I started work in the Forest just over 50 years ago. I hadn’t been in the council offices for more than a few weeks before noticing lorries, laden with blackcurrants, going up the hill past the office window. I was already active in my workplace union and within the local trade union council where I had met many committed shop stewards from well organised workplaces, but I can’t remember meeting anyone from the unions at Beechams until they walked off the job in the late summer of 1977. Working with pickets on their marvellous picket line, I spent the next few weeks working my socks off to spread the word about the strike, organising solidarity meetings and collections around the forest and much further afield. When workers at the factory, now owned by Suntory, came out on strike earlier this year, I wrote an an anecdotal sketch to tell the story of the 1977 strike which I circulated and discussed on their picket line. The discussions were fascinating but the dispute was quickly resolved. I believe the Beechams strike of 1977 should go down as an important piece of local working class history. Here’s my memory…I hope you enjoy reading it.

Phil Jones

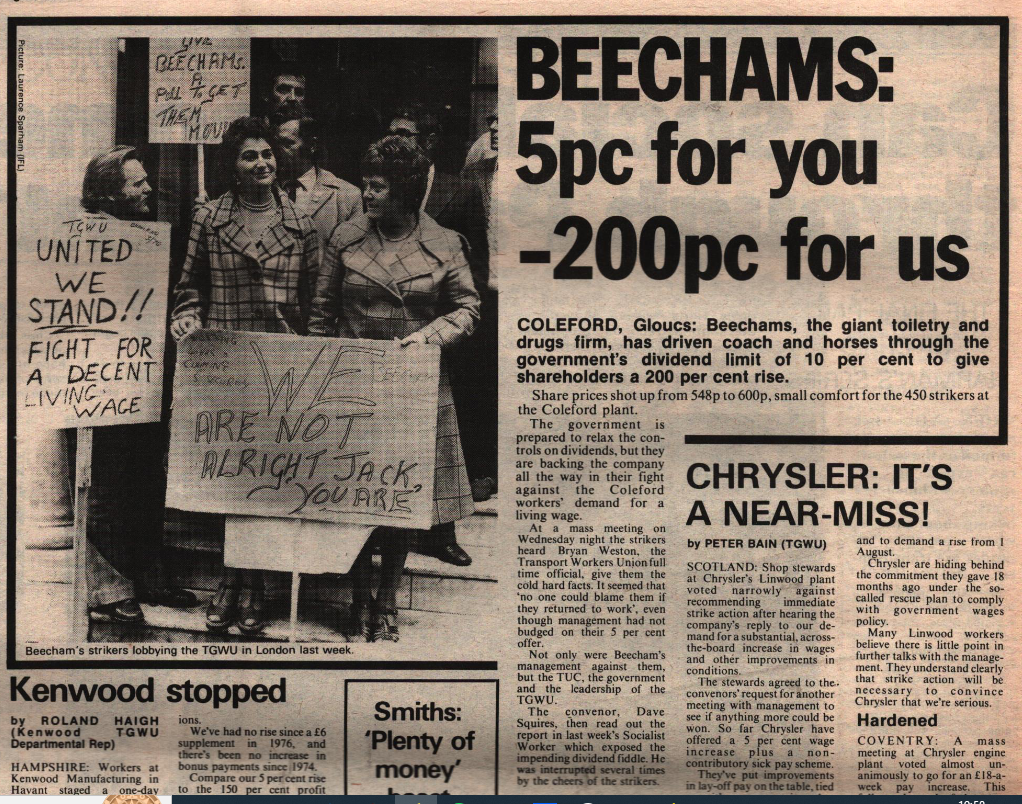

In the late summer of 1977, 450 low-paid workers at the Coleford soft drinks factory came out on strike after Beechams, the giant drinks, drugs and toiletries manufacturer, had driven a coach and horses through the government’s 10per cent dividend limit to give shareholders a 200 per cent rise.

Two years earlier the Labour government and the TUC had made an agreement, the Social Contract, which ‘voluntarily’ limited wage rises in exchange for a promise to improve rights at work and the provision of social welfare. The trades union leaders had held back on wage demands for almost three years but there was rumbling in the ranks as inflation took hold and the cost of living hit wage workers hard, particularly the low-paid. The Transport and General Workers union conference had voted to end wage controls at its conference, a few weeks earlier, but the leadership of the union was not willing to lead a campaign against the Labour government.

The workers at Beechams had other ideas. The workforce, two-thirds of whom were women, was a mix of seasonal, part-time and full-time workers, working a variety of shifts. Most were union members, but few had been on strike before. The convenor proudly wore a CTU tie. He was a Conservative Trades Unionist. He was pressed to call a mass meeting to discuss the annual pay offer and was taken completely by surprise by the result. The workers voted to strike.

Faced with reticent and even hostile trade union leaders the rank-and-file workers stepped up to the task. They elected a strike committee with mainly women in the forefront and organised round the clock picketing at the factory entrance, establishing an atmosphere of determination and good humour. Most workers took picket duty seriously, but it was often a fun place to be. Workers from local factories and offices were welcomed at the picket, which at times resembled a campsite. Women, who made up two-thirds of the workforce, took many of the leading roles but they didn’t need titles or badges as they were leaders who had the respect of their workmates. This was possibly the first strike against the social contract, and they were taking on a multi-national company, the Labour government, and the leadership of their union, who refused to make the strike official.

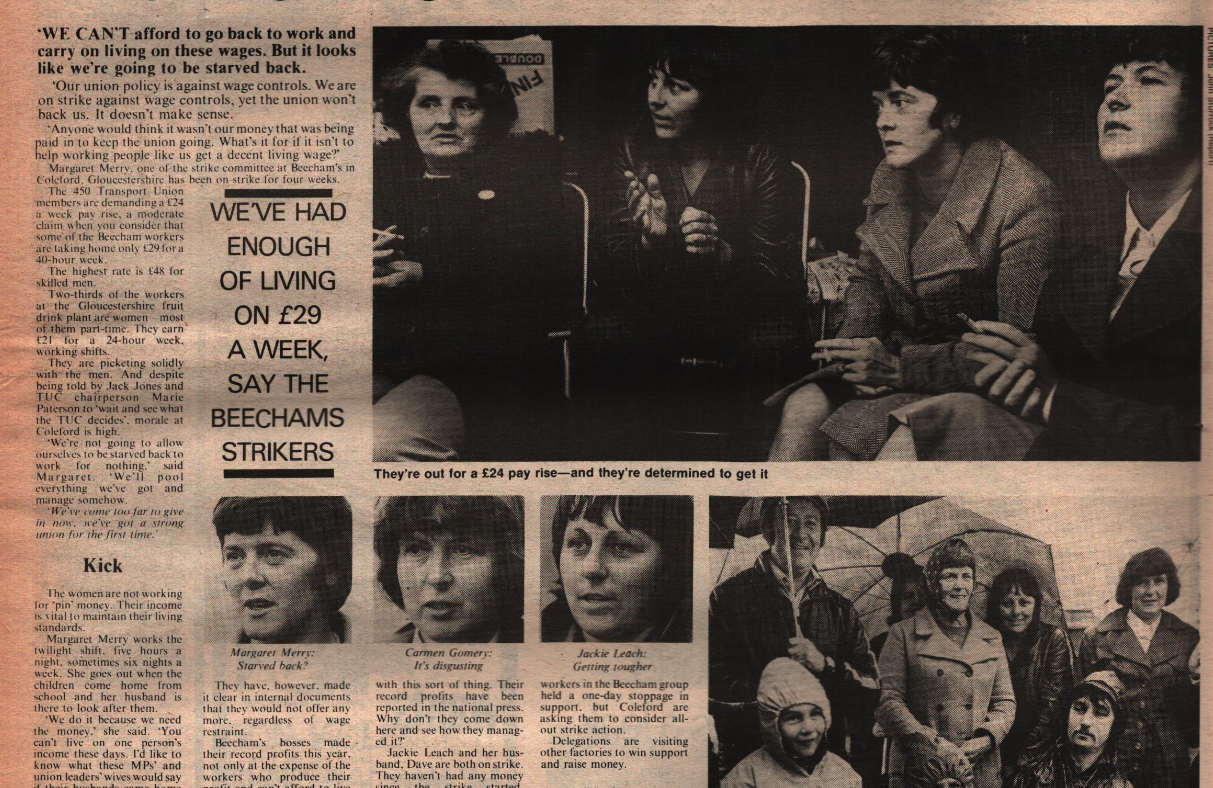

Margaret Merry, a twilight shift worker, told a national newspaper:

We can’t afford to go back to work and carry on living on these wages. Our union policy is against wage controls, yet the union won’t back us. It doesn’t make sense.

Margaret Merry, speaking out against those who argued that seasonal and twilight workers were ‘just working for pin money’ said:

I work five hours a night for five or six shifts a week. I go to work when the kids are back from school and my husband has come home from work to look after them. We work because we need the money. You can’t live on one person’s income these days. I’d like to know what these MPs and union leaders would say if their husband came home and put £30 on the table to keep a family for a week. In thirty years, there’s never been a strike here. The management have got richer while we’ve got poorer. They offer £3 a week. It’s nothing.

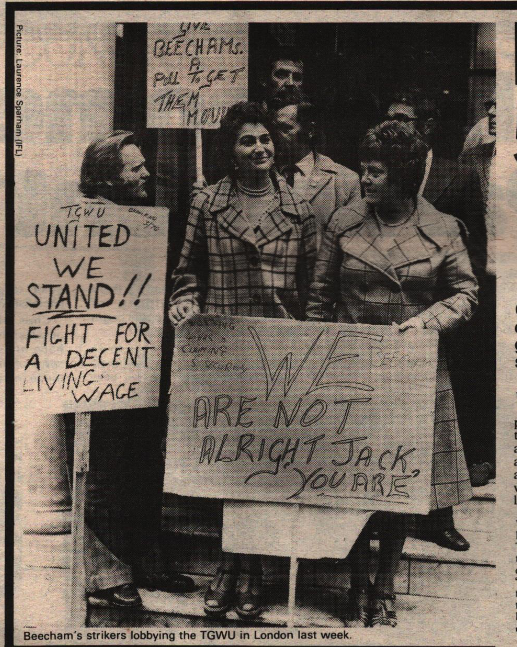

Margaret Merry, Carmen Gomery and Jackie Leach were just three of the women who took a lead during the six weeks they were on strike. All three women, and many more besides, were not only trusted and willing to give a lead to the Beechams workers; they were willing to stand up and draw in support and solidarity from workers in the Forest of Dean and further afield. They organised a lobby of the TUC conference and a solidarity meeting of 60 trades convenors and shop stewards from factories and other workplaces around the forest and Monmouth. Money started coming into the strike fund from collections and donations, but the Transport Union refused to make the strike official.

When it was suggested that they travel to the Beechams factory in Brentford one of the male stewards said it was a waste of time “because most of the workers there were foreign or coloured.” The following Sunday a car, carrying a black family, pulled into the picket line and the driver stepped out of the car saying:

I’m the convenor of the Brentford factory. We made a collection. I’ve come down with my family to offer support. Who can I give the money to?

He handed a bag of money over to the pickets, probably unaware that his family’s presence and solidarity had isolated and perhaps caused the evaporation of any latent racism amongst the small minority of strikers who had held such views.

The Transport union officials in Gloucester and Bristol distanced themselves from the strike. On several occasions, Brian Weston, the District Secretary had addressed mass meetings sometimes offering verbal support but on one occasion suggesting that they had been out for two weeks and made their point and perhaps ought to return to work. At the meeting, a steward read out a report in that week’s Socialist Worker and the convenor called for a vote on the return to work. The meeting, almost unanimously, voted to stay out and spread the action. “The foresters are a militant lot,” said Brian Weston, as he left the meeting… “No thanks to you,” one of the pickets fired back.

The strike lasted six weeks. During that time, many of the women strikers had spoken at meetings and events in different parts of the country, but even though money was coming in from various workplace and trade union collections, their union refused to make the strike official and refused to give the Beechams workers strike pay.

The strike was terminated by their union after someone in Coleford, who had no connection with Beechams, had organised a poll of the passing public outside the post office. The question on the poll said something like…”Do you think the Beechams workers should go back to work. Yes or No?” There was a slight majority for Yes amongst the few members of the public who had participated but it was enough for the assistant district secretary of the union, John Power, to call the strike off saying, “You’ve lost the support of the public.” The strikers went back to work.

They might not have won their wage demand, but they had demonstrated their dignity and determination. I have mentioned three women and with a better memory, I could have mentioned more. Men were involved in the strike and some took a lead role, but it was the role of the women who dispelled any myths that they were just there to support the men. They were angry fighters and they need to be recorded in history as women who were willing to stand up and fight against injustice; to stand against the rich and powerful and to challenge the union leaders who thought it more important to protect the Labour government than to support its own members.

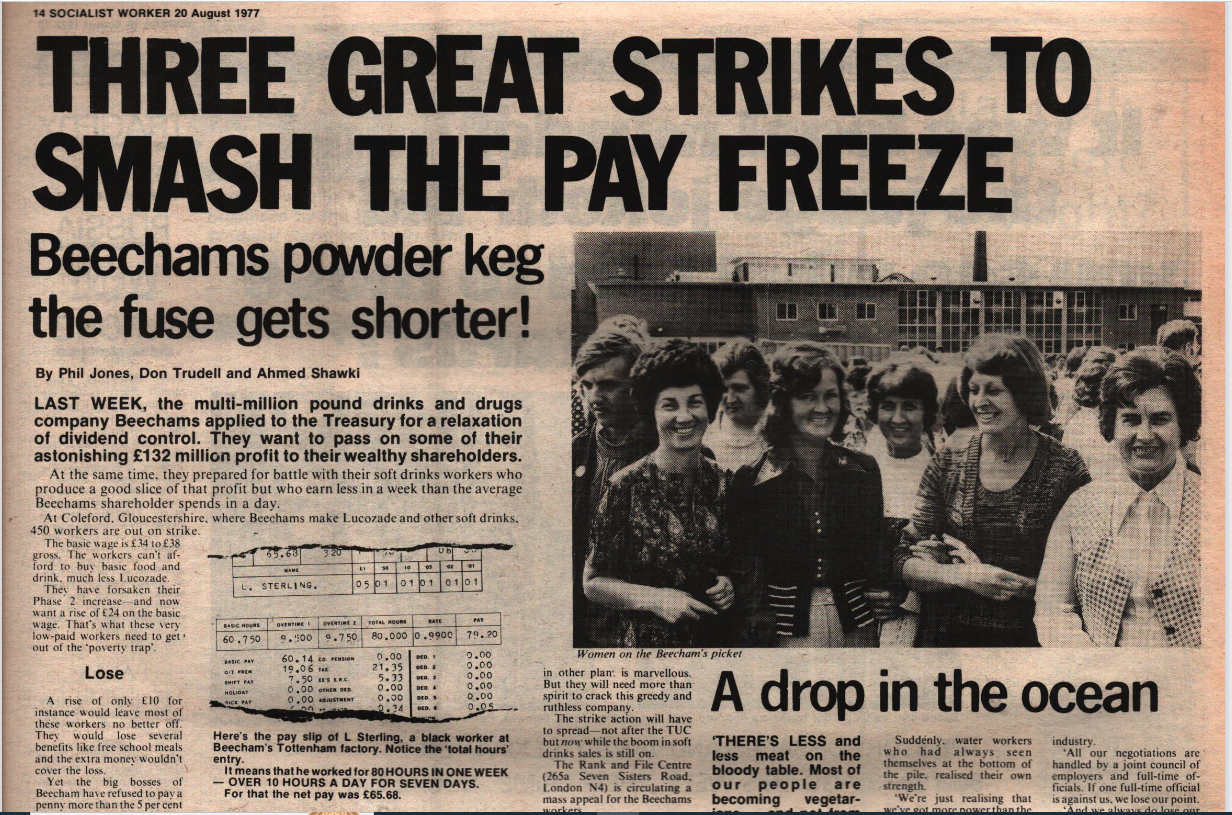

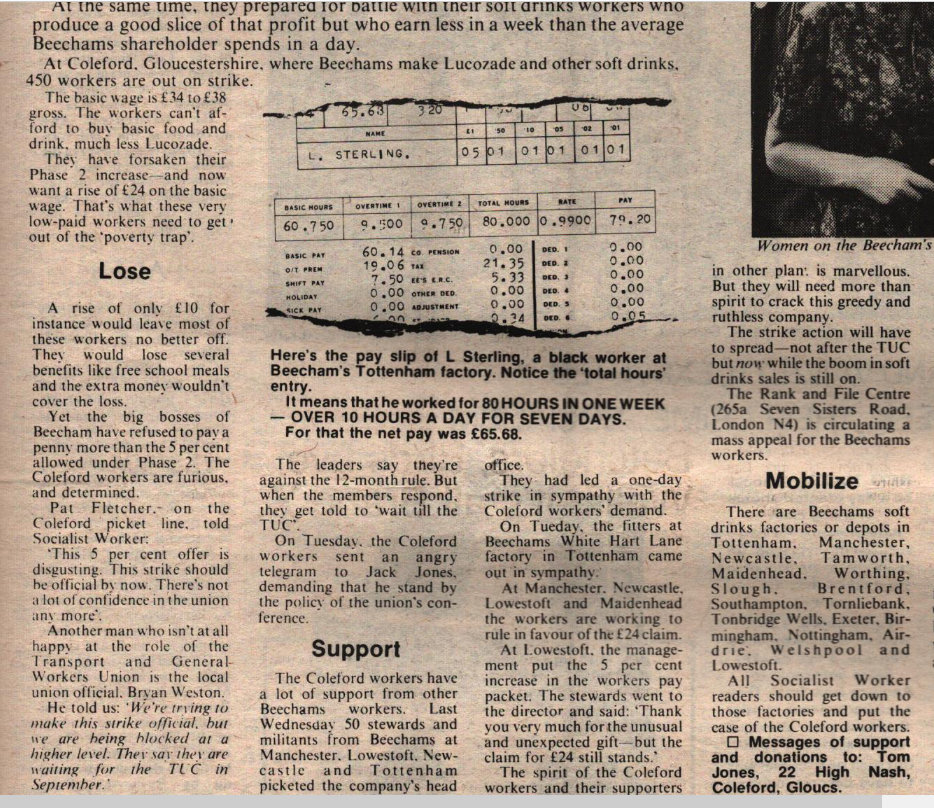

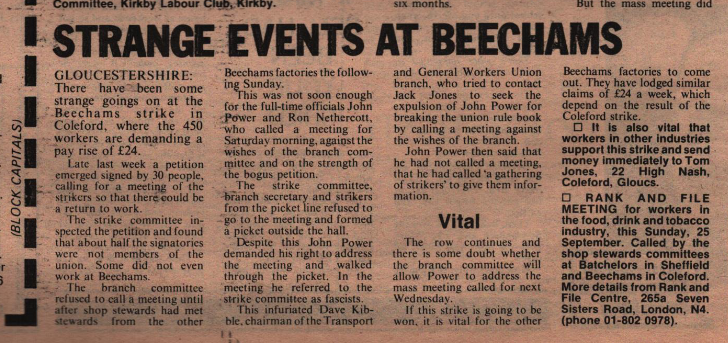

This is how the strike was reported in the newspaper Socialist Worker

2 replies on “Forest of Dean Women Take the Lead by Phil Jones”

Very interesting bit of history.

This must be the Phil Jones I worked with at Gloucester City Council in the 80’s and early 90’s

A really Good Guy to have on your side indeed.

Yep – that is him!