersmith and Fulham Miners Support Group

I kept in close contact with George and Christina during the last six months of the strike and returned on several occasions, once to appear as a witness in the court cases which followed the Maltby picket. I also continued to work with colleagues in the Hammersmith and Fulham Miners Support Group organising events and fundraising.

HFMSG was twinned with Sutton Manor Colliery in Lancashire (which closed in 1991) and regularly organised events and street collections. It was infiltrated by a Sun journalist. The group was informed by print workers at the Sun about his infiltration. Consequently, he was deposited on the motorway for his safety while on a trip with members of the HMFSG to Lancashire to visit Sutton Manor. He then wrote an article which was published in the Sun which was full of lies and distortions about the miners of Sutton Manor and the work of HFMSG.

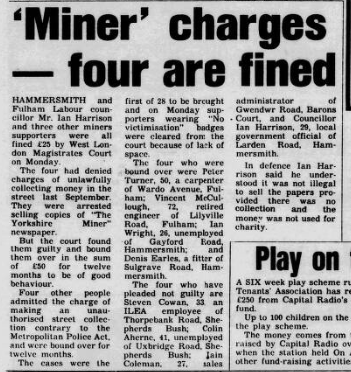

In October 1984 some HFMSG members and charged with selling copies of the Yorkshire Miner without a street licence. These included Peter Turner, Vincent McCullough, Ian Wright, Dennis Earles, Steven Cowan, Iain Coleman Colin Aherne and Ian Harrison (both Labour Councillors). They were all found guilty and either fined or bound over.

Thousands of miners and their supporters were arrested during the strike including George Bell and either imprisoned, fined or bound over to keep the peace. This was an effective way for the authorities to prevent picketing and fundraising and so undermine the strike.

Return to Work at Shireoaks

At Shireoaks, where 920 were on strike, several men returned to work in early October. Picketing and maintaining solidarity were tough during the winter months and by mid-November, the papers reported that 43 miners had returned to work at the pit.[26] However, in contrast to the rest of Nottinghamshire, Shireoaks and Manton NUM had persuaded NACODS members not to cross their picket lines, which meant no workers could go underground because of statutory safety rules.

At the end of December, the papers were reporting that 600 miners had returned to work at Shireoaks, amounting to 74 per cent of the workforce but that NACODS members persisted in refusing to cross the picket line, so the 600 men who had returned to work could still not go underground but had to be paid by the NCB.

However, at Manton Colliery, coal production started for the first time in nine months on 1 January 1985.[27] The next day, on 2 January 1985, some deputies crossed NUM picket lines for the first time at Shireoaks. At this time, 906 men were at work at Manton and Shireoaks.[28] By the beginning of February, 76 per cent of the workforce was back at work at Manton and 80 per cent of the workforce was at back at work at Shireoaks Colliery. [29]

On 12 February a High Court judge banned mass picketing at the following Yorkshire pits; Rossington, Maltby Riverton Park, Allerton, Bywater, Frickley, Yorkshire Main Wath-on-Dearne, Manton, Manvers and Shireoaks The orders were made against the Yorkshire area alone and injunctions forbid the Yorkshire area organising more than six pickets at the gates of 11 pits at any one time.[30] This ruling meant that there was little hope that striking miners could do anything to prevent miners from returning to work in areas where support for the strike had weakened.

The Heart and Soul of It

Picketing was important but the solidarity required to keep the strike going was also sustained by the action of those in the pit villages and communities, often women, who organised soup kitchens, looked after children and kept households functioning. Some miners’ wives were involved in fundraising, joining pickets, meetings and demonstrations. However, some also worked, providing an essential income for the household as well as performing domestic duties, which limited the time they could spend on strike activities.

The following extract is from: The Heart and Soul of It, A documentation of how the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike affected the people in the pit village of Worsbrough and surrounding districts, and of their survival. It was published by the Worsbrough Community Group and Bannerworks in May 1985. The section on Shireoaks printed below describes the last months of the strike in Worksop and Rhodesia, a nearby small pit village for Shireoaks miners and the visit there by some women from Worsbrough.

Worsbrough Community Group visited Shireoaks Pit and the Rhodesia Women’s Support Group on 15 February 1985. We found some of the striking miners in the miners’ welfare which is across the road from Shireoaks pit. We spoke to George Bell, who is the branch president for the pit. He told us:

This particular colliery is called Shireoaks/Steetly colliery. It’s called that because recently Steetly Pit was merged with Shireoaks. Some may say that the local pit (Steetly) was closed, but officially it was classed as a merger. There used to be 500 workforce at Steetly and just less than 800 at Shireoaks; the combined workforce is now 920, and of that 920 there’s about 820 NUM members. Geographically we’re in Nottinghamshire, but we’re in the South Yorkshire area, the pressure has been on both our pit and Manton pit ever since the strike started.

The original two scabs went in to work on the 3rd of October, they were complemented by some more on the 15 November, and then there was a flood when the local village went in shortly after, that’s Rhodesia village. It’s been a steady trickle since then until it reached a peak just before Christmas. The NCB class people who are on sick as working, so they say the actual number of working miners is 660. This leaves us in the region of 140-50 on strike. We live in and around the area of Worksop and socially there tends to be a lot of tension, particularly when you go out for a drink or when you go down the main streets. We’re not so bad, the people who have it really bad are the people who live in Rhodesia village where 97% of the workforce are working.

NACODS went in to work on one shift after the New Year, because we didn’t have very much of a picket on, since then we’ve managed to counteract that by having a decent picket on and also by asking NACODS to adhere to 1974 guidelines, which they have. The men who are working can’t go down the pit without NACODS so they just mess around on the pit top. We’ve been told unofficially that it’s costing the coal board an estimated 1/4 million pounds every eight to ten days since the 15th of November, in workforce and materials, yet no coal is coming out. This was supposed to be a very economic pit, but it’s actually an uneconomic pit now. In the last two years before they closed Steetly, they spent 36 million pounds on Shireoaks, building a new drift etc and putting the idea over that it is a safe pit, if there is such a thing.

The scabs have now got a bit of confidence and have started coming to our meetings. We think their tactics are that they want us back up at the pit as a union. As things are now they’ve got no negotiating power, management can do what they like with them. They want us back up there so they can get some negotiations going over agreements. They may try and put pressure on us through general meetings. All the branch officials are on strike, but we had three treacherous committee men who broke the strike in the early stages. In fact one of them didn’t even have the guts to resign, he’s only just handed in his resignation now, in case we threw it at him at the general meeting.

Two Songs, sung to us by George Bell of Shireoaks:

When me father was a lad

Unemployment was so bad

He spent best part of his life

Down at the dole.

Straight from school to the labour queue

Ragged clothes and holey shoes

Combing pit heaps for a mankey bag of coal.

CHORUS

And I’m standing at the door

That same old bloody door

Waiting for the payout like me

Father did before.

Nowadays they’ve got this craze

For all these clever monetarist ways

And computers measure economic growth

We’ve got experts milling round

Writing theories about the pound

But no one tells me just how I can buy a loaf.

CHORUS

Harold Wilson, he took charge

Half a million got their cards

And he said it was because his party had got soul

Then along came Grocer Heath

With his concertina teeth

And he put another million on the dole.

CHORUS

Then Thatcher came along

Oh the Falklands made her strong

She was determined that she’d bring us to our knees.

So we had to be content and accept unemployment

And no one ever seemed to listen to our pleas.

CHORUS

One day don’t be surprised

When the miners get organised

Politicians will start to tremble at the knees.

For we’ll march on Downing Street

As we rally with our feet

And for once they’ll have to listen to our pleas.

For we’ll be kicking down that door

Oh that same old bloody door

We’ve waited for our payout a million times before.

Kicking down that door, that same old bloody door

We’ve waited for our payout a million times before.

The pit that I used to work at up North like, is called the Rising Sun, but it closed down in 1969. This song is called ‘The Fall of the Monty’, which is the Montague pit and a lot of the Montague pit lads came to the Rising Sun to work, and when that closed they adapted the words to suit.

For many long years now

They’ve tried so they say

To cut out the losses

And make the pit pay.

When all of the rumours

That closing was due

Have all been put down

For alas it was true.

We met our officials

And reporters galore

For the pit it was dying

And we wanted war.

But all of our arguing

Still nothing was done

We had to admit it

They’re closing the Sun.

I’ve worked in the G pit

In the Brockle seam

I’ve worked in the Beaumont

Since I was Fifteen

I’ve worked in the Busty

And in the Main Coal

No more to you Rising Sun

You dirty black hole.

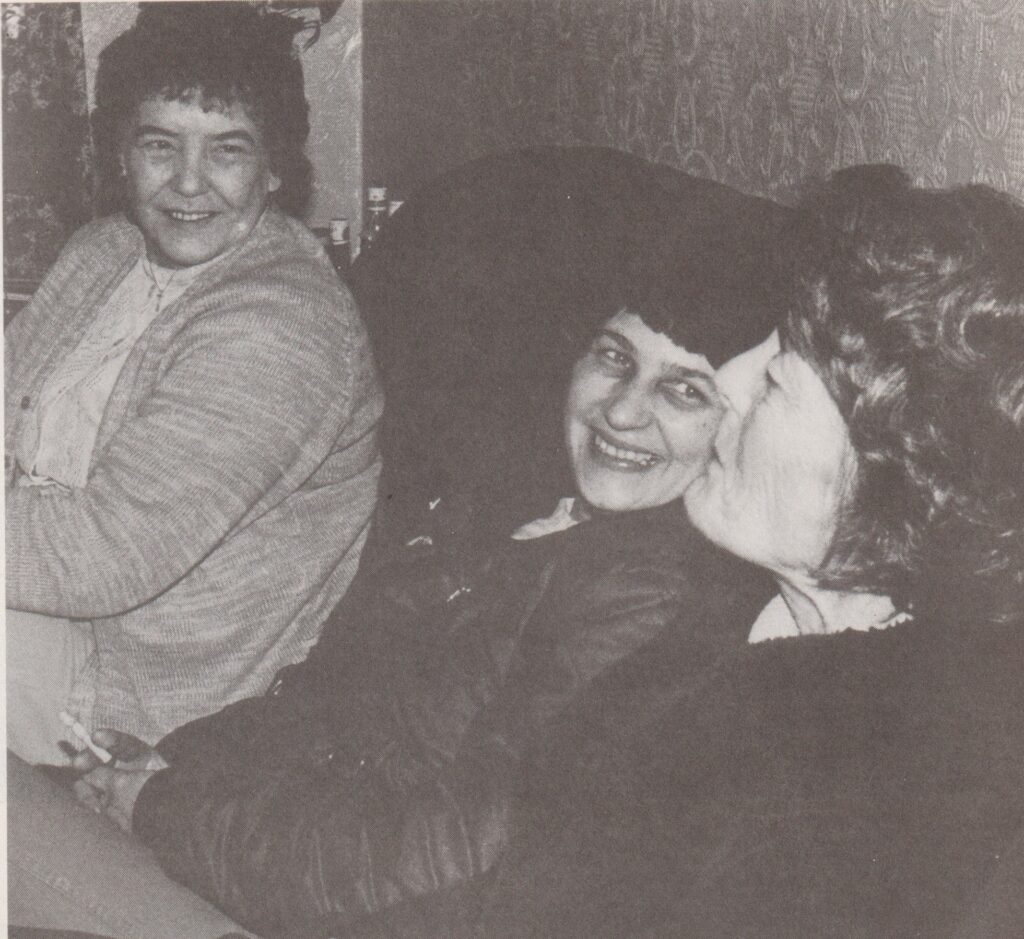

Rhodesia Women’s Action Group (Pit village for Shireoaks near Worksop)

In this village, striking miners are very much in a minority. We spoke to six women who have been involved in the women’s action group from the start of the strike. We began by asking them how they are regarded by the majority of people in the village who are against the strike. They told us:

There are only 14 families left on strike in this village. We had 13 women in the action group to start with, now we are down to 8. Being on strike here is like being sent to Coventry. We can be stood at the bus stop for instance and people walk past laughing and joking and giving us dirty looks. Even the women who used to be in the action group don’t talk to us now. There are people in the village that I’ve known all my life, who walk straight past me, because I’m involved with the action group.

People have never been really solid in this village, although a lot did stay out until November. While ever people needed help and they were on the receiving end they were all quite happy with what we were doing in the action group but as soon as they all went back to work they thought we should join forces with them and get off back to work as well. They didn’t think we would carry on, they were dead mad when we did continue.

When we used to go round to the houses collecting in the beginning people used to say to us ‘Thank you very much, you lasses are doing a good job, keep up the good work’. Now the same people ignore us. When we go in the club we are the last to get served at the bar and nobody will sit near us. Some of the men went on the walk from Worksop to London.

While the men were away we used to go down to the working men’s club and whatever turn was on we used to ask them to sing ‘Walk On’. We would all stand up and sing along and the ones who were against the strike used to walk out.

When all the scabs went in virtually every one of us was in tears, it bloody hurts, it’s very depressing but you pick yourself up and carry on. I can understand that after nine or ten months on strike some people are going to be desperate, but what they don’t seem to understand is, that by going back they are prolonging it for everybody else. If you’re not going to follow your union and abide by union rules and national decisions, then you should not be part of the union in the first place.

The community is not split, there is still a community, it’s just that we’re not part of it anymore. We are treated like foreigners. The kids haven’t been bad with each other, there hasn’t been any fighting between them, not like some places.” We asked what kind of activities the action group have been involved with and what kind of support they have had. “We haven’t done much lately because there aren’t enough of us left. We used to do dinners for the pickets and we did food parcels, which we still do. We did the kids’ school dinners every day during the summer holidays.

We’ve been all over collecting, we’ve had raffles, jumble sales, meetings, everything, you name it, we’ve done it. We’ve been all over the place, places we’d never have dreamt of going like London and Greenham Common. We can’t collect in the village anymore but we’ve got contacts, people who we’ve met up with, they keep sending us cheques.

The Greenham women sent us £195 plus one or two little cheques. We’ve had a lot of support from the East End of London, the people down there haven’t got much themselves and yet they’ll give us all they have, in fact sometimes you feel guilty taking it, because they look as if they need help. We went to London last week, and one old woman who was 86 years old, said her dearest wish was to shake hands with Arthur Scargill. We wanted to write to `Jimill Fix It’ but were told it was too political. We had a word with George, our branch president, he’s going to take a letter to Arthur for us. She probably hasn’t got many years left. Her and her family have been behind the strike all the way, she can remember 1926 you see. “We’ve been on the picket lines, the first one I went on my legs were shaking. It was a women’s picket but the police brought in the meat wagon. They were just grabbing women by the neck and throwing them in the van.

Once we went on a women’s picket to Kiveton Park pit, we wondered where everyone had gone, then someone told us they were all on holiday for two weeks, it was hilarious, picketing an empty pit.” One of the women who had been arrested on a picket line told us what happened. “Look at the size of me and I’m charged with assaulting a police officer. We were all walking up to the pit, the bobbies told us we couldn’t go up but we said we were going to peacefully picket and kept walking. They arrested the first 17, the ones that were in front, then let the rest go up to the pit. My husband was one of the ones arrested so I went running over to him and the police said to me ‘Come on you’re going as well’. It was 10 a.m. when I was arrested, they brought me two slices of bread and jam to eat and a drink about 6 p.m. I was in a cell on my own, the men were all in together. When they released me at 8 p.m. I had to walk past the cell where the men were, they had all thrown their bread and jam onto the ceiling.

I’ve been to court five times since June and it’s still going on. They’ve even changed the name of the arresting officer. The bobby who arrested me had no number on his uniform, he must have been army. “It’s like a battlefield sometimes, they lash out with their truncheons, they don’t care. I always think ‘That’s some mother’s lad’, it’s awful. I’ve been brought up to respect the police but I hate them now. “The police used to watch our houses, you could spot them a mile off They weren’t very inconspicuous. “The police taunt us with how much money they’ve earned ‘£90 we’ve earned today, thankyou’. If Thatcher hadn’t brought the police in there wouldn’t have been any trouble. This strike hasn’t just happened it’s been planned from 1974, give the woman credit, she’s planned it bloody well.

We asked the women how the men reacted to their involvement:

They think it’s great, they’ve been behind us all the way. They have said that they couldn’t have stuck it out without us backing them.

One of the women’s husbands told us:

The women have fought during this struggle not just for our futures but for their own. They’ve realised the point is not just ‘will I have a job tomorrow’, it’s will we have a wage coming into the house. The women have been strongly behind the men. They’ve been bloody marvellous.

We asked the women what they will do when it’s all over:

We hope to carry on with something, I’m not going back to being a bored housewife. There are people that have helped us through this strike who we will be able to help in return. There are the Greenham Common women or the teachers who have a strike coming up soon or there is the South London Women’s hospital that is in occupation. We will have a bit more money when the strike is over so we can go to different places and offer our support.

Retun To Work

–

–

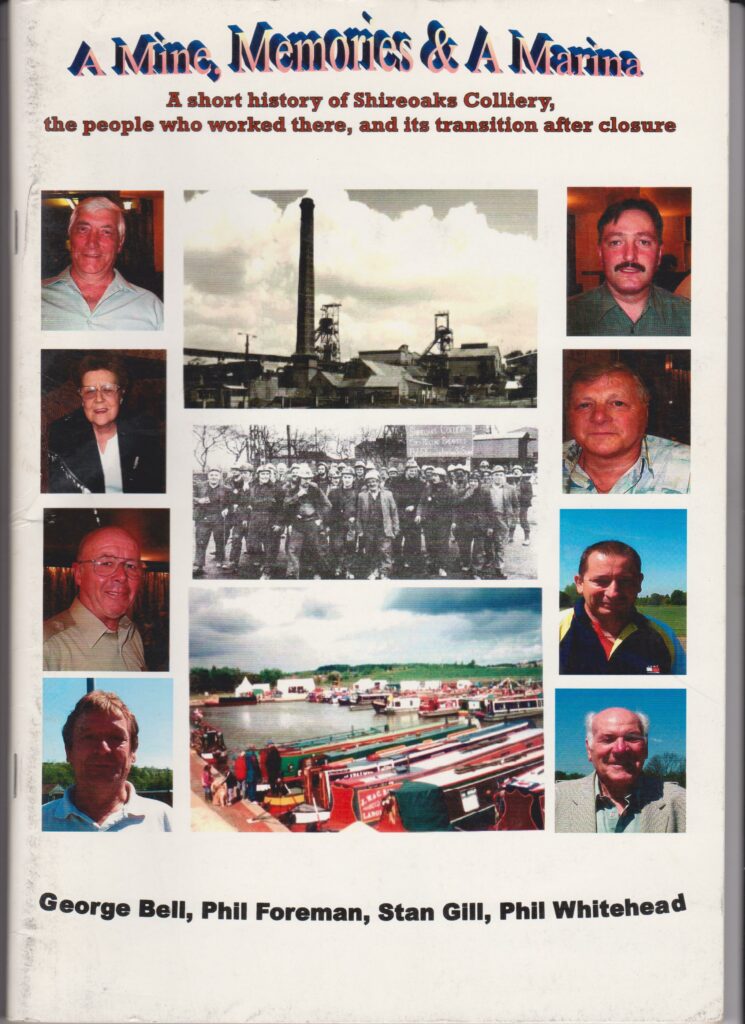

George struggled with the loss of camaraderie after the end of the strike so, after 3 years, he decided to take voluntary redundancy. Shireoaks Colliery finally closed in May 1990 and Manton Colliery closed in February 1994. In the conclusion of the book printed in 1991 (A Mine, Memories and a Marina, a Short History of Shireoaks Colliery, The People that Worked there, and its Transition after Closure), George said:

I started working at Shireoaks on 5th March 1973. At that time the area and the colliery appeared to have an assured future. So much so, that I was offered ‘ a job for life’. In the late 1970s, cash started pouring into the colliery. At Shireoaks/Steetley, somewhere in the region of £38 million was invested in new coal-getting measures, such as the Surface Drift and Coal Preparation Plant. The local Member of Parliament, Joe Ashton, visited the colliery in August 1982. He described it as ‘….a good example of co-operation between the NCB and NUM’. He went on to say that he had been told that the mine had a ‘magnificent future with a minimum of 25 years.

Norman Siddall, then Chairman of the National Coal Board, came to visit the colliery in 1983. At a reception party held for the workforce and management he spoke at length about the ‘bright future ahead’. Moreover, in the same year, George Hayes, NCB South Yorkshire Area Director, described Shireoaks/Steetley Colliery as ‘the jewel in the crown of the coalfield’. However, things were soon to change. The catalyst being the 1984/1985 strike. Rumours were rife from 1986 onwards as to imminent closure. Each set of rumours seemed to weaken morale a little more each time. Finally, closure was announced in 1989.

In my opinion, it was a callous, calculated political act, which took no recognition of the effects on the area. As one resident said at the time ‘the heart has been ripped out of Worksop’. Without doubt, there have been dramatic changes to the lives of the ex-workforce of Shireoaks/Steetley Colliery since its demise. This has had a traumatic effect on some individuals. Moreover, the closure has had economic and social consequences for Worksop and the communities surrounding the colliery. During the late 1980’s and early 1990’s collieries were closed with great haste. There seemed to be a political desire to make sure that any sight of any coal mines that were closed was quickly taken away from view.

After leaving the pit George studied for an HND in public administration and then an urban studies degree at Hallam University. His thesis was called Coal, Community and Camaraderie which examined the social and economic effects of pit closures. He discovered that out of the 71 former Shireoaks workers interviewed, only 62 per cent were in employment in November 1992 and 80 per cent said they were worse in terms of income. Many of them had fewer friends and missed the comradeship of the mine. His dissertation ended with the words:

What is certain is that the events of the late 1980s have seen the end of an era. For coal, camaraderie and community things will never quite be the same again.

https://www.lincolnshireworld.com/news/video-ex-miners-march-to-re-live-dark-days-of-miners-strike-at-shireoaks-colliery-2238080

https://www.lincolnshireworld.com/news/video-ex-miners-march-to-re-live-dark-days-of-miners-strike-at-shireoaks-colliery-2238080

George obtained a job as a homelessness officer with Bassetlaw District Council and soon became the UNISON branch secretary. In 1997 he was seconded to work in Harworth Derbyshire where he had been arrested in 1984 while picketing. He said, “I was shocked at the illiteracy rate; people couldn’t fill out their housing benefit forms and so were being evicted.” George is now retired and spends his spare time helping to renovate the local canals.

The miners at Maltby Colliery were the last to return to work when the strike ended. In 1994, the pit was sold to RJB Mining (later known as UK Coal), and in 1997 to Hargreaves Services. Maltby Colliery closed in March 2013, with a march held by former miners and residents of the town to mark the occasion. The Miners’ Welfare Institute closed in 2018.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-22051348

Timeline showing key dates 1984 – 1985

Late 1983: National Coal Board announces its pit closure programme. It later announced an accelerated closure programme – a process which would take just 5 weeks to implement for some pits.

5 Mar 1984: Cortonwood miners walk out on strike following a ballot.

12 Mar 1984: The various local strikes were declared.

19 Apr 1984: Following a Special Delegate Conference at Sheffield the NUM calls on all of its members to come out on strike.

18 Jun 1984: Major battle between striking miners and the police at Orgreave Coking Plant, near Rotherham.

19 Jul 1984: Margaret Thatcher refers to the ‘rule of the mob’ and the ‘enemy within’ (the ‘enemy without’ had been Argentina who had invaded the British Falkland Islands two years before).

20 and 23 September: Pickets and police violence at Maltby.

19 Nov 1984: 97.3% of Yorkshire miners on strike.

14 Feb 1985: 90% of Yorkshire miners on strike.

1 Mar 1985: 83% of Yorkshire miners on strike.

3 Mar 1985: NUM calls off the strike.

5 Mar 1985: Miners return to work.

[1] Quoted by Natalie Thomlinson author of Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Natalie Thomlinson

Women and the Miners’ Strike, 1984-1985 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024)

[2] Daily Express 25 September 1984.

[3] Sheffield Morning Telegraph 25 September 1984. Kevin Barron was the Labour MP for Rother Valley from 1983 until 2019. On leaving school in 1962, Barron became an electrician at the Maltby Colliery.

[4] Huddersfield Daily Examiner 22 March 1984.

[5] Nottingham Evening Post 23 March 1984.

[6] Belfast News-Letter Monday 18 June 1984.

[7] The Guardian Monday 18 June 1984.

[8] The Guardian 25 June 1984.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Guardian 15 August 1984.

[11] The Hinckley Times 27 July 1984

[12] Ibid.

[13] Yorkshire Miner, Strike Issue no. 5, October 1984.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Guardian 25 September 1984.

[16] Tribune 5 October 1984.

[17] Tribune 5 October 1984.

[18] Yorkshire Miner, Strike Issue no. 5, October 1984

[19] Yorkshire Miner, Strike Issue no. 5, October 1984.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Socialist Worker 29 September 1984.

[22] Socialist Worker 29 September 1984.

[23] Newsline 25 September 1984.

[24] Liverpool Echo – Tuesday 13 November 1984.

[25] The Times 13 November 1984.[27] Birmingham Mail – Thursday 13 December.

[28] Huddersfield Daily Examiner – Wednesday 02 January 1985.

29] Sandwell Evening Mail – Monday 04 February 1985.

[30] Liverpool Daily Post – Wednesday 13 February 1985.